This blog is authored by LGSi student, Rayaan Ali Rana, as part of CDPR’s Mentorship Programme, in July 2024, and is based on the research study he will conduct on “A Comparative Analysis of the Sustainability of Neighbourhood Structures in Lahore”.

Urban green spaces are vital for residents’ well-being, providing recreation, reducing heat islands, and improving air quality. According to WHO, access to green spaces can reduce health inequalities, improve mental health, and increase life expectancy (Bonn, 2016). Moreover, as per the UN, cities occupy only 3% of the Earth’s land but account for 75% of carbon emissions. Lush, vast greenery in a city indicates natural conservation, providing ideal living spaces with low environmental impacts. However, the sustainability of green spaces remains a contentious issue, as they require significant maintenance resources like water and fertilizers, potentially impacting the ecological footprint of a neighborhood. These green areas might not be as eco-friendly and ideal as we have been made to think.

Exploring the benefits and drawbacks of neighborhood green spaces on sustainability is not only relevant for environmentalists and urban planners but also for citizens who are becoming more conscious of their ecological footprint and want to live in more sustainable communities. This blog aims to provide insights into urban green space management and planning, enabling better decision-making for sustainable communities.

Various studies illustrate the relationship between sustainability and the ecological footprints of different areas. Liaquat et al. (2017) examined Lahore’s urban compactness, highlighting the importance of density, transportation, and land use for sustainability. Similarly, Rashid et al. (2018) analyzed Rawalpindi’s ecological footprint, accentuating excessive resource use and unsustainable lifestyles. Rapid growth and insufficient public transport contribute to greenhouse gas emissions, emphasizing the need for regulations and sustainable transportation systems. The research on Delhi’s urbanization conducted by Rajput & Arora (2017) emphasizes the importance of green spaces and public transport for sustainability. Holden (2004) used his research to suggest that high-density urban areas with short service distances support sustainable development, while unplanned urban expansion and ineffective public services increase ecological footprints. These studies highlight the impact of energy usage, transportation, and urban planning, on ecological footprints.

Studies also show that green spaces offer numerous benefits to urban communities, including relaxation, stress reduction, mood improvement, sleep quality, cognitive function enhancement, and immunity boost. Nature reduces stress hormones, and improves mood, preventing anger, anxiety, and depression (DESI, 2023). Additionally, plants release anti-fungal and antibacterial bodies, aiding in fighting illnesses and fostering a healthy, productive environment.

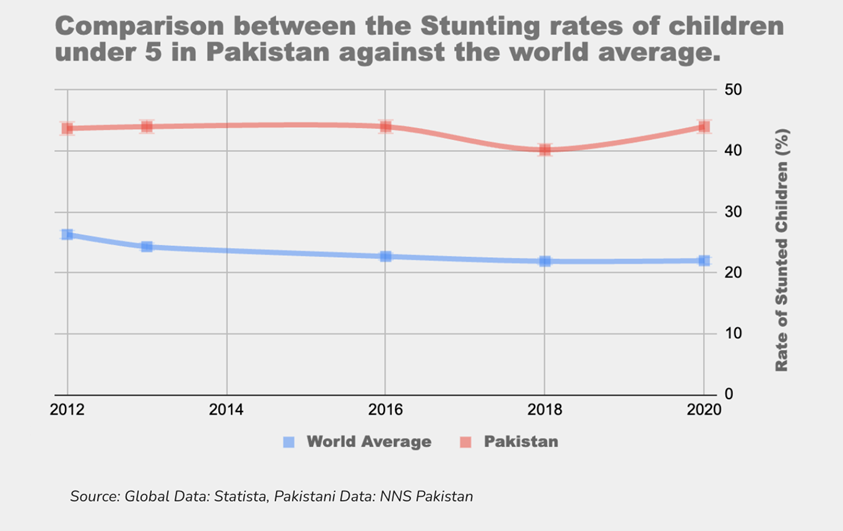

Fig. 1 – Source: World Bank Development Indicators (WDI)

