Context

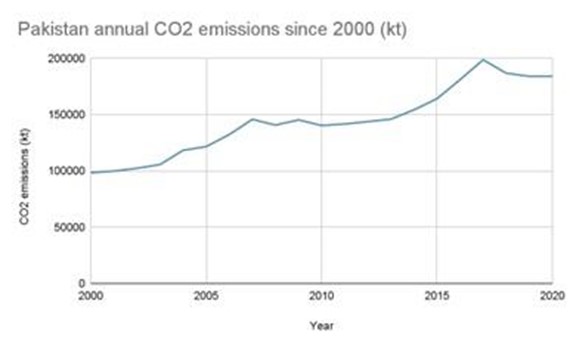

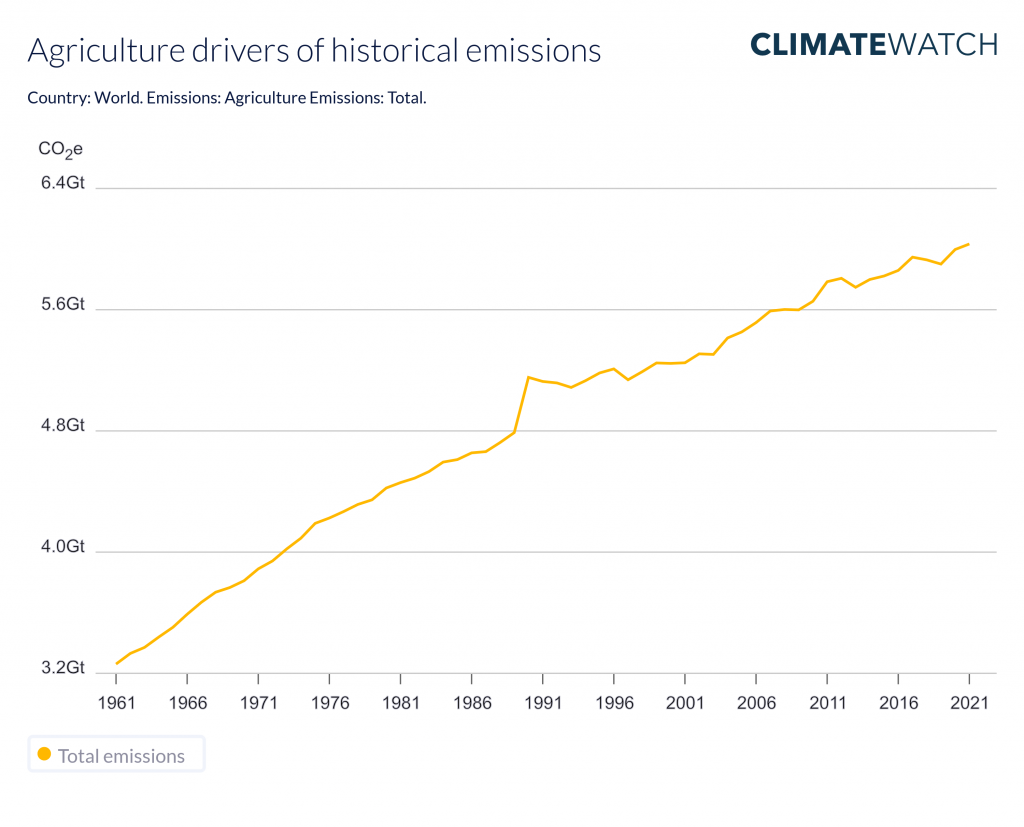

Green technologies are transforming agriculture, by enhancing the efficiency of farming practices and making it more environmentally friendly, and resilient to climate change. They provide sustainable solutions for environmental challenges and facilitate a green economy. With global agricultural emissions reaching 5.86 gigaton of CO₂e in 2021—representing 12.16% of total global emissions—the urgency for sustainable solutions is growing greater. Countries across the world have been adopting green technologies to transition towards a more sustainable and circular economy.

https://www.climatewatchdata.org/sectors/agriculture

This blog explores global best practices in sustainable agriculture and how Pakistan can leverage similar solutions to mitigate its air quality crisis, which is exacerbated by the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from its agricultural sector.

Green Technology – Pakistan vs the World

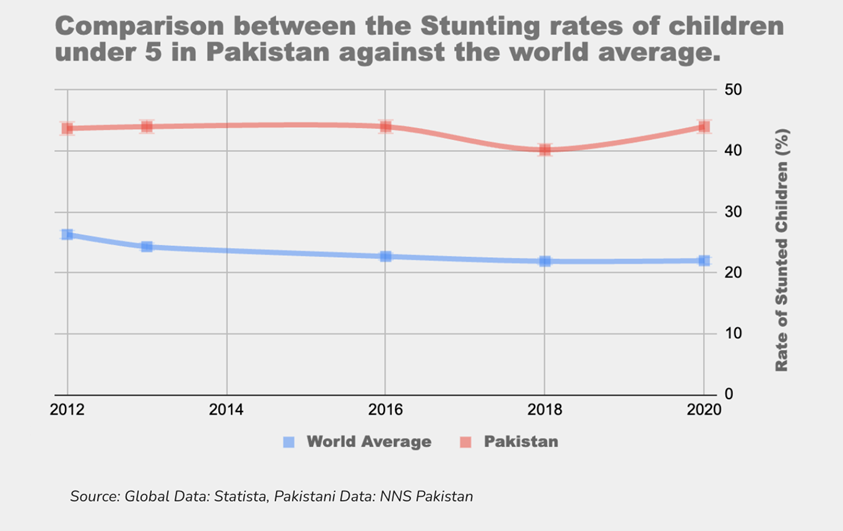

Pakistan faces a unique set of challenges. Urban air pollution results in an economic loss of Rs. 65 billion per year, resulting in a deterioration of the socioeconomic progress of the country. The country’s air pollution is largely attributed to vehicular fumes, industry emissions, agriculture and brick kilns, with agricultural emissions contributing to 20% of the province’s overall air pollution. While rice stubble burning after harvest is a cost-effective practice for farmers, it is also one of the primary sources of agricultural pollution, releasing smoke and pollutants such as PM2.5 in the air, and harming soil quality.

