Menu

Engaging with Mosque Imams for Effective Responses to COVID-19

Authors’ note: The results discussed in this blog are based on a pilot. These findings are preliminary and are being presented for initial consideration and discussion. We will update this blog once information from wider research is available.

In order to combat the spread of COVID-19, a large number of Islamic countries including Saudi Arabia, Iran, Turkey, and Malaysia have put restrictions on religious congregations and gatherings, including the obligatory Friday prayer. Leading international Sunni and Shia clerics have endorsed these rulings.

And yet, in Pakistan, there has been lack of clarity on the official stance on whether and how congregational prayer is going to be restricted as part of on-going lockdowns.

Many mosques in Pakistan continue to hold congregational prayers. In some cases, this has led to clashes between the State and mosques, in which police assigned to enforce the rules on Friday prayers have had violent confrontations with large gatherings of congregants. Since restrictions were introduced, some religious leaders have publicly opposed them, and continued to organise religious events and gatherings. The situation was further complicated on 14 April when prominent religious leaders, who initially acquiesced to support the federal and provincial governments’ restrictions, announced that they no longer support them. They further added that mosques will hold all daily and Friday congregational prayers, as well as special prayers during the holy month of Ramadan which will start on 24 April. By 18 April, the Federal Government effectively agreed to lift the restrictions on congregational prayer. Leading medical doctors in Pakistan and abroad have strongly advised the government to reconsider this decision given that it would increase the risk of exposure substantially. The national conversation on this issue is still on-going and changing rapidly.

The seemingly contradictory stances of the religious leadership and the government on this sensitive issue, and the daily changes in the official guidelines, send mixed signals to the general public. This could possibly result in actions by the public that increase the risk of the virus spreading even more in the coming weeks. There is a need to reach out to the country’s religious leadership, at the national and local levels, as a partner of the government in combating the COVID-19 outbreak.

Engaging with imams of mosques

Muslims consider prayer to be one of the main religious obligations in Islam. Across the Muslim world, Muslims perform prayers five times every day; these may be prayed at home or in mosques. Muslims also perform a weekly Friday prayer, which is considered as obligatory for men to perform in congregations. All such congregational prayers involve attendants standing in rows with their shoulders touching. The attendance rates for Friday prayers at mosques tend to be higher compared to daily prayers.

The Centre for Economic Research in Pakistan is conducting a study to test whether outreach with local religious leaders, specifically mosque imams (those who lead prayers at mosques), can enhance state effectiveness in dealing with the COVID-19 crisis. Communities consider imams as trusted sources of guidance on religious and social matters. We are reaching out to imams in the province of Punjab to learn about their response to and compliance with the government’s restrictions on Friday prayer. We are also gauging their knowledge about the spread of the disease and the government’s economic support programmes targeting the poor that have been impacted by the outbreak.

In the on-going study, we hope to contact thousands of imams across Punjab, sharing information about public health and decrees from leading international clerics supporting measures against COVID-19.

Findings from initial engagement

The preliminary findings from our pilot survey of over 100 imams in Punjab, conducted in 2020 from 31 March to 14 April, are as follows. This was the timeframe in which the government’s orders were to suspend congregational prayers.

Steps taken to tackle the spread of COVID-19

There is some degree of conflict between the stances taken by most of the ulema and the provincial and federal governments regarding the status of congregational prayers. We think that this conflict plays out in the results as well.

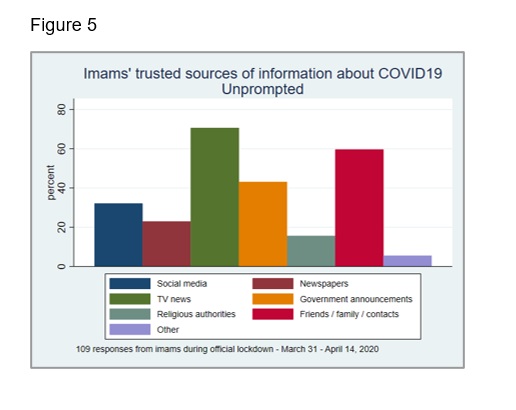

Despite the lockdown and orders from the government to suspend congregational prayers, approximately 47% of the imams who responded to the survey reporting holding congregational Friday prayers the week before (Figure 1). So far, compliance with the government regulations seems to be better for rural areas as a higher percentage of imams of rural mosques reported suspending Friday prayers (Figure 2). For mosques that did hold Friday prayers, the average turnout was much lower than a typical Friday prayer at that mosque (Figure 3).