Moreover, they benefit not only people but also the environment. Plants and trees act as effective natural filters by absorbing carbon dioxide (CO2) and replacing it with oxygen (O2). Fig. 1 shows how CO2 emissions in Pakistan have increased by around 86,000 kt since 2000, emphasizing the need for green spaces in urban areas where emissions are high. Lahore has consistently ranked as one of the most polluted cities in the world regarding air quality (IQAir, 2023). Collectively, these highlight the need for abundant green spaces in urban areas, such as trees and plants, as crucial for controlling air pollution. Trees preserve biodiversity by providing a habitat for various species and mitigate the “urban heat island effect,” which occurs when buildings replace natural land cover, leading to increased air pollution, energy expenses, heat-related diseases, and fatalities. Therefore, green spaces offer cooling benefits (DESI, 2023).

There are various real-world examples of communities integrating green spaces into urban areas. Norway’s Oslo is the world’s greenest city with 47% green cover. It has a temperate climate with ample rainfall, reducing the need for artificial irrigation of green spaces, despite its immense greenery. A total of one million trees grow within its urban zone, with two-thirds of the area located within the city’s boundary, and consisting of forests, parks, and lakes (Modeshift, 2023). The city’s extensive natural reserves are well-integrated into the urban landscape. Its green spaces are less water-intensive than arid regions like Dubai, and they are often natural areas that require less intensive maintenance. Thus, Oslo is a leader in urban sustainability, focusing on efficient public transport, green infrastructure, biodiversity conservation, and renewable energy use.

However, urban green spaces can also adversely impact the environment, if the resource consumption and management during its maintenance processes like pruning, weeding, and fertilization, is unsustainable and resource-intensive. For instance, Pakistan’s annual freshwater withdrawals have increased by over 17 billion cubic meters since 2000 (WDI), with 70% used for irrigation (Khokhar, 2017). Although this primarily concerns agricultural irrigation, every extra cubic meter of water used to maintain green spaces places extra stress on the water table, given its finite nature and scarcity within Pakistan, raising sustainability and wastage concerns.

Another example is Dubai, which is one of the least green cities in the world and faces significant challenges in irrigating the limited greenery it has, due to its desert climate. The city’s ambitious greening projects rely heavily on desalinated water, which is an energy-intensive process itself. Thus, Dubai has one of the highest per capita ecological footprints globally, and experts estimate that approximately 42% of the UAE’s municipal water supply comes from desalination, 49% from groundwater, and 9% from treated wastewater reuse (Herber, 2024). To reduce its ecological footprint, the city is implementing sustainability initiatives like smart irrigation systems, sustainable landscaping, and increasing renewable energy in its energy mix. While Dubai uses technology to optimize resource use, Oslo focuses on efficient use of natural resources.

With air pollution increasing temperatures, and urban sprawl becoming a major problem in places like Lahore, Karachi, and Islamabad, green areas hold enormous potential for Pakistan. Pakistan can significantly reduce the urban heat island effect, enhance air quality, and provide people with much-needed recreational space by including well-maintained green areas. In highly crowded places, these spaces may be extremely important for bolstering communal bonding, alleviating stress, and boosting mental well-being.

The tricky part, however, is keeping these green areas sustainable. Pakistan and Dubai similarly face water shortages, with agriculture using the majority of freshwater available. To reduce the environmental impact of green spaces, the nation needs to use innovative irrigation practices, such as the use of treated wastewater and drought-resistant plants. By choosing low-maintenance, native plant species, Pakistan can lower its reliance on external resources like fertilizers and excessive water. Furthermore, the incorporation of green areas needs to go hand in hand with sustainable urban development. Key lessons could easily be taken from Oslo’s example of prioritizing renewable energy consumption, green infrastructure, and public transportation. Alongside effective, environmentally friendly transport systems, Pakistan’s cities—which suffer from inadequate public transit and increased pollution—should concentrate on developing green belts. This would improve the quality of the urban environment in addition to lowering greenhouse gas emissions.

