By Shehryar Nabi

Regime change never seems to quell the same struggle that has persisted since stories have been told: the struggle between authority and dissent.

This was the sense that Osama Siddique imagined was familiar across epochs in his time-traveling debut novel, Snuffing Out the Moon.

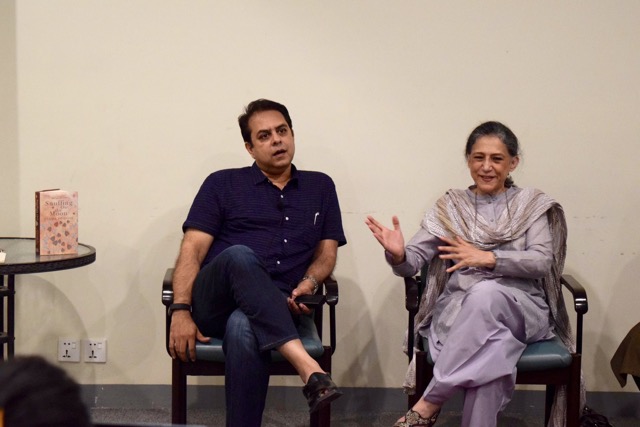

Speaking on August 8th to a live audience with Faisal Bari, Director of the Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives (IDEAS), and Ayesha Jalal, Tufts University Professor and eminent historian of South Asia, Siddique discussed the themes and motivations that shaped his new book. This is Siddique’s first foray into literature – he is otherwise known as a widely-published legal scholar who has held numerous advisory and academic positions with institutions such as the Lahore University of Management Science (LUMS), IDEAS, and Harvard Law School.

Set in what is today Pakistan, Snuffing Out the Moon progresses over six eras: Mohenjo Daro, Taxila, the Moghul Empire under Jahangir, the fall of the Moghul Empire in 1857, Lahore in 2009 during the Lawyers’ Movement, and 2084, a future where South Asia is controlled by water conglomerates. The plot is not contiguous across eras, each of which marks a new story with new characters. This narrative style allowed Siddique to animate the novel with the different sights, sounds, and smells of changing realities. It also afforded him the opportunity to write with a diversity of idioms unique to each era.

But Siddique’s true aim was to convey the recurring nature of oppressive power, the common folk’s struggle to cope with it, and most importantly, the beacon of resistance. Within this paradigm he explored how illusions, omens, loathing, passion, and dissent play out in a way that, as Mark Twain allegedly put it, “rhyme” over history. These themes cohered the disparate stories.

“Can I do something which can actually tell multiple stories which have nothing to do with each other and yet have everything to do with each other?” Siddique said he asked himself this question when considering the novel’s structure.

He also cited Qurratulain Hyder’s Urdu-language novel Aag Ka Darya – which took place across different historical eras – as a key influence on the book.

“That work had a huge impact on me aesthetically, in terms of its imagination, in terms of what it set out to do,” he said.

In Snuffing Out the Moon, the light of human spirit championed in resisters co-exists with the darkness of reality. To dissent is to exile, whether breaking physically from society or mentally from your peers, or both. No resistance is ever the same – a teacher and an armed rebel could both find themselves in the dissenting camp. But regardless of the form it takes, resistance necessitates at least some degree of suffering as the price for espousing norm-breaking ideals.

Using this as the central tension driving the stories of rebel protagonists, Siddique makes them out to be the real idols of history. Greatness is not being a king or general, but an exile surviving on the margins of accepted thought.

“There was a very conscious effort to create heroic figures out of dissenters. I wanted to do my little bit in terms of highlighting the sacrifice, the independence of mind, the self-abnegation that goes into being a dissenter,” Siddique said.

Ayesha Jalal asked Siddique about how his background in law informed the book. Siddique first made clear what kind of legal scholar he is. He takes less interest in high profile cases such as the Panama leaks, and rather focuses his research on law as a sociological phenomenon: how law creates hegemony, how it is used to coerce, and how it provides unequal benefits depending on class, gender, and other categories.

This understanding of legal regimes and power – which he has spent a career explaining in books and papers – is re-imagined in the book through the perspectives of people who have to endure them.

“What I’ve tried to do is take everyday characters and show how they interplay with the formal legal system . . . it has a presence and a reputation which is looked upon as something which is sacred – you can’t question it,” Siddique said.

Following this discussion of the sociological dimension of law, Siddique promised that the book would explore these ideas without sounding academic.

“It’s a bit more interesting in the book, I assure you,” he said.

Why should we care about dissent today? Siddique pointed to the rising ethnonationalism and constant monitoring of personal data that characterize our world.

“There is a very interesting move back to majoritarianism, a very interesting move to almost fascism, a very interesting Orwellian control of information,” he said.

That people find their own ways to resist in every age, as Siddique asserts in his book, gives reason for hope. Those well-versed in the work of celebrated poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz will see this idea touched upon in the book’s title, taken from a poem Faiz wrote about being held as a political prisoner. The poem counteracts the grief of imprisonment with the knowledge that the powerful will ultimately lose power, while truth will survive. No matter how much power accumulates, it cannot “snuff out the moon”.

Listen to Osama Siddique read an excerpt from “The Book of Loathing” in Snuffing Out the Moon:

Photos from the event

Shehryar Nabi is a communications and advocacy coordinator at the Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives (IDEAS) and a communications associate at the Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR). You can follow him on Twitter @shehrnabi.