Menu

Political Economy of the Durand Line: Ramifications for Pakistan, Afghanistan and Regional Security

Introduction

There are two dominant schools of thought on the Taliban attempts at de-fencing the Durand line; the first regards the attempts as being state sponsored and taking place under the patronage of the Taliban government, the second suggests that the Taliban government is not fully representative of all Taliban factions some of whom have become recluse and their border activity stems from the opposition of the advances that the Taliban in Kabul are making towards Pakistan. There is a third school of thought too, slightly more nuanced but maybe less mainstreamed. Those belonging to this school think that since militancy has become the natural order in Afghanistan, forces de-fencing the border are neither backed by the government nor do they belong to a group with any political interest linked to the government in Kabul and Pakistan. They are hostile groups who will fight against forces on both sides of the border and need to be combated jointly by responsible governments in the two countries.

However, if one looks at how the economics in the region is shaping up, groups that are dismantling Afghanistan’s developing ties with Pakistan must be tackled by the government in Kabul even before they are dealt with by Pakistan. The simple reason for Kabul to do so is the great amount of economic dependence that a food-starved and macroeconomically unstable Afghanistan has on Pakistan. With India now gradually detaching itself from the security and economic affairs of Afghanistan, the latter has come to depend ever so greatly on Pakistan and its all-weather ally; China. Events like the breaches of the Durand line will only serve to frustrate a currently benevolent Pakistan that is committing to play its role in rebuilding the war-torn Afghanistan. Pakistan must therefore assess the situation in Afghanistan more carefully and understand the transition that is taking place to know exactly which stakeholders it wants to engage with and how does it strike the right balance between ensuring border controls while rebuilding its fractured relations with Afghanistan in the aftermath of the American exit.

Pakistan During the Afghan War

Barring a few decades between 1920 and 1970, the Durand line has continued to be a porous border. Pakistan’s idea of keeping the border porous in the past is largely rooted in the history of the Afghan war and Pakistan’s strategic decision to support the Afghan forces in their attempts to thwart Soviet invasion of their territory, part of which was rehabilitating the afghan refugees entering Pakistan. Fearing a potential spillover of the afghan war to its sovereign territory, Pakistan became a natural ally of the US and the mujahideen in thwarting the rapid onslaught of the Soviet forces. The military school of thought in Pakistan believed that the Soviets are entering the region with an intent to militarily dominate Pakistan while the ‘mullahs’ saw it as a communist attempt to silence a resurging Islam. In either case, the mainstreaming of the pre-emption of a Soviet insurgency in Pakistan created political legitimacy for the armed forces to enter the war and draw upon massive levels of public support. The war meant that not only was Pakistan fighting alongside the mujahideen, but it also permitted the use of its northern frontier as a strategic territorial buffer for the mujahideen. This meant maintaining the historic porosity of the Durand line, and its violations continued through the decade of the 1980s. The historic progression of events surrounding the Durand line and the trajectory of the highs and lows of its international recognition and legitimacy between the fall of the USSR and the withdrawal of the American forces in 2021 is by all means indicative of the fact that Pakistan has a heightened border conflict on its hands and reasserting the sanctity of the Durand line will be more troublesome than it was during the last two decades of American presence in the region when a large burden of keep a check on illegal immigration and ensuring security on both sides of the Durand line was shared by the US / NATO forces. The more troublesome this conflict will be for Pakistan; the greater will be the economic costs that Afghanistan will bear as a result of severing ties with Pakistan.

During the war on terror, arguments were advanced by the Afghanistan, Pakistan intelligentsia in favor of the porosity of the Durand line. In fact, with the rise of the TTP, border controls had become impossible to enforce and maintain during the war. Experts in the region suggest that porosity was not a necessity for Pakistan, but a compulsion tightly enforced by the Taliban and in some cases by the American and NATO forces. Regardless, with the end of the war in 2021, Pakistan has every reason to bring in more rigid border control measures to protects its territory against an expected refugee explosion. There is no common enemy or a preemptive threat of use of force by a global superpower like the USSR, neither is there any financial or economic incentive to rehabilitate afghans displaced by the war. The counter-factual in this case thus is much stronger that the rational response for Pakistan is to restore the sanctity of the Durand line which was duly legitimized as an international border by the Anglo-Afghan treaty of 1919.

