By Shehryar Nabi

Pakistan’s expanding, largely urban middle class shows a country far different from its traditional poles of poor and elite.

How should we understand Pakistan’s middle class – a phenomenon inseparable from its economic and political future?

On October 31st, the Lahore-based Consortium for Development Policy Research co-organized an event with the Urban Institute in Washington D.C. to assess this question. The event featured a panel of researchers studying middle class trends both globally and in Pakistan.

Here are key takeaways from the conversation:

We know the middle class is growing, but it remains ill-defined

There is plenty of anecdotal evidence of the middle class in Pakistan. Go to any major city, and you will see consumerist lifestyles that, as described by World Bank Economist Ghazala Mansuri at the event, are free from the depravations of poverty but still depend on public services that the rich opt-out of.

But how big is the middle class in numbers?

There are two government sources used to size up Pakistan’s middle class: National income accounts and household consumption surveys. Combining these measures, and using the global middle class definition of $11 to $110 in daily income[1], Brookings Institution Senior Fellow Homi Kharas found that about 50 million Pakistanis are middle class, comprising 27 percent of the population. By 2030, that number is forecast to reach 160 million people, 66 percent of its population. That would make it the 13th largest middle class in the world.[2]

Mansuri commented that economic definitions of the middle class can vary wildly, making these figures imprecise. But existing measures at least confirm that Pakistan’s transition to a middle class society is in full swing.

How the middle class changes society

The rise of Pakistan’s middle class has broad implications for society, detailed at the event by Homi Kharas.

Firstly, the rise of the middle class has a varied effect on climate change. On the one hand, a growing middle class exacerbates climate change by increasing overall consumption, and thus carbon emissions. On the other hand, the middle class tends to be educated and live in smaller households, both of which are associated with lower carbon footprints.

The middle class also has an important effect on population growth. Pakistan’s fertility rate has been declining since the 1980s, and a growing middle class is likely to slow down population growth even more. If this is indeed the case, then the projection of the middle class described above would be too high because it does not account for a lower fertility rate.

Demand for education, the surest pathway for moving up the socioeconomic ladder, is driven up by the middle class.

Will the middle class strengthen democratic institutions? Kharas remarked that global experience suggests that rising prosperity and authoritarian government are by no means mutually exclusive. Nor are existing democratic institutions necessarily safeguarded by the middle class.

Kharas observed that because the middle class tends to demand public services, political tensions can stem from service delivery failures that spark distrust in the government. The evidence on this is in Pakistan mixed. A recent survey in Lahore shows that public service delivery is high on the minds of voters. Yet despite public service delivery failures – which Ghazala Mansuri pointed out have remained especially dire in Karachi despite a growing middle class – the expected political reaction has not been pronounced. This suggests that the middle class is not mobilized to demand accountability for service delivery through the political system.