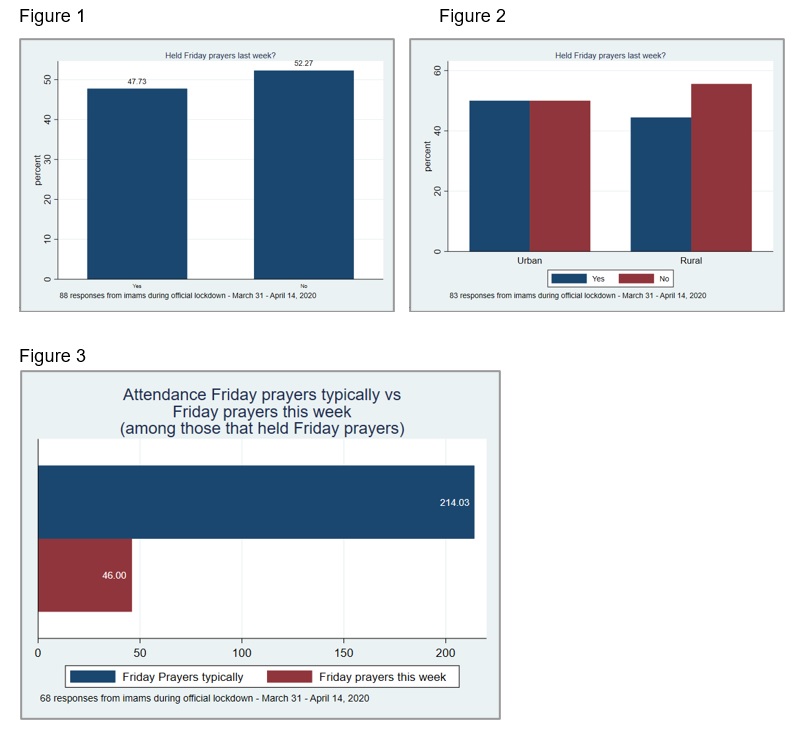

Many imams were keeping their mosques open, but reported taking at least some steps to prevent the spread of the virus. However, most of these were restricted to cleaning the mosque or removing communal prayer mats (Figure 4). Only about 40% of the imams mentioned that they either encouraged congregants to distance themselves from each other and a similar percentage discouraged handshaking or hugs among congregants. After these results came in, the government and ulema announced a compromise of keeping mosques open, but with social distancing and hygiene measures as well as restrictions on attendance by the elderly. Medical groups announced opposition to this plan, in part because these measures may be insufficient and impractical to enforce. We will continue to gather data to find out how well these measures are being followed.

Sources of information

Sources of information

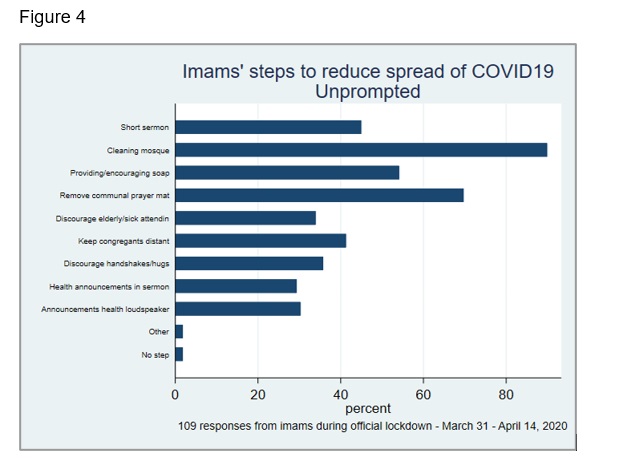

The results show that imams mostly trust TV shows and their social networks for information on COVID-19 (Figure 5). Mainstream TV networks discuss the steps taken by the government to prevent the spread of the virus, steps taken by other Muslim countries (like cancelling congregational prayers), and the stance taken by local religious leaders/ulema.

In light of the conflict and confusion over rules that are being renegotiated every day, it is not clear what role the media and TV shows play in informing the views of imams. We can explore the kind of media that is consumed by imams and the messaging on such media platforms. Using these initial results, we plan to delve deeper into the role of media in informing the views of imams. This will enable us to suggest policy interventions on how talk shows and other forms of media can play a constructive role through their messaging.

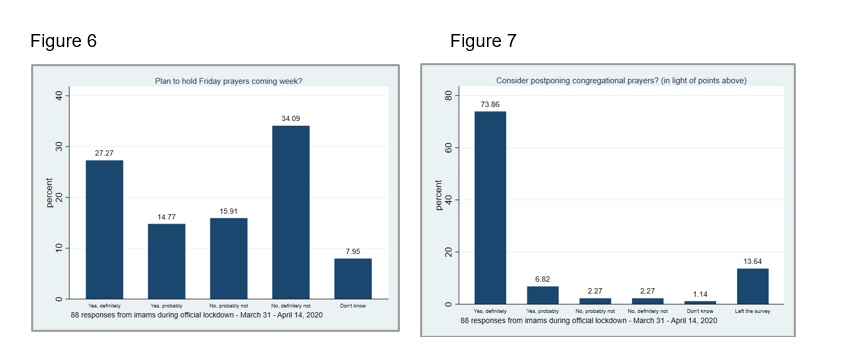

Imams are receptive to information

On the whole, the imams seemed to be receptive to information about government rules and statements by religious authorities provided through the survey. While only 50% of the imams said that they planned to cancel Friday prayers at the start of the survey (Figure 6), by the end of the survey around 80% of the imams mentioned that they were considering postponing congregational prayers in light of the information provided during the survey (Figure 7). However, we would view these numbers with caution as imams might simply state agreement to say what surveyors expected to hear. Going forward, we will collect follow-up information from imams and others in their areas on actual congregational prayers and closures.