Similar agricultural challenges have been resolved effectively in other countries. For example, China, one of the world’s largest agricultural economies, faced a comparable problem of producing up to 1 billion tonnes of crop residue annually. Until the early 2000s, most of this residue was burned, resulting in 9 million tonnes of GHG emissions each year. In response, the government launched green initiatives to transform its farm waste management, by processing millions of tonnes of crop residue into clean energy via biogas plants. This not only reduced China’s GHG emissions but also supported the country’s transition towards green energy.

Pakistan also has the potential to transition towards a greener economy, as the country could generate approximately 28 million m3 of biogas on a daily basis, meeting over 50% of its power needs. In 2009, the Pakistan Domestic Biogas Programme aimed to install 300,000 biogas units across the country was initiated, but it only installed 5,360 units by 2014 (there is no available data on whether these plants are still functional today or how many more have been installed under this programme). Thus, much of Pakistan’s abundant supply of biomass still remains untapped, and has yet to be sustainably integrated into its energy mix. In order to mitigate its agricultural emissions crisis, the country needs to upscale biogas plant installations and integrate this green fuel into its energy mix.

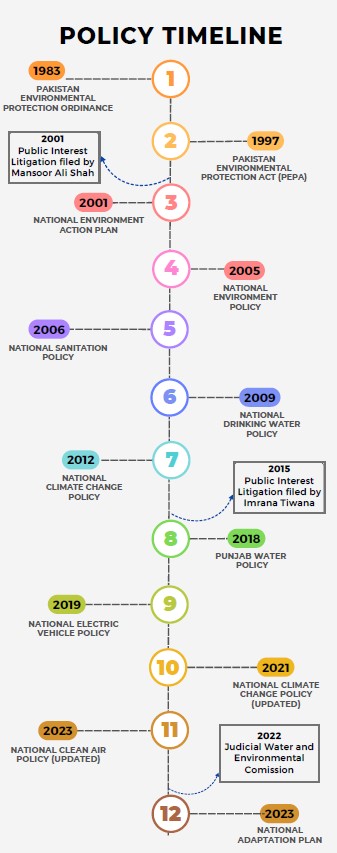

Another relevant global best practice example is that of Denmark, which also struggled with high GHG emissions from its livestock and farming sector. Its government launched a “Green Growth” Initiative, driven by Denmark’s Climate Act – a legally binding framework with year-wise targets for sector-specific measures for a green transition. The country pushed both its public and private sector towards achieving strict environmental goals. As a result, Denmark met its 2020 emissions target ahead of time, and has legally bound itself to achieve climate neutrality by 2050.

In contrast, Pakistan’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) have set a “cumulative conditional target” to reduce 50% of its projected emissions, by 2030. However, the country aims to achieve only 15% of this emissions target via its own capital, and 35% is contingent on international finance. Additionally, the country lacks sector-specific targets, as well as a legally-binding framework for meeting its emissions goal. This results in policy inaction and weak policy implementation. Therefore, in order to ensure progress is made towards achieving its NDCs, the government must enact stringent climate laws and regulations that are aligned towards its long-term policy goals for each sector. It should also conduct robust monitoring and evaluation of its climate action initiatives, and promote public and private sector partnerships for climate finance and investment.

Brazil provides another example of successfully tackling GHG emissions in its agricultural sector. Between 2010 and 2015, Brazil reduced 80% of its permitted land for pre-harvest burning, resulting in a significant decrease in health illnesses such as hospitalizations and respiratory diseases. It offered farmers credit for investments into sustainable agricultural technologies, such as the adoption of mechanised harvesting equipment and promoting the sustainable use of sugarcane residue for bioenergy production.

Pakistan still has a long way to go when it comes to integrating green technology into its farming practices. To combat air pollution, the government introduced the Happy Seeder – a device that allows farmers to mechanically remove rice stubble after its harvest, which incentivizes them against stubble burning. In order to reduce pollutant emissions, the government has supported the transition from conventional brick kilns to eco-friendly zig-zag kilns across Punjab.

As per an ongoing IGC study on “Can subsidising green agricultural technology reduce smog?”, Rice Straw Shredders and Happy Seeders (RSS-HS) machines have the capacity to reduce GHG emissions, improve soil productivity and fertility. However, some barriers that prevent the adoption of green technology in Pakistan include high initial costs of equipment, limited awareness on how to utilise the technology, and lack of long-term policy frameworks for green initiatives. Literature suggests that subsidies for green technology have a positive impact on the use of that technology, as farmers are unlikely to adopt it without financial support. Pakistan can facilitate farmers by subsidizing green technology to reduce crop residue burning and GHG emissions. Increasing financial subsidies for farmers to adopt green technology and simultaneously increasing training programs for giving farmers the awareness and training for its proper utilisation, can have a positive impact on efforts to decrease crop burning.