The rise of the middle class does not guarantee gender equality

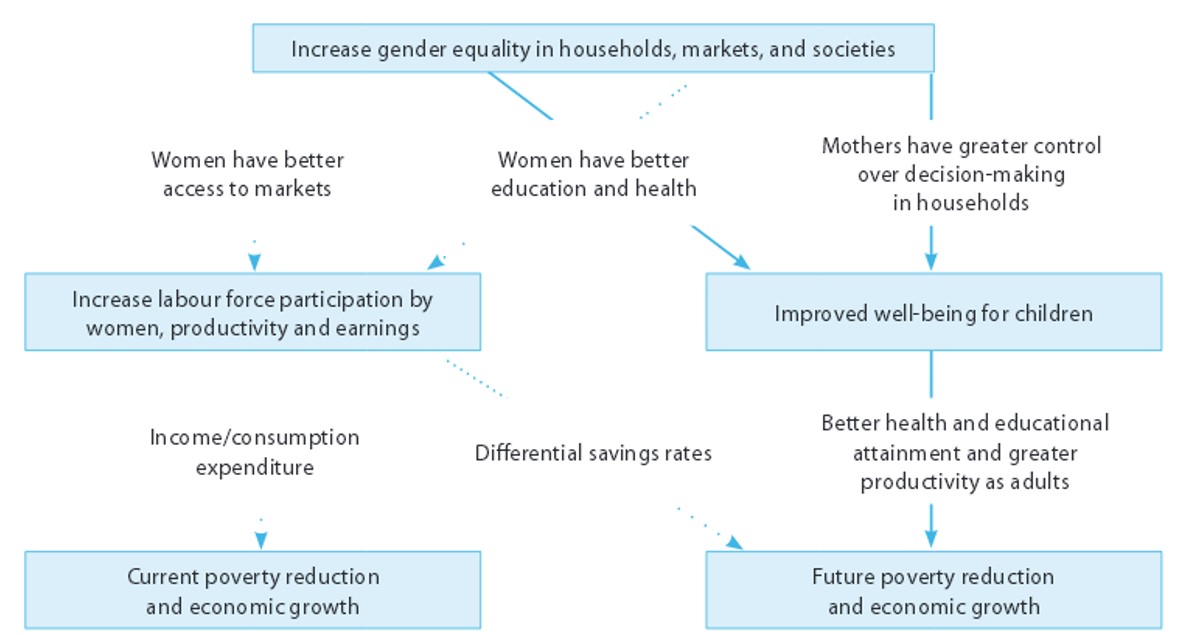

There are intuitive reasons why a rising middle class anticipates better outcomes for women. Middle class incomes may be driven by women earners in the family, increasing demand for their education, and in effect empowering them to make choices beyond the constraints of patriarchal norms.

But the evidence from Pakistan shows the path to empowerment is not so straightforward.

Drawing on data from 2005 to 2015, Urban Institute Research Associate Reehana Raza first pointed to trends that suggest a positive impact of middle class growth on women’s empowerment. In urban areas, which are strongly associated with the middle class, women’s enrollment in secondary education increased by 10 percent. Women’s enrollment in tertiary education grew from 200,000 to 600,000. Raza also found that income returns for each additional year of schooling are higher for women than for men.

However, this isn’t translating into substantial gains in employment. Although women’s employment is on an upward trend, only 25 percent participate in the labor market. Just 20 percent of women with a bachelor’s degree enter the labor market. Women who seek employment tend to do so after receiving at least ten years of schooling, whereas men can find work at any level of education. Raza concluded that while high income returns demonstrate an opportunity for women to benefit from education, it isn’t being reflected in Pakistan’s workforce.

Does the middle class increase women’s political representation? According to ongoing research in Lahore led by Ali Cheema, Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives, the gender gap between men and women’s votes remains high in urban areas where the middle class has grown. Ali Cheema discussed what his research shows about the gender gap at the event.

One theory is that patriarchal norms at the household deny women their right to vote, or their votes are decided for them. But Cheema’s team found a different story. Women are in fact not prohibited from voting, and voting decisions are largely their own. They also found that divergences in women and men’s votes can have important consequences for electoral outcomes.

A different explanation offered by Cheema is the persistence of patriarchal norms at the party level. Cheema’s team found that party organizers and the movements they build are overwhelmingly male. This suggests they are unengaged with potential women voters.

Surveys conducted earlier this year by Cheema’s team show that women feel invisible to political parties, leaving them unenthusiastic about elections. Women are 21 percent more likely than their male counterparts to strongly agree that political parties are only interested in men’s votes.

Cheema argued that to reduce the gender gap in voter turnout, there needs to be a greater focus on the exclusionary tendencies of existing political structures even where the middle class is growing.

What we need to sustain middle class growth

Pakistan’s middle class surge is not inevitable if economic, social, and political structures remain as they are. At the event, ways to ensure the middle class’s continued expansion were floated with the audience for discussion.

Homi Kharas argued that the future of middle class jobs will not be in the manufacturing sector, the conventional pathway from lower to middle-income country status. Rather it will be in services – education, health, banking, telecommunications, etc. Kharas highlighted that the dynamism of the services sector creates wide opportunities in the job market. However, services will have to be tradable to drive middle class growth. Right now, however, Pakistan does not have internationally competitive services other than migrant labor.

A neglected avenue of middle class growth, Ghazala Mansuri argued, is agriculture. Mansuri stressed that the largely urban phenomenon of the middle class should not lead to the neglect of rural areas, which currently suffer from low productivity and poor service delivery.

The final, but highly important priority emphasized by Kharas is increasing women’s employment. Pakistan’s middle class is exceptional in how few women enter the labor market. For other middle-income countries, like China and Malaysia, incorporating women into the workforce was pivotal for overcoming widespread poverty and raising living standards. Unless social and structural barriers that prevent women’s labor force participation are removed, sustaining Pakistan’s middle class will be a challenge.

Shehryar Nabi is a communications associate at the Consortium for Development Policy Research.

[1] However, middle class trends have been observed among Pakistanis earning $5 to $10 per day.

[2] Kharas added a big caveat to his methodology. If you judged Pakistan’s by its national income accounts, it would be slightly richer than Bangladesh. But if you just looked at household consumption surveys, which do not account for 60 percent of national income, Pakistan would be poorer than Kenya or Cameroon. Household surveys fall short because questionnaires miss several modes of consumption, omit the informal sector, and are often unanswered by the top 10 percent.