Current Situation along the Durand Line:

During the last year, border forces in Pakistan blocked several Afghan attempts to tear through the ‘fencing of the Durand line’ which Pakistan completed over the last few years. While Pakistan’s outgoing National Security Adviser, Moeed Yusuf who made a diplomatic visit to Afghanistan in January 2022, reassured that the afghans are receptive to the idea of resuming dialogue with Pakistan including on the issue of the Durand line and forthcoming in their approach towards sustainable peace in the region. The continuing Afghan attempts to violate the sanctity of the border are irritants that will only push Pakistan away from the government in Kabul and enhance security along border which will have serious economic repercussions for Afghanistan. In particular, the defencing attempts will:

- intensify matters within the Taliban factions some of whom are keener to take a more congenial approach to Pakistan and see Pakistan as more of a benefactor than a cause of their failures of the past;

- push Pakistan’s strategic move of mobilizing its diplomatic and political resources within Afghanistan and make a selective strengthening of its ties with forces that can advance and protect its interests within Afghanistan; and

- have severe economic-cost implications for Afghanistan especially vis-à-vis the food security crisis, the mitigation of which depends enormously on the transit food imports from Pakistan many of whom are registered under the Afghan-Pakistan transit trade Agreement (APTTA). According to 2014 data by the Asia Foundation, Pakistan is the largest destination for afghan exports (33% of all exports) and the second largest for afghan imports (17% of all imports). On the other hand, Afghanistan is a much less significant trading partner for Pakistan; source of no imports of any note and less than 7% of exports. Trading-off food and larger economic security for a border conflict that hasn’t borne any substantial political or social outcomes for more than a century seems like a bad choice for Afghanistan, but whether this realization prevails within the governing Taliban ranks is both critical and interesting.

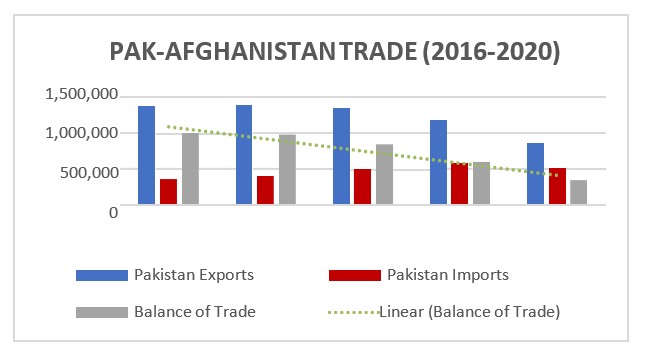

The table below shows how trade between the two countries has continued to fall in the years directly preceding the American exit from Afghanistan (2021). It is interesting to note that the balance of trade was shifting in favor of Afghanistan since 2016. Pakistan’s imports had been rising since 2015 after which they experienced a slight fall in 2016. Pakistan’s exports from Afghanistan had remained largely stagnant between 2016 and 2018 but began to fall in 2019 experiencing a significant year over year decline in 2020.

Table.1: Pak-Afghan Trade Balance (2016-2020)

The trade balance shift towards Afghanistan in the run-up to the American exit reinforces why the economic cost of broaching the Durand line subject will be costly for Afghanistan which was seeing Pakistan develop as a profitable trading partner. Pakistan has a more diversified trading ecosystem, both in terms of product diversification and number of trading partners and thus the closure of trade ties which could result from an intensified conflict over the Durand line will make Afghanistan vulnerable from a food security perspective and create external account imbalances that will jeopardize the country’s macroeconomic stability, especially in the backdrop of $7bn of frozen foreign exchange accounts by the US.

