By Shehryar Nabi and Rabea Malik

It’s an intuitive notion: Educate people more, and they become less swayed by extremist ideologies. But the evidence on education and support for terrorism paints a more complicated picture.

Madiha Afzal, an assistant professor at the University of Maryland’s School of Public Policy, has mined through public opinion surveys to parse out where years of education matter, and where they don’t. She argues that providing education alone won’t be enough to reduce support for terrorism in Pakistan. Rather, schools should counter extremist narratives through curriculum reform.

In our latest expert conversation, Afzal explained her research and its policy implications to Rabea Malik, Research Fellow at the Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives (IDEAS).

You can listen to the interview here, or read the transcript below.

Audio of the interview:

Interview highlights:

[1:51] The conventional wisdom on the relationship between education and support for terrorism.

[4:54] How favorability and un-favorability toward terror groups, and non-responses to questions about terrorist groups (from polling data), correlate with education.

[6:20] When more education is correlated with negative views towards terrorism.

[7:56] Within terrorist organizations, are thought leaders educated and privileged, while the foot soldiers are uneducated and under-privileged?

[12:26] Examples of educational content that could foster extremism.

[17:34] We can’t say educational content causes support for terrorism, but rather it creates an environment that doesn’t challenge it enough.

[20:49] Why educational content that could foster extremism exists in the first place.

[22:57] Why people are resistant to reforming curricula.

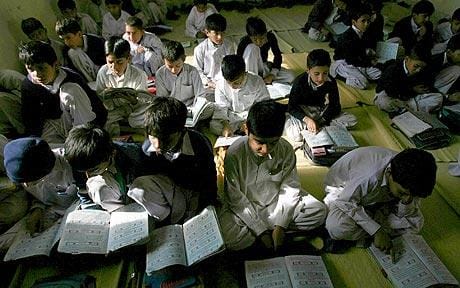

[24:38] Beyond educational content, is rote memorization and hierarchical culture adding to the problem?

[29:17] What are the prospects for future curriculum reform? Is this on the government’s agenda?

[This transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity].

Rabea Malik: Thank you Madiha for recording this podcast with us, I’ll begin by asking what got you interested in researching the relationship between education and support for terrorism?

Madiha Afzal: For a number of years I have been interested in looking at the roots of support for terrorism in Pakistan because of the poor security situation there. And the idea for looking at support for terrorism is because support matters in the Pakistani context. It legitimizes terror groups, it delegitimizes government action against these groups.

The way people have looked at this topic in general is to relate the support for terrorism to socio-demographics: years of education, income levels, and so on. And the way they’ve done this is correlated these variables with measures of support that are gleaned using polling data: What are your views towards the Taliban, what are your views towards Al-Qaeda, and so on.

The conventional wisdom that less education or less income are correlated with support for terrorism – according to these studies and even in the Pakistani context all of the work that had been done did not bear out the conventional wisdom. Essentially the evidence did not really say much, but it did not say that we cannot definitively say that less education or less income predicts support for terrorism.

I wanted to re-test this a little more carefully in the Pakistani context. The intuition is that years of education do matter. The fact that you’re going to school should matter for predicting attitudes. Yet in Pakistan we have very counter-intuitive aspects to this issue, like anecdotal support for terrorist groups for the Taliban from very educated people.

When I went ahead and looked at this using polling data from Pew which used data from the program on international policy attitudes, I found some really interesting results that then prompted me to start looking at this question in more detail. I realized it is not only years of education that matter, in fact they hide something. I wanted to look much more closely at curricula, and be able to say something more about what it is in the content of education that impacts attitudes. That’s when I started doing fieldwork in Pakistani schools and looked at textbooks and curricula and related that to attitudes of students.

If education and economic background do not necessarily determine support for terrorism, do they influence the role that someone plays in terrorism? Perhaps the underprivileged are more likely to commit acts, while the privileged are more likely to be thought leaders or organizers. For example, during the Mumbai terrorist attacks, the soldiers on the ground were commenting on all the expensive things that they saw in the hotel to a commander who could speak in English. So is this something we can be certain of given available evidence?

Yeah so let me actually briefly explain – they don’t influence support for terrorism, that’s what the data found up till my research. I found some interesting results that then prompted to look a little deeper so I’ll go through some of those results with you and then we can get to the question about the role someone plays in terrorism.