We expected community imams to push back against the government suspension of congregational prayers, as some national religious leaders have done. However, during the period when the suspension was in place, community imams we called were receptive to the information, not defiant. This suggests that there is room for meaningful discussion and change regarding the status of congregational prayers. However, once the government revised its position in the last few days did respondents start to indicate more disagreement. This suggests that the combination of leadership from government as well as religious legitimacy (from the fatwas issued by international religious authorities) might be important for convincing imams to take steps to protect their congregation through social distancing.

Leveraging imams for spreading information about relief programmes

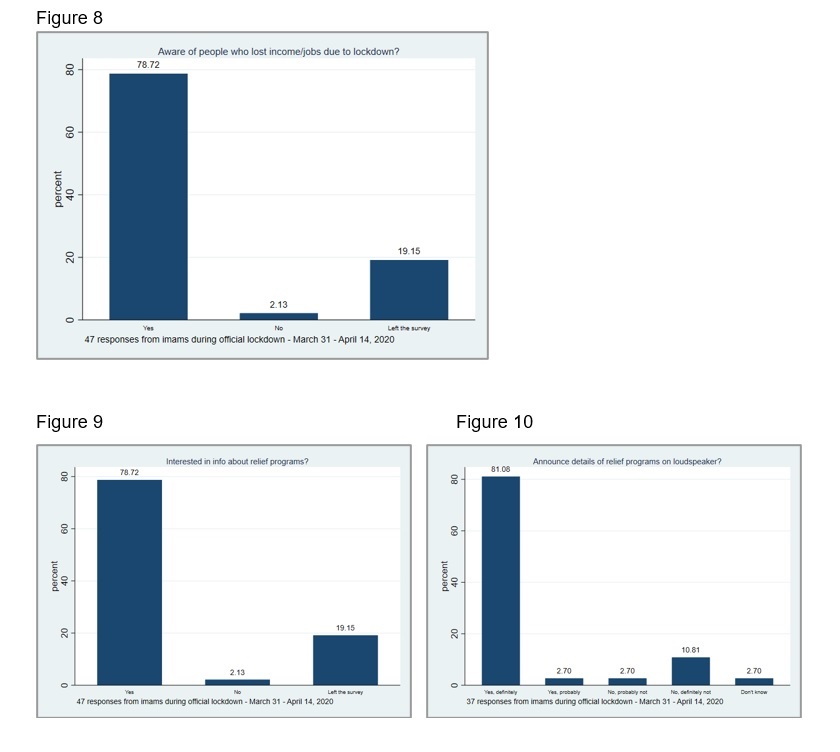

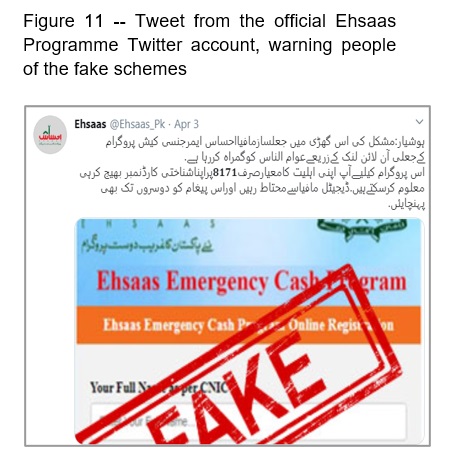

As imams are considered respected sources of information in the community, they can also act as a means of disseminating trusted information about various assistance programmes that have been launched by federal and provincial governments. In the survey, imams were provided with verified information on the various relief programmes and encouraged to disseminate this information through their mosque’s loudspeaker and to deserving families. Not only are imams aware of families that have faced economic hardship due to lockdown (Figure 8), they are also interested in the information (Figure 9) and willing to announce this information through their mosque’s loudspeaker (Figure 10). This dissemination of information could help ensure that all eligible households learn how to access the programmes, as well as combat the spread of fake information regarding them (Figure 11).

Generating evidence for policymaking on COVID-19 and beyond

We plan to scale up outreach with imams to spread information and quantify the impact of this kind of outreach. In the short-term, we aim for the results of the research to be useful in guiding government agencies in effective community outreach to address the spread of the disease, as well as mitigate the adverse economic impacts. If the results in the coming weeks suggest the engagement had a positive impact, we will actively reach out to the health department and other relevant departments to propose they consider scaling up this kind of outreach through mass media. As mentioned, 70% of imams cited TV programmes as their source of information. As a next step in the study, we will gather data on the specific TV programmes they watch and find credible ways to help inform rapid policy guidance on the most effective channels of outreach.

In the longer term, we hope our research will help us understand how states can best work with traditional authorities such as religious leaders. This will improve the effective response of states in both emergency and non-emergency situations, such as addressing misinformation on issues of law or public health, and improving take-up of government benefits among unreached groups.