Why Pakistan Must Improve Border Security?

There are three reasons why Pakistan needs to, and will secure the fencing of the Durand line: every new government in Pakistan has more pressure from the public to block the inflow of afghan refugees from the north, two, opposition parties have been using the Durand line as an excuse to blame successive governments for not being able to protect Pakistan’s territorial sovereignty and, three, the porosity of the Durand line is now seen as the cause of the rise of TTP in Pakistan and suicide bombings most of which have been attributed to the afghan refugees that entered Pakistan because of the porosity of the Durand line.

The breaches of the Durand line also threaten to undermine Pakistan’s present policy towards the Taliban government in Kabul. Pakistan must preserve the sanctity of the Durand line in order to maintain national security and manage refugee flow. It wants to see a stable and prosperous Afghanistan but clearly not one that becomes strong enough to bully Pakistan but likely to be one whose crises don’t seem to create a regional problem that transcends borders. But what Pakistan doesn’t want is to host more afghan refugees, many of whom have been vulnerable to recruitment by banned terrorist outfits. UNHCR reports that Pakistan currently hosts 1.4 million refugees down from a peak of around 3 million refugees that crossed the border during the afghan war in the 1980s. FATA, the region that hosts the north and south Waziristan agencies, the home of Pakistan military’s operations to oust the TTP, were merged within the province of KP in 2019.

While governance problems regarding the sharing of resources between the former KP and FATA continue, FATA has become a more protected and barricaded territory after the merger. And in all certainty, efforts to breach its borders to enter Pakistan would see a stronger retaliation from Pakistan than at any time between 2001 until the merger in 2019. Clearly, the region is on the brink and any disruptions in the current state of affairs, even if for an age-old conflict like the Durand line could mean a potential tip-over in the wrong direction and that the food security and refugee crises in Afghanistan are not met with a supportive and friendly Pakistan and become a permanent malady for Afghanistan and the region.

Policy Implications and Conclusion

As the security situation continues to devolve in Afghanistan and while it will risk the lives and livelihoods of the 40 million Afghanis, the crisis could re-enter Pakistan and maybe with a much stronger force than it was during the American presence in the region. Therefore, Pakistan must be cautious in making its diplomatic moves around the Durand line conflict. It cannot allow Durand line to be de-fenced while at the same time it cannot use force in dealing with groups attempting to make breaches to cross the border. Both approaches are likely to intensify matters on the border and take the situation out of the hands of the two governments. As I have stated before, Pakistan must identify stakeholders it wants to engage with in Afghanistan and make them understand that the costs of defencing the Durand line will be much greater for Afghanistan than they will be for Pakistan.

Afghan forces must continue to develop stronger ties with Pakistan and China and ensure that they are sensitive to India-Pakistan dynamic in the region. It is not a region where any state can claim friendly relations with all regional countries. With the rising polarization in South Asia, it will be better for Afghanistan to pick sides which will be vital for its economic sustainability. Durand line is an age-old conflict and the minor breaches that the groups are making to the Pakistan’s fencing attempts might be costly for Afghanistan. If the de-fencing activity is sponsored by the state, it must rethink its strategy of doing so since a potentially unyielding strategic move would cost Afghanistan the trade routes that are critical for its food security needs.

Afghan forces should investigate their ranks to identify and crackdown on forces that are attempting to disrupt peace in the region and dismantling their developing ties with Pakistan. Both sides need to send the right signals and compound confidence building activities to ensure that they can bury the hatchet and move forward. If these moves are not state sponsored, the government in Kabul must come out openly against groups attempting to de-fence as to give an open message to the government in Islamabad of its opposition of the breaches of the Durand line.

Asad Ejaz Butt is a public policy professional trained in Economics and International Development Studies with over 10 years’ experience in areas of public financial management reforms and macro-fiscal policies and regulations. He has written quite extensively on the political economy of trade and institutions in South Asia, focusing specifically on documenting the Afghan economy.