When polling data asks the question about people’s views towards the Taliban they can respond in one of three ways. They can say I have favorable views, they can say I have unfavorable views, or they choose not to respond. So a lot of this analysis that had found no effect essentially just chose to look at favorability along one dimension. But this is a three-dimensional issue if you look at favorability, un-favorability, and non-responses, which basically say that people choose not to respond either out of fear or perhaps because they don’t have enough information to respond.

What I found is if you split up the responses into these three dimensions, what you see is that favorability for terrorist groups does not vary much with education, that is true. It does go up slightly towards the middle levels of education which is basically secondary education: matric and intermediate education (Figure 1). So some secondary school, secondary school, and going to grades 11 and 12. That effect is not very strong, but it exists. That’s what prompted me to look at the secondary education further.

Figure 1: Pakistani views on the Pakistani Taliban, by education level, 2013

But the other interesting thing that you do find is that un-favorability is driven up with years of education because non-response rates go down. So basically, uneducated people will have low favorability, and also low un-favorability towards terror groups because many of them will just choose not to answer the question. But as you move forward in the years of education, essentially favorability has a bit of an upside down U, where it goes only up for secondary school a little bit and then comes down again.

But un-favorability – negative views towards terrorist groups – do increase and non-response rates do go down. So people become more confident in expressing their views and certainly their views do become more negative as education increases. That result is a little bit heartening and in some sense it shows you that part of what education is supposed to accomplish – make people more negative towards these groups – is being accomplished.

On the link between the role that someone plays and terrorism?

That’s a very interesting question and definitely an important angle with which to examine the question.

It makes logical sense: That the privileged are the ones who can think more about the grander schemes and the under-privileged are the foot soldiers, if you will. But I think that thinking just in general about what makes someone a terrorist regardless of whatever role they’re playing in terrorism, is not something that can be predicted by their education or their income quite simply. There’s usually something else that has gone on when somebody becomes a terrorist. There’s some sense of deep alienation, something flipping their head to the other side. So support for terrorism – while it may be linked to someone becoming a terrorist – is usually something that flips which basically means that the link is quite tenuous. I think these factors are usually much more important than social demographics.

But thinking a little bit more about the social demographics: Are people who are committing acts of terror, are they more likely to be more under-privileged relative to the general population that they are coming from? I think that’s sort of an important question there.

In the Pakistani context, there have been some studies (non-systematic) done on terrorists about a few years ago. But more recently, because the data on terrorists is pretty secretive – by the government, by the intelligence agencies – the data isn’t really out there for us to examine. What we have are reports of people like Saad Aziz who was by all accounts educated and privileged, who did go on to become a foot solider, right?

And then we also have the thought leaders, let’s say Mullah Omar who is not educated, not privileged. So we have those anecdotal accounts. We don’t really have a systematic understanding of these issues in Pakistan. That being said, I think even in the context of looking at recruits over the world, for recruits going to ISIS for instance, what the research is finding is that the foot soldiers aren’t necessarily those who are under-privileged. They’re usually either enrolled in college – we have examples of terrorists committing acts in the United States – we have Omar Mateen, we have the San Bernardino killer. Again, who are not necessarily under-privileged relative to the population that they come from but there is a deep sense of alienation and resentment. And again, something flipping in their head, which prompts them to go the other way.

You argue that anti-extremism efforts within education should focus on content in Pakistan’s curriculum, is that an correct assumption of what you’ve written?

Yes. In the public education system there’s some nuance to that, and I can elaborate on that. But I think in particular, in some of the work I’ve done more recently, I would argue that one of the ways to counter extremism in Pakistan is actually very simply to direct the efforts at madrasas that propagate extremist ideologies. So that is the direct link and the link with public education as I can explain in a little bit is a little bit more nuanced but it certainly is a place where anti-extremism efforts can be directed.

Can you give us some prominent examples of educational content that could influence people towards extremist and hateful ideologies?

Sure. Concentrating on public education or the government education system, where I’ve examined textbooks, it’s not that these textbooks have anything directly on terrorist groups. It’s not like they’re saying anything on current events and even the mentions on terrorism are literally numbered – one or two mentions of terrorism saying Pakistan’s playing a good role in the world in countering terrorism or Pakistan is a victim of terrorism. So there is nothing directly mentioning terrorist groups.

