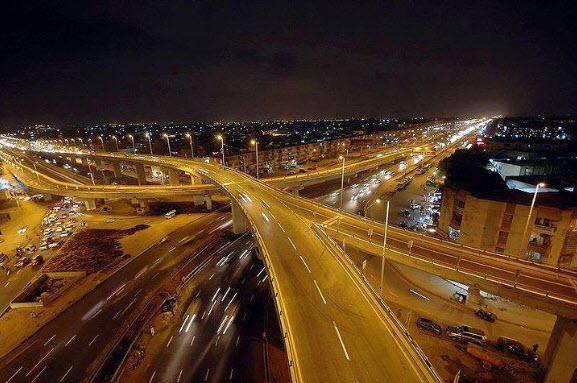

(Image: Flickr user junaidrao, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Shehryar Nabi

Whether you are a pessimist or an optimist about the future, 2016 was indisputably a pivotal year for the world. Here’s a recap of the changes both in and out of Pakistan in 2016 that will affect its development path:

1. Poverty was re-defined

The poverty rate increased significantly this year after the government updated its own methodology for determining poverty, and found that 30 percent of Pakistanis are poor.

The United Nations Development Programme also released Pakistan’s first-ever multidimensional poverty index, which uses non-wealth indicators such as education and health to measure poverty. Using this method, Pakistan’s poverty rate comes to 39 percent.

The good news is that no matter the measure, the poverty rate has been declining overtime, albeit unevenly across different regions.

As argued here, efforts to re-define poverty indicate a willingness to adapt the measure for better anti-poverty interventions. This means that more poor people living above the official poverty line can be targeted by poverty reduction efforts.

2. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor became functional

The first Chinese ship docked at Gwadar port to receive goods transported along the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) for sale in global markets, opening CPEC to international trade. The government estimates that the $54 billion Chinese investment in infrastructure and energy will create 800,000 jobs and boost Pakistan’s GDP growth rate from its current 4.7 percent to 7 percent in 2018.

But CPEC enthusiasts shouldn’t express their jubilation at the initial investment alone. The transformative effects of CPEC will only be felt if regions adopt policies to accommodate it, and local entrepreneurs seize the opportunity.

CPEC is also tightening Pakistan and China’s military relationship, raising eyebrows in India.

3. More protections for women were legislated

Two bills giving women greater legal protection from physical and sexual violence were passed in 2016.

In February, the Punjab assembly passed the Protection of Women Against Violence Act, which expands the kinds of actions women can report as violence and establishes a process for reporting abuse, protecting victims and bringing cases to court.

In October, parliament passed anti-honor killing and anti-rape bills. The new laws prevent the victim’s family from forgiving the perpetrator of an “honor killing” (unless the perpetrator is sentenced to a capital punishment) and, for rape cases, set a three-month time limit for determining verdicts, require DNA testing as evidence and impose a minimum prison sentence of 25 years for the offender.

The Protection of Women Against Violence Act was criticized by the Council of Islamic Ideology as being un-Islamic and unconstitutional.

Activists praised the bills as a step in the right direction, but there is concern that the laws do not go far enough and lack proper implementation.

4. The International Monetary Fund ended its stabilization program

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) ended its US $6.7 billion, three year stabilization program that increased Pakistan’s foreign reserves enough for four months of imports, reduced its deficit from 8 to 4.3 percent and maintained a steady outlook for economic growth.

While Pakistan is safe from an external shock to its economy for now, the IMF may come back if necessary reforms to make Pakistan resilient to global economic shifts are delayed for too long.

5. Relations soured with Afghanistan . . .

Continued criticism from Afghan President Ashraf Ghani that Pakistan has not done enough to prevent cross-border terrorism, skirmishes at the Khyber Pass and plans to deport 3 million Afghan refugees could further slowdown Pakistan and Afghanistan’s trade relationship and hurt regional cooperation.

6. . . . and India

The glimmer of hope for India-Pakistan relations established after Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s surprise visit to Lahore quickly faded when terrorists allegedly based in and supported by Pakistan killed seven Indian soldiers and one civilian at Pathankot air force base, 19 soldiers at Uri and seven soldiers at Nagrota in India-administered Kashmir.

Anti-India sentiment was also inflamed in Pakistan after the Indian army cracked down on Kashmiri protesters, killing 89 and causing eye damage to thousands, many of whom became permanently blind.

