By Hina Shaikh and Ijaz Nabi

Safe drinking water is a central plank of a country’s health strategy as it affects nutrition intake and therefore infant mortality, child growth, and the ability of adults to be productive. Exposure to unsafe water also leads to skin-related disease. For these reasons, access to safe drinking water is a right enshrined in the constitution and is a critical Sustainable Development Goal.

The Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR) recently brought together a panel of experts to discuss the current status of drinking water in Pakistan and what is being done to ensure that citizens enjoy this constitutional right.

Pakistan’s “water stress”

The panel distinguished between “water scarcity” and “water stress”. With the world’s fourth highest rate of water use, Pakistan’s economy is one of the most water-intensive in terms of cubic meters consumed per unit of GDP. Subsequently, water availability per capita has shrunk to under one thousand cubic meters by 2017 from over five thousand in 1951. Pakistan crossed the “water scarcity line’” in 2005, indicating a shortage of overall supply. With higher than expected population growth, this is likely to get worse.

The focus of the discussion was primarily on “water stress”, or the prevalence of polluted water that is unsafe to drink. Panelist Syed Hasan, Assistant Professor of Economics at the Lahore University of Management Sciences, noted that Pakistan became a water-stressed country in 1990 and is expected to be among the most water-stressed countries in the world by 2040.

Panelist Hammad Khan, Director General of World Wild Fund for Nature (WWF) Pakistan, pointed out that the level of arsenic in the water supply far exceeds the government’s own thresholds for contamination, which are in fact less conservative the World Health Organization’s (WHO) standards. A 2015-16 nation-wide survey by the Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR) found that only a third of the 369 samples tested for water quality were safe for consumption. A separate PCRWR study conducted in 2011 found 100 percent of water samples in Lahore were polluted with arsenic. A study led by Joel Podgorski, a scientist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, found that water in two-thirds of the 1200 wells sampled across Pakistan exceeded the WHO-recommended threshold of arsenic. Based on this data, nearly 60 million citizens are estimated to be consuming toxic ground water.

Microbial pollution is also common. In cities, water becomes contaminated due to improper disposal of solid waste and continued usage of outdated water and sewage networks. Chemical pollutants from industrial waste also infect water. In rural areas, open defecation and animal waste are the leading sources of contamination.

Poor quality of water burdens the health sector, increases missed days of work, and reduces labor productivity. High levels of arsenic in water contributes to underweight birth, skin defects and miscarriages. Syed Hasan mentioned the burden of poor health outcomes in the form of waterborne diseases costs Pakistan 1.6 million disability-adjusted life years – and almost four percent of GDP.

Poor governance

Pakistan has been unable to incentivize conservation and efficient usage of water. Syed Hasan commented on the pricing mechanism and its failure to reflect the true market value of this critical resource. The tariff for water used for household consumption in urban Pakistan was last revised in 2004. Operation and maintenance costs incurred by water authorities continue to exceed the revenue they collect, while water metering covers only eight percent of the households.

Hammad Khan explained that if sources of water remain unprotected, the availability of drinking water will keep dwindling. Ground water once contaminated cannot be treated. The installation of filtration plants by Punjab’s Saaf Pani Company (see below), meant to cover all union councils in Punjab, are remedial measures – not sustainable solutions. The unrelenting adulteration of water sources despite decades of several dedicated water authorities in operation reflects a serious governance failure.

The government response in Punjab

Following devolution, water became a purely provincial subject. Punjab set up the Saaf Pani Company three years ago to ensure provision of drinking water in rural Punjab. The company’s progress is personally overseen by the chief minister.

Panelist Tahir Majid, Chief Technical Officer, Punjab Saaf Pani Company, agreed that despite being the Punjab government’s flagship initiative and substantial public expenditure, progress has been slow. A third of the water schemes in the province remain non-functional while 79 percent provide water that is unsafe for consumption.

The problem with Saaf Pani Company reflects a deeper problem of governance pervasive across several other sectors. When parallel governance structures are set up in the presence of existing departments, such as the Punjab Health and Engineering Department, inefficiencies slide in. The company saw several quick changes in senior management (some resulting in criminal inquires) and frequent changes in the operational design. This has resulted in delays and has not encouraged strong private sector engagement in the delivery of safe drinking water to the citizens.

After being heavily scrutinized for its performance, the company is now restructuring itself to improve delivery and remains committed to providing clean drinking water to Punjab’s entire unserved population of 60 million by 2025.

What can be done?

