Menu

Resolving Pakistan’s Economic Woes – Weighing our Options

Well into its second ever democratic transfer of power, and facing a looming balance of payments crisis just two years after the completion of a USD 6.6 billion IMF program, it is still uncertain whether Pakistan will seek another IMF loan to meet high-pressure external financing needs. The Economic Advisory Council suggested last week that the government must be prepared to take some tough economic decisions. It is not clear if these decisions include opting for another bailout. Given the health of the external sector, several experts believe that not going to the IMF may be far more economically and politically riskier than any alternative. The range of other options available will each have to be timed, pursued and implemented immaculately to cover the financing gap – a move which may not be realistic even if is probable.

The Economic landscape – The facts

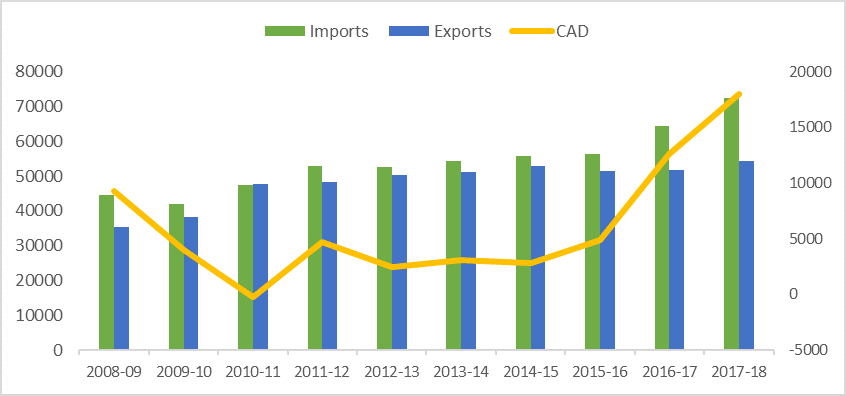

The on-going balance of payments crisis has its roots in the current account deficit that quadrupled in the past two years touching USD 18 billion by the end FY18, up by 42.5 percent over the previous fiscal year. The State Bank of Pakistan has just around USD 10 billion worth of foreign exchange reserves – barely enough to fund imports for more than two months. Pakistan’s overall trade deficit in FY18 stood at USD 37.7 billion with imports standing at a record USD 60.9 billion. Government’s budget deficit is also well over 7 percent of its GDP. Foreign direct investment has only marginally improved since FY15, when it hit a record low. Pakistan will not be able to sustain its current growth at 5.8 percent for much longer.

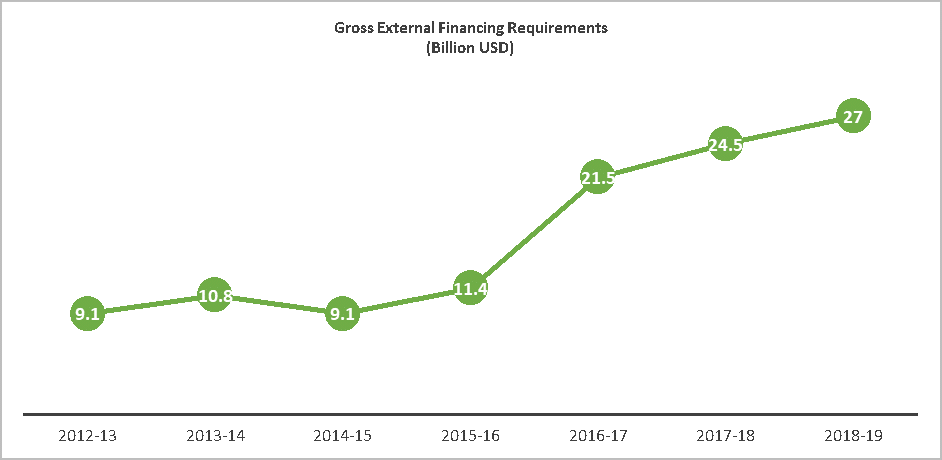

Senior economists have estimated an external financing requirement of 26 bn for Pakistan which compares well with the IMF estimates of USD 27 bn and the Ministry of Finance’s calculation of USD 23 bn. According to a report by the interim Finance Minister, Pakistan would require USD 9.3 bn to meet its debt-related obligations in FY19 that includes repayments to the IMF[1].

Understanding the causes

The fiscal irresponsibility demonstrated by the previous government must be understood and acknowledged as a major contributor to Pakistan’s current financial crisis. To state simply, the government spent more than it collected. It incurred enormous expenditures in the form of large investments in infrastructure, energy, CPEC-related projects without increasing the revenue inflow. Secondly, it continued to import far more than it exported while export-led industrialization was pushed to the back-burner.

When governments are faced with a fiscal crisis they usually have three main levers to push the economy back on its feet. The first is to devalue the currency as an effective fall in the exchange rates can help the economy become more competitive. The State Bank has already devalued the rupee four times since December 2017 thus further devaluation may not be an option.

The second option is to curtail public expenditure under a tight fiscal policy. With a limited fiscal space, this can be done by managing demand – placing cuts in development spending, placing more taxes and reducing reliance on imports. Regardless of an IMF bailout, Pakistan will seriously need to slash down government expenditure.