But what I argue influences people’s views, influences students’ views, are a number of structures in the Pakistani educational curricula. In particular I focus on the Pakistan Studies curriculum at the secondary level.

The first thing the curriculum starts out with is that the Pakistan ideology is Islam. Pakistan is created for Islam. And it goes on to say that Muslims are good, that non-Muslims are not, even though there’s some lip service to the view that minorities are equal. But essentially the content of the first few chapters where it’s explaining the creation of the country and Partition is that Muslims were good, Hindus were bad, and hence Pakistan needed to be created. There are references to jihad as an armed struggle against those of a different religion in the colonial context: fighting against the Sikhs, fighting against the British.

The references to India are pretty starkly negative, and Hindus before Partition: evil, calling them the enemy, and so on. There’s a sense that pervades the textbooks that the world is out to get Pakistan – when it came to 1971 the world was out to get Pakistan and in particular India conspired against Pakistan. And so what this kind of skeleton of a narrative that is set up – without any critical thinking or any views from the other side, any views on what might Indians think being put in there – what this sets up is a view of the world where a terrorist group comes out and says that we are only committing acts of terror because we want to purge Pakistan of foreign influences and western influences and impose Islam. And we are engaging in jihad against an infidel state to impose an Islamic system. A student who has not really understood the nuances of the Pakistan argument will hear that narrative coming from terrorists and say, “What’s wrong with that?”

It causes them to develop a narrative in their heads that when they encounter hateful propaganda or terrorist propaganda, they can’t counter that.

Can we say that this content has been causal for supporting terrorism, couldn’t support also be a reaction to global politics and foreign policy?

One thing I will say that it is not causal in the sense that many countries – Pakistan is not exclusive in having this narrative in its textbooks, this hyper-nationalist narrative, this negativity towards other countries, other religions. There examples in Israeli and Palestinian textbooks. There are plenty of examples in Indian textbooks, where there are examples that would coincide with the trends that we see in Pakistani textbooks.

It’s not causal for developing support for terrorism. One thing I will say is that despite the fact the majority of the country reads these textbooks, actual support for terrorism when you measure it is pretty low in these polls. Maybe we should have discussed that up front. But support for terrorism is on average around 10 to 15 percent of people who will say yes we have favorable views towards the Taliban. Of course their narratives are much more worrying, that’s one thing I argue about in my work.

But coming back to your question, we cannot say then that it’s causal in developing support for terrorism. However, given that Pakistan has this curriculum, and given that Pakistan has an environment where certain terrorist groups are able to propagate their narratives freely (there’s hate literature, there are magazines of these jihadist groups that you can buy literally in stores in some parts of Lahore, there are certainly mosques and madrasas where the narratives are being propagated sometimes during Friday prayers), there is a sense that if this curriculum did not exist – or if there were critical thinking in this system – then people could counter some of the narratives in that environment. So while curriculum may not be causal towards developing support towards terrorism, had the curriculum been different, people might have been able to counter some of the narratives that are out there.

I think it would be fair to say that an enabling environment is created, while not everybody chooses to act outside of the law or violently, there is an enabling environment that’s created, particularly in weak states or parts of the state that are weak.

Yeah absolutely.

Why do textbooks have this content in the first place and what prevents them from changing?

That’s a great question because why don’t we just engage in a curriculum reform? And a curriculum reform has been tried but essentially failed, though there have been some improvements at the margins.

The reason textbooks have this content in the first place is because this is a conscious effort by the Pakistani state to promote its narrative, a narrative that it considers to be of use to it. Essentially, textbooks weren’t always this way. Pakistan studies only became compulsory at the higher secondary levels and beyond around the late 1970s. This happened during Zia’s regime. General Zia – along with the help of Jamaat-e-Islami, inserted these notions of the Pakistan ideology. Not the two-nation theory, the two-nation theory already exists in these textbooks. But the fact that the Pakistan ideology is something identical to Islam was inserted into these textbooks in the late 70s, early 1980s.

Certainly the more negative content towards India was also inserted in the textbooks at that time. And the idea is that it serves Pakistan’s interests to be a country that identifies itself or defines in opposition to India. And that it defines itself on the basis of religion because that cements the Pakistani identity – an identity that the state felt was threatened in particular, post 1971 when East Pakistan seceded from it.

