Menu

COVID-19: Pakistan’s Preparations and Response

The government of Pakistan has taken unprecedented steps to counter the effects of the COVID-19 crisis, but it is unclear if these will be enough given the challenges facing the country prior to the pandemic.

Pakistan is amongst the 180+ countries dealing with the coronavirus pandemic. There are now clear warnings of a global economic recession as workers continue to fall sick, factories remain shut, and healthcare systems become overwhelmed. Mitigating the health emergency and extent of economic loss will not be easy for Pakistan. The country of over 200 million is already going through a macroeconomic stabilisation, and ranks below world average on most human development indicators.

The spread of disease within and into Pakistan cannot be separated from the global context. The world’s urban population at 4.2 billion has now exceeded the global rural population, and almost 40% of Pakistanis live in cities. Meanwhile in the country, close to seven million use air transport.

COVID-19 has already surpassed the death toll of the more recent outbreaks of Ebola, MERS and SARS. While fatalities in Pakistan have as of 17 April hit 130, it has more than 7000 confirmed cases, and many more can be unreported. Half of these cases are now locally transmitted. Government estimates suggest by the beginning of June cases in Pakistan could rise to 58,000, while mortalities could lie anywhere between 5 to 10%

of this number. In all eventuality, Pakistan’s healthcare system is likely to be overwhelmed.

At the moment, it is hard to calculate and forecast the true impact of coronavirus beyond the estimated human toll. The outbreak is on-going, and researchers are continuing to learn about this new form of virus. While the SARS outbreak cost the world $50 billion, initial estimates for coronavirus are already suggesting a loss of $360 billion. In Pakistan, relatively localised epidemics (such as Dengue, measles and Hepatitis C) have posed challenges. A full-fledged global pandemic can have dire implications.

A fractured health system

Outbreaks of such scale expose gaps and fractures in the underlying healthcare system. This can be related to the timely detection of disease, availability of basic healthcare, tracing contacts, quarantine and isolation procedures, and preparedness beyond the health sector. All of these issues are especially prominent in resource-constrained settings.

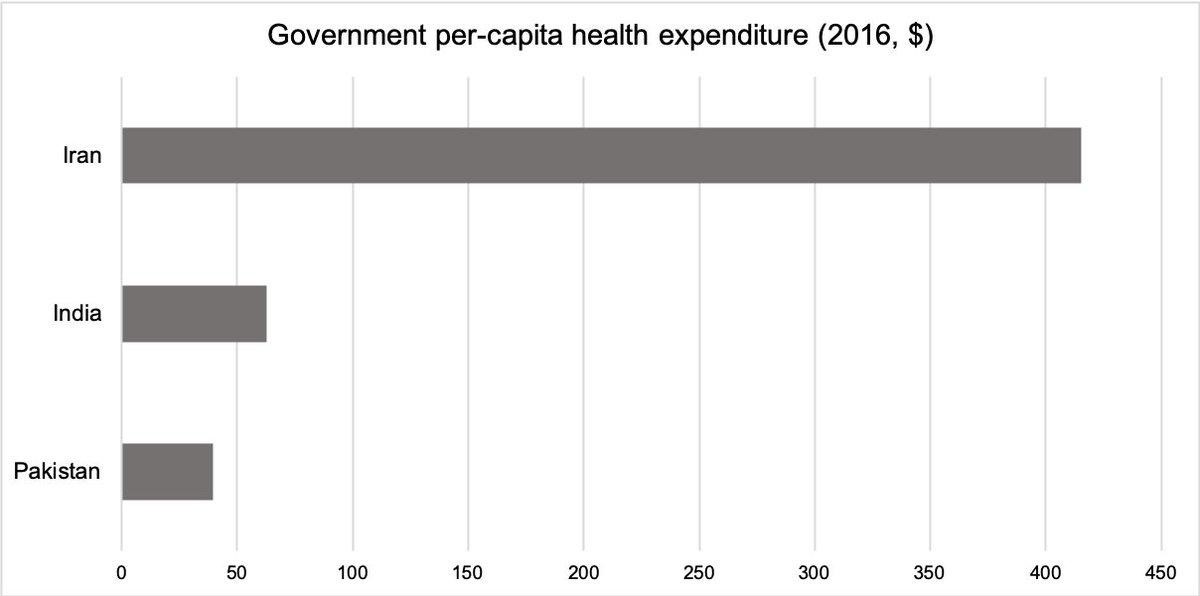

Pakistan spends 2% of its GDP on healthcare, against a global average of 10%. It also fares much worse than its neighbours, Iran and India, in terms of health-related indicators. Latest data from the World Bank, presented in figure 1 below, show that in 2016 Pakistan spent around $40 per citizen on healthcare. By contrast, the comparative figure in India was $62, and Iran $415. With the growing crisis in Iran despite this higher spending on healthcare per capita, it is clear why policymakers in Pakistan are deeply concerned.