The third option is to draw on temporary funds to help address immediate liquidity shortages and financing gaps. This is usually a last resort and works best as a means to give the country more time to deal with the deficit while making room for it to address the structural deficiencies. In the case of Pakistan, this option would most likely manifest itself as yet another IMF loan.

What will an IMF bailout look like?

Although IMF has not made any promise to bail out Pakistan, nor has Pakistan formally asked for one, the finance minister has clearly stated that if Pakistan does decide to go to the IMF, it will not be the first but the thirteenth time it will be doing so[2]. Experts anticipate a final word on it by end of this year. Pakistan may seek USD 10 to 15 billion in what could be its largest IMF package till date[3].

An adverse reaction from the US, IMF’s biggest shareholder, can complicate and extend negotiations. The US has clearly urged IMF not to promise any funding to Pakistan until it publishes full details of the loans it has taken from China to pay for CPEC. Currently the net transfers (i.e. disbursement minus debt-servicing) from China are positive. Re-payments don’t feature in the current financing gap. Thus the fear that IMF support will be used to bail out Chinese bondholders is unfounded.

Any successful IMF program requires government’s commitment to the policies outlined in the program. While the IMF is unlikely to refuse funding to any country its assistance will come with the standard neoliberal policy conditions that will include further devaluation of the rupee, privatisation of loss-making state owned enterprises, a rise in power tariffs and reduction in subsidies on agriculture. Associated with a new potential loan will also be extensive pressure to reduce aggregate demand of which the largest burden will be on the fiscal side. This will be critical for reducing the deficit from 7 to 5 percent of the GDP in the first year.

This could hamper Khan’s efforts to substantially enhance public spending and also hit economic growth. The last time Pakistan entered the IMF program, growth rate stood at under four percent. This poses a challenge to the new government, voted in with high expectations to set up an Islamic welfare state. As part of PTI’s 100-day agenda, its electorate will expect initiatives for social uplift and job creation. The PTI has promised to create 10 million jobs and build five million low-cost housing units in the next five years.

Exploring alternatives

While steps have been taken, such as multiple currency adjustments, to address economic imbalances, avoiding an imminent default on international payments requires much more. Going to the IMF will most likely lead to the imposition of inflexible and untimely policies for the new government, thus it is actively considering several alternatives. However, none of these options are sufficient to meet the financing needs on their own.

Government is considering placing regulatory duty on or curtailing certain imports to reduce the financing gap. However only imports from formal channels can be taxed. Most luxury goods are under-invoiced or smuggled so unless their true value is declared the benefits of such a scheme will be limited and this may encourage further under-invoicing.

Relying on the goodwill of some countries – Saudi Arabia’s help in deferring oil payments and rescheduling of some of the repayments under CPEC – can ease off some of the pressure. Other fiscal measures to reduce public expenditure, manage demand and control capital may help.

Government also plans to launch investment (Sukuk) bonds for overseas Pakistanis. This would be similar to the Central Directorate of National Savings (CDNS) – a dollar-denominated bond. However, borrowing from the capital market may be restricted following Pakistan’s altered credit ratings from stable to negative.

The government has also promised a massive privatisation drive by making a special wealth fund where all SOEs will be transferred to obtain necessary funds that may help with IMF negotiations for a more favourable deal.

Possibility of bilateral financial assistance also expands Pakistan’s menu of choices. China has assured Pakistan it can be counted on and its funding would not come with IMF-like conditions. However, Pakistan is becoming increasingly dependent on external financing from China’s state-backed banks since the last financial year, having secured loans worth more than USD 5 billion. It already lent Pakistan USD 2 billion in June this year – just ahead of the elections to boost its foreign reserves, and further loans from China will significantly add to a higher debt burden. In early August, Saudi-backed Islamic Development Bank (IDB) also agreed in principle to lend Pakistan more than USD 4 bn. Borrowing from friendly countries provides a low quantum at a much higher interest compared to IMF.

Sustaining growth – a long-term view

Whether we seek another IMF loan or not, the critical question to ask is if our government has a home-grown plan to make the economy stand on its own feet. A bailout will only provide breathing space and postpone the current fiscal crisis. Policymakers will have to take concrete measures to address the underlying causes of macroeconomic crises that repeats itself every few years.

The fundamental imbalances stem from a disparity between public sector spending and income, and an underdeveloped export base. An IMF loan will not address these structural shortcomings nor will it re-distribute the means of production to fix this. The sooner this is realised the better it will be for generating a plan for stable, inclusive and sustainable economic growth.

At the same time the government should also think through the design and associated conditionality of any stabilisation program. The conditions should not only be realistic but also speak to the structural deficiencies. Revenue inflow must be expanded by enhancing the tax base rather than tax rates. Subsidies should be targeted instead of being removed altogether. Privatisation of state-run-enterprises while necessary should be planned with a longer time horizon. At the same time a fundamental revisiting of the public policy and business environment is needed to encourage exports. Reforms also need to be introduced to leverage the potential of its youth and the private sector. Any further stalemate in policy direction to address these structural concerns will only lead to more macroeconomic instability in the future.

Hina Shaikh is the Country Economist at the International Growth Centre (IGC).

[1] “Stabilisation and economic growth policy recommendation paper”, prepared by the former interim finance minister Dr Shamshad Akhtar-led finance ministry.

[2] Technically it would be the seventh time excluding individual loans that were often combined or led to larger programme loans.

[3] 7.6 billion in 2008 is the largest IMF bailout package