Essentially what prevents it from changing is that this is the conscious narrative of the Pakistani establishment. The establishment is pretty constant through military and civilian regimes, through various democratic governments.

But what prevents it from changing is also the fact that now an entire generation and more now have been schooled in this. When Musharraf came in and argued for curriculum reform in Pakistan and argued for the word “jihad” to be taken out of the curriculum – in fact the 2006 curriculum document does not have the word jihad to be included in the Pakistan Studies curriculum. Those suggestions to textbook writers were not taken into account because an entire generation of textbook writers or people working in the curriculum wing of textbook boards has been schooled in this curriculum. And in interviews they said, “We saw the document which says the word jihad should not be included but why not? We think it should be included.” So there’s pushback on various levels against this reform because people buy into the narrative.

In the conversation we discussed how the culture of learning is such that it discourages critical thinking and questioning. That’s linked to rote memorization and unquestioning acceptance of the narrative. Is this not a wider issue in society and a broader cultural characteristic? Is it fair to think that changing curricula and what is taught in schools bring change to society? Or does the sequencing need to be the other way around?

That’s a great question. I think you’re absolutely right – we are a culture that is very hierarchical, which tends to take things the way they’re presented to us, not to question people in positions of authority – they could be adults in your household or they could be your teachers. You’re taught not to question. I think part of what I argue the curriculum reform should be is a change in this culture.

I’ll give you some examples – even in Pakistan this kind of questioning does exist. I found in my research that public schools tend to have much more of this authoritative teacher culture whereas private – the low-cost private schools and non-profit schools – had a much more friendly teacher who was teaching in a more informal environment where students were asking him or her questions and engaging with them.

This may be, to some, a marginal difference compared to how teaching happens in other contexts. But I would argue at it makes a difference. So that’s one dimension: More teacher engagement, being able to ask questions, just being able to understand things logically in your head instead of memorizing them without any questions.

I think another example I would give, again in the Pakistani context is O-levels curricula. Compared to other contexts, I think the O-levels curriculum, while it encourages learning as opposed to a lot of questioning or going outside the box (I studied the Pakistan Studies textbooks for the O-levels curriculum) the textbooks themselves have so many differences with the Pakistan Studies textbooks at the matric level where they are presenting the other sides of the story. They are presenting things as not being black and white. So it’s not that those on the Muslim side, when it came to Partition, made no mistakes. In fact there were mistakes on both sides. Saying simple things like this can actually make a difference.

While it is true that on one hand it is a culture that discourages critical thinking. I think that a) loosening up the way things are taught – and again in Pakistan it does happen it’s only the government schools that are extremely strict – and b) trying to elaborate on and insert some nuances in the history of things in the curriculum can make a difference.

What do you think is the way forward, has there been any engagement at the policy level and realistically what kind of engagement can we envision?

That’s a tough question. I think when it comes to education in Pakistan there is a sense that curricula are on the back burner because Pakistan has so many issues when it comes to access to education. Because it’s often on the news: Issues of access to education first and then issues of learning at the elementary school, at the primary school level – learning math, learning English. It seems that the government is concentrating its efforts on those two issues. Policy does not seem to be concerned with looking at curricula as an important initiative.

There is a sense that people know this work is being done, it’s prominently written about in opinion articles that I’m sure are being read. The reports are disseminated. The government is certainly aware that scholars argue the curriculum is a problem in Pakistan.

To the extent that it would run in the face of the state’s narrative, which does not show any signs of changing, no I don’t think that it’s going to change substantially at any point soon. In fact, even when it comes to madrasas that are more extremist and hateful curricula being taught in extremist madrasas where the link is actually much more direct, that was actually part of the National Action Plan – to completely eliminate any sense of that. The work that’s been done by the government on that has been pretty haphazard. We see newspaper reports, “100 madrasas shut down here”, “50 parcels of hate material seized there”, but no evidence that the action against these things has been systematic.

In some sense, that should be the primary or first target by the government especially because the government itself acknowledged it and put it in the National Action Plan. But to the extent that public school curricula are not even on the government’s list of things that they say are going to be tackled anytime soon, I think any hope for that at this point is pretty muted.

Podcast edited and transcribed by Shehryar Nabi, a communications officer at the Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR) and the Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives (IDEAS).