Bollywood banned Pakistani actors, and Pakistan banned Bollywood films (until recently). India carried out “surgical strikes” against terrorists in Pakistan – although official and civilian narratives of the strikes differ. There were more cross-border firings between Pakistani and Indian soldiers. The Indus Waters Treaty came under threat.

While improved India-Pakistan relations are desirable for expanding trade, cultural exchanges and preventing war, the events of 2016 do not bode well.

7. Pakistan became Asia’s best-performing stock market

The Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad stock exchanges merged into the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX), which became Asia’s best-performing stock market with an increased value of 27 percent.

Recently, a Chinese-led consortium acquired a 40 percent stake in the PSX, with the hopes of drawing more Chinese investment into Pakistan’s economy.

8. The Panama Papers changed politics

The anti-corruption agenda spearheaded by the leading opposition party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), was bolstered by the Panama Papers investigation that revealed Nawaz Sharif’s children as among the global rich and powerful who hold large offshore accounts.

While there is currently no evidence that the money was extracted through corrupt means, the issue has become a thorn in the side of the ruling Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN) for the 2018 election. With a PMLN victory, voters can expect a continuation of the energy-expanding, infrastructure-building focus of development policy. But if the Panama issue remains potent, securing a PTI win, Pakistan may change course.

9. Pakistan became committed to global CO2 reduction targets

In November, Pakistan ratified the Paris Agreement, which commits countries to reduced CO2 emissions targets. Pakistan also passed the Climate Change Bill 2016, which proposes measures for mitigating the effects of climate change. However, having different ministries implement the measures will be a separate, though important challenge given the threats climate change poses to flood risk, food security and the overall economy.

10. Power generation costs continued to fall

Lower global oil prices and the expansion of wind, hydel, coal, solar and nuclear power projects have made power generation much cheaper, as seen by a recent 50 percent cost reduction in November. Energy costs will likely fall even further if more power companies are privatized, and CPEC energy investments are made next year. The government is hoping that by the 2018 election, regular blackouts will end. However, if power losses from transmission and distribution and inefficient energy usage are not addressed, blackouts will likely return.

11. Infrastructure, infrastructure, infrastructure

New highways. Upgraded railroads. Metro lines. Pakistan’s push for modern infrastructure intensified in 2016.

There is a view that the government is giving infrastructure too much focus and, as a consequence, neglecting the education and health sectors. Others argue that better infrastructure is a form of economic justice.

12. Polio moved closer to eradication

In 2014, there were 306 new cases of polio in Pakistan, a significant increase from preceding years. In response, the government began carrying out regular vaccination drives. This year, only 22 new cases of polio were reported.

The final push to complete eradication still poses challenges, as health workers administering vaccines are threatened by attacks and outdated systems for managing anti-polio drives could leave some children unvaccinated.

13. A cure for Hepatitis C became more affordable

According to Pakistan’s health ministry, about 8 million Pakistanis have Hepatitis C, and 80,000 die from the disease every year. The most effective treatment for the disease is the drug sofosbuvir, but unless a local pharmaceutical company has the rights to produce a generic version, it costs US $1,000 per pill.

This year, the Pakistani pharmaceutical Ferozsons acquired those rights and began manufacturing the drug to be sold at a slashed price of $56 for 28 doses. While poor sanitation and dirty needle use will likely keep Hepatitis C prevalence high, the availability of a low-cost treatment will undoubtedly save lives.

14. A program to reduce malnourishment began

With the support of the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development, Pakistan launched a food fortification program to fight malnourishment. 44 percent of Pakistani children under five have stunted growth from malnutrition, slowing their cognitive ability and increasing their susceptibility to disease. The program will add micronutrients to flour and edible oils with the hopes that in five years, they will be consumed by over half of the population.

15. The West saw a historic political shift

Pakistan will likely feel the effects of the major political and economic changes in the West: the election of Donald Trump to the United States presidency, Britain’s exit from the European Union and the rise of political parties that favor less trade, less foreign aid and less immigration.

Pakistan may be caught in an awkward position vis-à-vis relations with China and the US if they engage in a trade war, foreign aid could decline and discouraged Pakistani migrants in the West might cause a drop in remittances.

These possibilities and more will be examined in greater detail for a future post.

Shehryar Nabi works in communications for the Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR) and the Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives (IDEAS)