Figure 1

Source: World Bank

Some feel that Pakistan focuses on public health preparedness only sporadically, mainly as a reaction to episodes when vulnerabilities spike. The country therefore lacks a health system that can scale up both detection and treatment to adequately and timely address large-scale outbreaks.

Moreover, disease prevention is not just about a sound health system, but also concerns confronting factors that create conditions for poor health outcomes. For example, certain segments of the population (such as the poor or those with underlying health issues) remain disproportionately at risk of the disease. Low income is associated with higher rates of chronic health conditions such as diabetes and heart disease, and lower uptake of precautionary health measures.

Unequal access to healthcare combined with a lack of social protection

Unequal access to healthcare is a problem for everyone, since this disease does not differentiate between the rich and poor. Yet the poor are far less resilient than the rich in having tools such as access to private health care, better education, option to work from home, and access to insurance to lessen the shock of such outbreaks. In fact, this particular coronavirus can be up to 10 times more deadly for the poor.

The need for social protection is also almost always accentuated during an emergency. In Pakistan, social protection expenditure is just under 2% of GDP, far lower than the global average of 11.6%. Most of the informal sector is not covered by such schemes despite its contribution to the GDP (almost one-third) and employment (72% of all jobs outside agriculture). The Pakistani equivalent of a public distribution system, the Utility Stores Corporation, is grossly underfunded and unlikely to plug gaps if food supply chains are disrupted.

Dealing with resistance

The Government of Pakistan is particularly hampered in its ability to deal with COVID-19 by the social, political and cultural context of the country. Resistance created by community dynamics, local/religious beliefs, political instability, economic fragilities, and a lack of trust in government and institutions, has made Pakistan struggle with far less infectious diseases like polio. The fight against Ebola in Africa was subjected to similar challenges. Pakistan is now facing the same obstacles with coronavirus.

To counter this, mosques have been shut down in most Muslim nations including Saudi Arabia. However, Pakistani policymakers have not adopted such stringent measures for fear of a backlash from the religious wing. They have so far only restrained congregational prayers on Fridays. It is nonetheless important to explore ways of working with religious organisations and leaders to influence outcomes and behaviour.

Cooperation between different levels of government

On top of the challenge from religious institutions, within the government there are cooperation obstacles that must be overcome. There is a lack of coordination between the federal and provincial governments. Well-coordinated governance structures are critical for a quick and efficient response to such a crisis. As most critical services including health and social protection are now the responsibility of the provinces, each province is making decisions independently. However, border control and aviation remain with the federal government and provinces lack jurisdiction to tighten surveillance at airports.

Moreover, for countries as populated as Pakistan, local governments can play a pivotal role in reducing disease transmission and resistance to health providers by leveraging local networks. An absence of local governments has meant a delay in reaching communities to offer both healthcare and relief.

A major economic downturn

The economic ramifications of the crisis are also significant in Pakistan. A downturn in Pakistan’s GDP growth was anticipated even before the epidemic reached the country. The State Bank had already revised downwards the GDP growth rate to 3% from an earlier estimate of 3.5% for the 2020 fiscal year. The Asian Development Bank also lowered its projected growth rate to 2.6% from an estimated 2.9% while the World Bank has revised it downward to 1.1% and in the worst case scenario a negative 2.2%. Official assessments estimate an initial loss of PKR 2.5 trillion (around $15 billion)

It has further forecasted an economic loss of up to $5 billion, while official authorities expect anywhere between 12.3 to 18.5 million layoffs.

How is Pakistan responding?

The government of Pakistan has unveiled a PKR 1.13 trillion ($6.76 billion) rescue and stimulus package with a good balance between providing direct assistance to the vulnerable and protecting industry and businesses. The allocation is sizable but its true impact can only be assessed by how it is implemented. Some of this will be funded by support from the World Bank and Asian Development Bank coming in over the next few months.

Like many other countries, the government is experimenting with various forms of a lockdown. Sindh was the first province to implement a curfew-like lockdown. Karachi faces the most stringent measures compared to anywhere else in the country. Meanwhile, Punjab has implemented a milder form of the lockdown and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) a partial lockdown. The Prime Minister, Imran Khan, has been adamant against a complete nation-wide lockdown, stating Pakistan’s inability to handle its far-reaching economic ramifications.