It is encouraging that “water-stress” can be overcome. Singapore’s example, cited by Syed Hasan, shows how the risk of extreme water stress can be countered by efficient regulation and management. Inaction, however, may result in a crisis similar to the one in Cape Town, a city that is now on the verge of rationing clean drinking water.

The panel suggested immediate steps Pakistan can take to tackle the water crisis and avoid the Cape Town outcome:

Set the right priorities: An over-arching water policy framework is critical. The National Water Policy, in circulation since 2004, should be updated in light of changes and approved.

Set water classification standards: Every country (including India, Bangladesh, and China) has water classification standards where all the water bodies are categorized according to their usage. This should also be done in Pakistan. WWF has offered to use remote sensing and GIS mapping to help government conduct this exercise. Authorities will then be able to ensure more effectively that water bodies classified for drinking purposes are kept clean and used for that purpose alone. Water classification will also help avoid disputes between different stakeholders (agriculture vs. industrial vs. household consumption).

Let prices work: Even though water is a basic right, it is a limited resource and hence water pricing is important. The fact that people pay for bottled water indicates that there is willingness to pay.

Mobilize community ownership: Community ownership is key to ensuring that water schemes remain functional and well-maintained. The WWF for example signs a legal contract with the community for joint ownership of the filtration plants it has provided.

Hina Shaikh is a Pakistan country economist at the International Growth Centre.

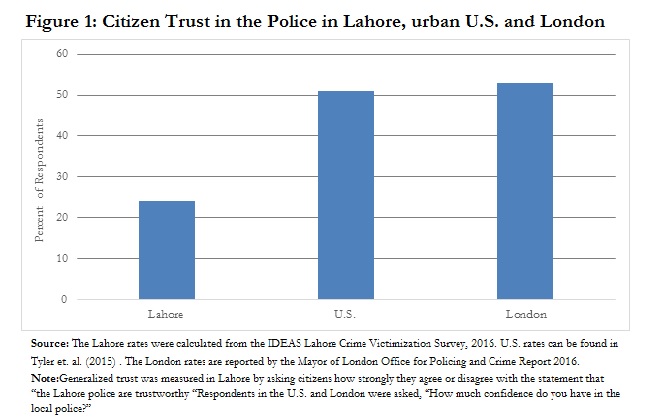

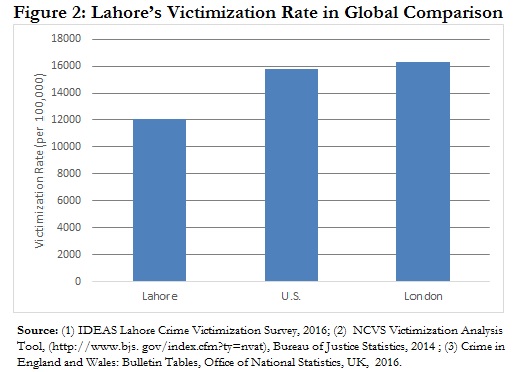

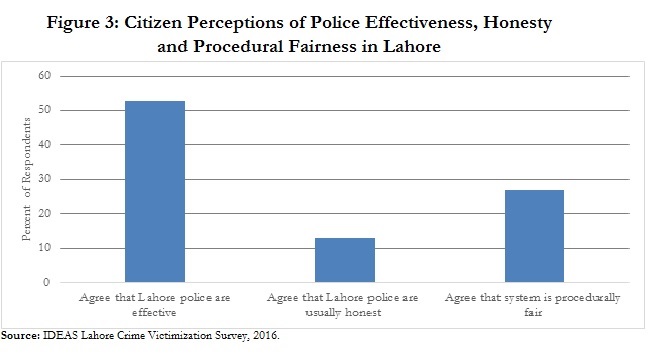

Which parts of the policing process are adversely impacting citizen trust? We find that the First Information Report (FIR) registration system is a particularly pernicious cause of low citizen trust. Our evidence shows that the percentage of victimization incidents (reported in crime surveys) registered as criminal cases (reported in the police’s case registration data) – what we call the registration rate – was far lower in Lahore than in London and the Urban U.S. in 2016.

Which parts of the policing process are adversely impacting citizen trust? We find that the First Information Report (FIR) registration system is a particularly pernicious cause of low citizen trust. Our evidence shows that the percentage of victimization incidents (reported in crime surveys) registered as criminal cases (reported in the police’s case registration data) – what we call the registration rate – was far lower in Lahore than in London and the Urban U.S. in 2016.