Pakistan continues to face significant social and economic challenges. Provision of basic services such as health and education falls short of international standards, while women and the poor are often wholly excluded from accessing these services. At a time when the government is under pressure to demonstrate fiscal restraint, a strong public financial management system can help state institutions improve service delivery geared towards promoting both economic growth and poverty reduction.

A strong financial management system needs three things – aggregate fiscal discipline, strategic allocation and prioritisation, and operational efficiency in service delivery. Pakistan lacks on all three fronts. Its system of governance rests on weak financial planning and poor performance management coupled with a lack of accountability across all levels of government. This blog looks at some of these challenges and what the new government can do to fix these.

Snapshot of a typical budget: Allocation versus execution

In the case of Pakistan, public financing, especially for the social sector exhibits certain patterns that are pervasive and consistent across different levels of government. While these trends are easy to identify and understand, they may not be as easy to correct.

One such example is the case of the sectoral allocations, which largely go towards non-development spending, and overall disbursements remain dominated by salary expenditure. Development expenditure forms a minor chunk of the entire budget and is plagued by low utilisation of funds. This is in addition to the consistently low overall allocations towards the social sector as a share of the total budget. Pakistan spends less than one percent of total GDP on health and close to 2 percent on education.

Let’s take the example of the public education sector in Punjab. It employs the largest workforce (around 400,000 employees), runs more than 52,000 schools and enrols more than 12 million students in the province. Overall expenditure on education has grown by an average of 6 percent each year between 2010-11 and 2016-17 with an average spending of 17 percent of the total provincial budget. Within the same period, non-development budget remained above 90 percent. On the budget execution side, utilisation of non-development budget remained high (above 90 percent, touching 99 percent in 2012-13). However, utilization of non-salary and development budget in the same period remained low at an average of 65 and 50 percent respectively. This usually happens on account of two factors: lack of capacity to spend and/or delay in release of funds by the provincial governments.

Gaps in public financing are also aggravated by the sheer size of the sector. With over 50,000 spending units (schools), the government’s accounting system is not sophisticated enough to be linked with, or capable of monitoring, each of these units. At the same time improvements in learning outcomes are only marginal. There is often a faint link between budgetary allocations and overall development outcomes. Despite a substantial increase in the development budget for Punjab’s education sector, over 11 million children in the province still remain out of school.

The example of the education sector points to an obvious gap between what is being allocated, spent and achieved. The situation is similar in other sectors, which is why Punjab was only able to spend 65 percent of its PKR 635 billion development budget in 2018. Some of this can be attributed to the mode of service delivery. Service delivery propagated through the roadmap approach, for example, focuses on a limited set of indicators, at the cost of the bigger picture. There is thus little accountability within the system in terms of meeting the broader, more policy level sectoral objectives.

While Pakistan struggles with the scarcity of high-quality data, existing household surveys should enable policymakers to assess whether impact against certain fundamental indicators has been achieved. Why is then the budget delinked with outcomes?

Lack of sectoral strategies

Budget exercises unguided by an overarching sectoral strategy or policy lead to poor execution. Hence outcomes remain unchanged. Most interventions are ad-hoc and designed on political whims, rather than on actual demand or a sectoral plan. The use of ‘quick-win’, limited target roadmaps to implement service delivery leads to investment in areas that do not address the root cause of the sector’s underperformance. The school education roadmap focused on reducing out of school children at the primary level without allocating adequate resources to secondary education. This means an increase in drop-outs at a later stage i.e. more out of school children at the secondary level. Moreover, the budget making process is driven more by the available fiscal space and less by government priorities. Thus, the budget is invariably an incremental one.

Development overshadowed by political priorities

Elected politicians are held accountable on service delivery rather than on their ability to legislate or make new policies. They have little incentives to develop sectoral strategies, or deliver on the promises of sectoral strategies in the rare instance when they do exist. They want immediate results and hence focus on tangible development rather than softer interventions. Hence, development budgets are essentially determined by political priorities – be it recruiting 80,000 teachers or creating 2 million jobs. These priorities, regardless of whether they help achieve broader development goals or not, are met to gain political mileage. Subsequently, policy clarity is undermined as politicians end up battling with bureaucrats for space in the service delivery domain.