Ultimately, green spaces have the potential to become a vital component of Pakistan’s sustainable urban growth, improving public health, conserving the environment, and raising everyone’s standard of living.

Works Cited

Bonn. “Urban Green Space and Health: Intervention Impacts and Effectiveness.” World Health Organization, 2016, https://www.who.int/andorra/publications/m/item/urban-green-space-and-health–intervention-impacts-and-effectiveness.

AMartinMartin, MartinRuna. “Cities – United Nations Sustainable Development Action 2015.” United Nations Sustainable Development, 7 Jan. 2015, https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/cities/. Accessed 6 Aug. 2024.

Holden, Erling. “Ecological Footprints and Sustainable Urban Form.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, vol. 19, no. 1, 2004, pp. 91–109, https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOHO.0000017708.98013.cb.

Liaqat, Hussain, et al. “Measuring Urban Sustainability through Compact City Approach: A Case Study of Lahore.” Journal of Sustainable Development Studies, vol. 10, no. 2, Oct. 2017.

Rajput, Swati, and Kavita Arora. “Analytical Study of Green Spaces and Carbon Footprints.” Springer International Publishing, 1 Jan. 2017, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-47145-7_23.

Rashid, Aadul. “Ecological Footprint of Rawalpindi; Pakistan’s First Footprint Analysis from Urbanization Perspective.” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 170, Jan. 2018, pp. 362–68, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.186.

Khan, and Siddiqui. “Estimation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Household Energy Consumption: A Case Study of Lahore, Pakistan .” Pakistan Journal of Meteorology, vol. 14, no. 27, July 2017.

“Why Are Green Spaces Good for Us?” Department of Environment, Science and Innovation (DESI), Queensland, 23 Oct. 2023, https://www.desi.qld.gov.au/our-department/news-media/down-to-earth/why-are-green-spaces-good-for-us. Accessed 31 July 2024.

FRDA, Karen Cerquera /. Translated by: “Steps to Keep in Mind for the Maintenance of Green Areas.” NW Group, 30 Mar. 2022, https://www.reddearboles.org/en/news/nwarticle/506/2/steps-to-keep-in-mind-for-the-maintenance-of-green-areas. Accessed 31 July 2024.

Herber, Gunnar. “Exploring the Top Desalination Plants in UAE: How They Are Meeting the Country’s Water Demands and Contributing to Sustainability.” Medium, 23 May 2024, https://medium.com/@desalter/what-are-the-top-desalination-plants-in-uae-and-how-do-they-contribute-to-the-countrys-water-755989bd6c91. Accessed 31 July 2024.

“Home.” Emirates Green Building Council, https://emiratesgbc.org/uae-sustainability-initiatives/. Accessed 31 July 2024.

Modeshift. “Article Headline.” Modeshift, 21 Feb. 2023, https://www.modeshift.com/oslo-is-ranked-one-of-the-most-sustainable-cities-in-the-world-heres-why/.Accessed 31 July 2024.

“World’s Most Polluted Cities in 2023 – PM2.5 Ranking.” IQAir, https://www.iqair.com/world-most-polluted-cities.

“World Development Indicators.” DataBank, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators. Accessed 5 Aug. 2024.

Khokhar, Tariq. “Chart: Globally, 70% of Freshwater Is Used for Agriculture.” World Bank Blogs, 22 Mar. 2017, https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/chart-globally-70-freshwater-used-agriculture.

Ansari, Ahmad Ahsan. The Disappearance of Green Spaces Has Become Synonymous with ‘Development.’ How Is Lahore, Pakistan Dealing with It? 17 Sept. 2020, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/disappearance-green-spaces-has-become-synonymous-how-lahore-ahmad.