Direct investments into healthcare infrastructure and services have also been undertaken. Currently, only half the 2,200 ventilators in Pakistan are functional to treat coronavirus patients. An amount of PKR 50 billion ($298.94 million) has been set aside to purchase medical equipment. Pakistan’s testing capacity has also been enhanced from 30,000 to 280,000 and according to official sources will be further enhanced to 900,000 within April.

The federal government has set up a Command and Control Centre for Coronavirus (COVID-19) to have a centralized mechanism for sharing information, updates, figures and directions on disease prevention and is gearing up to provide protective gear to frontline workers.

Using technology to create awareness

Pakistan is coming up with innovative smart solutions and exploring the use of technology to create awareness, mitigate the risks, and contain the shock created by such pandemics. To promote public knowledge, the government has, in collaboration with the telecommunication industry, replaced ringtones with an awareness message to the caller about the dangers of Covid-19 and measures that can be taken to remain safe. The government regularly sends an SMS to encourage people to wash hands and practice social distancing. Authorities are also contacting suspects of confirmed cases through mobile tracking and pushing them to get their tests done.

Ensuring food security

Of course, ensuring food security and access to a safety net are just as critical as having a sound health system. The government plans to temporarily abolish all taxes on food items and has announced a significant reduction in oil prices. Payment of utility bills has been deferred for three months for households with bills falling below a certain threshold. A sum of PKR 50 billion ($298.94 million) has been earmarked for government-run utility stores to ensure the constant availability of food and other necessities. PKR 280 billion ($1.68 billion) has been allocated to ensure wheat farmers do not face cash flows and to smooth wheat procurement. The government has also kept funds for logistical support to the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), the federal authority mandated to deal with a wide spectrum of disasters, to ensure food supplies.

Furthermore, cash transfers are being leveraged in the country. In fact, Pakistan already has in place one of the world’s most well targeted cash transfer programmes – the Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP). As an immediate top-up to the existing five million families under BISP, the government has enhanced their monthly stipend from PKR 2000 ($13) to PKR 3000 ($20). More recently the government has announced a basic income scheme to provide an emergency cash transfer of Rs 12,000 (compared to a minimum legal monthly wage of Rs 17,500) using data analytics to decide who is eligible to receive cash transfers. It is further expanding the inclusion criteria to provide relief to those on the margins of hunger such as daily wage workers, street vendors, rickshaw drivers, particularly during the lockdown period.

The provincial governments are also gearing up. The government of Sindh is providing relief in cash and kind through a mechanism of self-targeting where the needy call a designated telephone line. The process to determine eligibility is being refined alongside the rollout.

Protecting businesses

Setting the right foundation to kick-start the economy is imperative for the government. The economic stimulus package contains a whole range of fiscal measures (tax breaks, financial support via utilities, fuel and transport subsidies, concessions and tax refunds) to protect exporters and businesspersons. The government has also announced a separate package worth PKR 100 billion ($600.42 million) just for SMEs, which form close to 90% of all enterprises in Pakistan and generate 40% of non-agriculture employment.

The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) has announced a Temporary Economic Refinance Facility to fuel new investment. This will offer subsidised loans to the manufacturing sector and a Refinance Facility to allow banks to get loans at zero mark-up, which they can offer to hospitals at 3% for five years. The SBP has also reduced the interest rate to 11%, still much higher than other countries that have cut down, but 150 basis points lower than before.

More recently the central bank has introduced a new refinance scheme to avoid layoff of workers in exchange for a loan at very low markup rates (5%).

Concluding remarks: The challenges remain severe

Such pandemics expose the inadequacies of the responses of successive governments to poverty, healthcare, and inclusive social protection and governance.

Some questions and thoughts for policy practitioners and researchers to ponder over. How can experts build a trajectory of how the disease is progressing in Pakistan, based on scientific and robust models using contextualised data? How can existing health management structures be leveraged across all levels of governance to enhance the overall national capacity to respond to the crisis? What policies can be adopted to protect the especially vulnerable segment of the population engaged as informal workers and not being targeted by existing social protection/relief strategies? Lastly, how can the plethora of information and data coming in, be used strategically to help the government plan and formulate strategies?

While one cannot predict what will spur the next major epidemic and when, early action can help prepare governments to handle it better. However, any strategy that counters such a pandemic must address underlying vulnerabilities. The challenges facing Pakistan in the current crisis are stark, and it remains to be seen whether the huge interventions that the government has undertaken will be enough to mitigate the loss of life and economic hardship.

Hina Shaikh is a Country Economist at the International Growth Centre (IGC).

This is an updated version of the article which first appeared on the International Growth Centre’s website here.