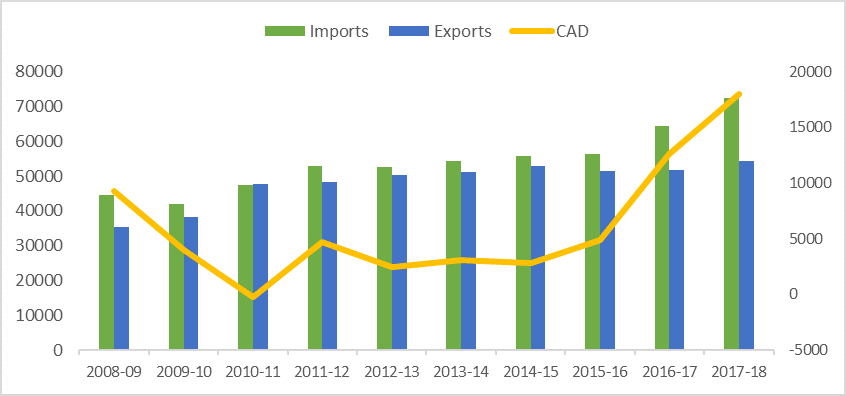

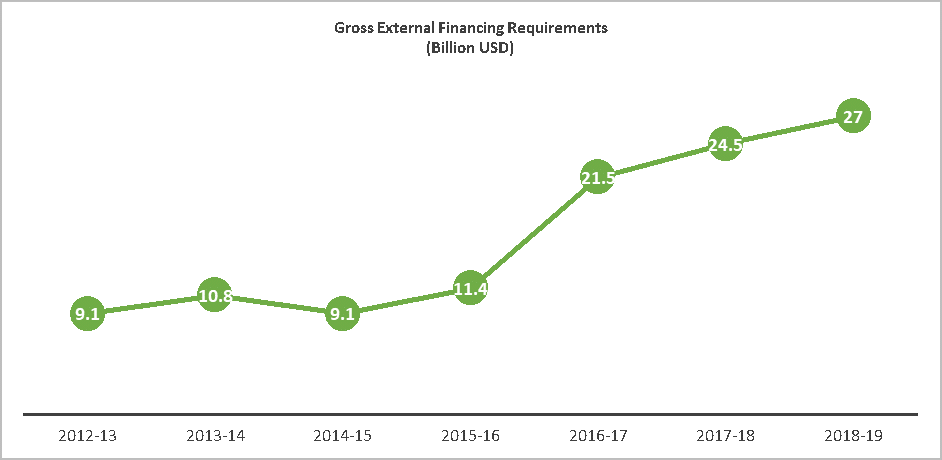

Overestimation of fiscal space

Pakistan does not practice aggregate fiscal discipline as its annual expenditures are seldom aligned to its revenues. Provinces forecast spending on the basis of projected revenue transfers from the federal government, which typically overestimates tax collection. Spending decisions are thus based on a fictitious number. This reduces the predictability of the budget, and leads to re-prioritisation which is both expensive and disruptive. Release of adequate funds becomes a concern and most often impacts development expenditures. Funds allocated towards infrastructure projects – the more visible and politically salient investments – are disbursed swiftly while softer interventions are put on the back-burner. There is little learning within the system and provinces continue to witness an annual budget shortfall year after year. The fiscal space for development thus keeps reducing.

What next?

The underlying mantra for improving financial planning is that it must be embedded in an understanding of the government’s key policies, priorities and capacity to deliver. It must also be forward looking and pre-emptive.

In the case of Pakistan, budgetary decisions are not informed by any sound analysis or sectoral view. Parliamentary debates on the budget turn into political tussles and seldom focus on the rationale behind stated allocations. The budget document itself is full of complex jargon, rendering it incomprehensible for parliamentarians. Moving forward, Pakistan can draw lessons from Korea, which has set up a national assembly budget office consisting of a team of chartered accountants, lawyers and economists to continuously inform parliament’s debate on the budget.

The new government appears fully empowered to take on the required restructuring of the budget by strengthening line departments that have typically left the responsibility of public financial management to the finance department. Line department must play a central role in providing direction to financial plans and setting milestones. These departments are also well placed to decide on the most efficient way to achieve these milestone, given limited capacity and resources.

Despite the fact that the new government has inherited a difficult fiscal situation, the solution does not lie in simply reducing expenditure but in fact in enhancing it at the right place. Government can and should focus on both improving public financial management practices at all tiers, and rationalising recurrent expenses without compromising drastically on development allocations.

Hina Shaikh is the Country Economist at the International Growth Centre (IGC).