Women in the developing world face an array of vulnerabilities and are at a relative disadvantage when compared to men. In Pakistan for example, they are less likely to receive vital information on health safety, have lower levels of education, and are less likely to own a mobile phone or have internet access. In the context of a pandemic like COVID-19, these disparities only exacerbate with a larger proportion of women being pushed into extreme poverty than men. This is due to a higher probability of employment in the informal sector and lower wages, which are negatively affected in a health-care emergency. Moreover, women often have a higher share of domestic responsibilities which have only increased during the pandemic. Policy needs to tackle this depravation and should be formulated in a way that stems information asymmetries and ensures the provision of essential services so that women are looked after both financially and otherwise.

Multidimensional gender disparities have worsened globally during the COVID-19 pandemic. These are further amplified in regions of high fragility, conflict and poverty. Women face a disproportionate impact of such external shocks as they are more exposed to health risks and loss of income. With social confinement measures in place, women also take on a larger share of unpaid care work and become more likely to face gender-based violence. Even when resources and institutional capacity is limited, an effective response to the COVID-19 pandemic needs to focus on safeguarding and representing everyone’s interests equitably while ensuring that women remain at the centre of such efforts.

This pandemic has exposed and exacerbated deep-rooted gender inequalities within Pakistan, just as in many other countries. Pakistan already ranks low on the global gender parity index (151 out of 153 countries), performing poorly across most parameters of gender equality. COVID-19 poses a significant risk to any development gains (even marginal) that women have made in the past decade. Despite this, Pakistani women have remained at the forefront of all efforts to fight the pandemic. More than three-fourths of all employees in the country’s health sector are women, while the role they perform as caregivers within households has become of immense importance due to the current arrangement of work-from-home and home-school children.

Are men more prone to contracting the virus?

In Pakistan, it appears that more men than women have been affected by COVID-19 as more than 70% of all positive cases were reported amongst men. This is contrary to WHO figures that show a relatively even distribution of the case load across both genders. In Pakistan, higher infection amongst men could possibly be due to their more active engagement in the public space as labour force participation rate for men is much higher at 68% compared to 21% for women, far lower than countries with similar income levels. Despite a steady increase in the past decade and a half from a low of 13.7% in 2000, these rates remain the lowest in the world, second only to Afghanistan’s.

However, it is important to note that comparatively lower level of positive cases amongst women may be a result of lower rates of testing for women rather than a lower rate of infection due to reduced mobility. Regardless, the risk of spreading the disease in-doors still remains high while intra-household dynamics may be preventing women from making independent decisions regarding their health, including accessing healthcare.

Moreover, women in Pakistan are less likely to receive information about COVID-19 for reasons such as limited access to the internet, limited cell phone ownership, and relatively lower levels of education. Women in Pakistan are 37% less likely than men to own a mobile phone or have internet access. Limited access to such necessary information puts not only women, but also their families at higher risk of contagion. In addition, it also limits their access to essential services such as helplines or online platforms in case of health or financial crisis, or incidence of violence.

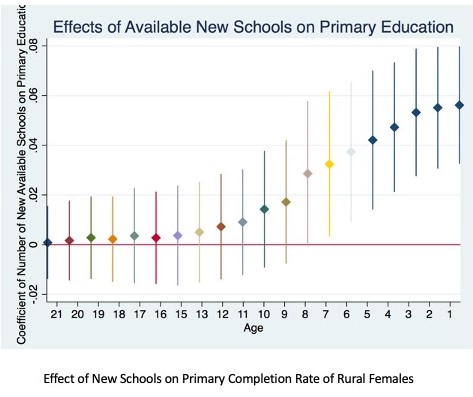

Economic vulnerability

In addition to a substantial rise in overall poverty due to the pandemic, more women than men are likely to be pushed into extreme poverty as they are often less prepared than men to bear the economic impact of such shocks. They typically earn less than men, reporting wages lower by at least 67% compared to men. Women are also more inclined to work in the informal sector with less secure jobs compared to the formal sector. They form 74% of the informal economy, although only 3% of the employed women work in the informal sector while more than half work as contributing family workers. With reduced economic activity due to COVID-19, women remain more vulnerable to layoffs and loss of livelihoods. Girls education is also suffering. When schools reopened in September 2020, approximately 13 million children remained unenrolled, of which 60% have been girls.

Women are essential to the subcontracting system, especially for small enterprises operating out of home-based or informal workshops. Of the 12 million home-based workers in Pakistan, 80% are estimated to be women. Many women employed by small or medium businesses and/or working as domestic workers have faced pay cuts or layoffs due to a slowdown in economic activity and inability of employers to continue paying wages in the face of COVID-19. Pakistan’s women-owned microenterprises, often smaller than men-owned, have been 8% more likely to lose their entire revenue due to the on-going pandemic.

Teaching is a common profession for many working women in Pakistan. Due to indefinite school closures, staff and teachers of many private schools have received substantial cuts in their salaries or faced layoffs as owners try to stay afloat. Getting to work remains a major challenge for most Pakistani women. As smart, localised and intermittent lockdowns continue, hindered mobility and increased absenteeism may also result in loss of employment for many women who lack access to independent means of transportation.

Domestic violence

The onslaught of the pandemic has also brought with it increased burden of domestic violence; a direct association has been observed between number of cases of domestic violence and COVID-19. Government statistics show a 25% increase in incidents of domestic violence during the lockdown just across eastern Punjab alone. Between January and December 2020, the country reported 2,297 cases of violence against women based on data collected from 25 districts (according to a recent report by the Aurat Foundation). At the peak of the pandemic in July, cases of violence against women were highest and rose again with the resurgence of COVID-19 in September last year.

Unpaid care work

In Pakistan, not only do women earn less than men (when their work does not go unrecognised and unremunerated), but they are also more ‘time-poor’. Accounting for both unpaid care and paid work, women work thrice as many hours as men on average globally, and up to 10 times more in Pakistan. There is excessive drudgery and time burden of unpaid care for women. During the lockdown, this disproportionate burden of household work increased even further. As families stayed home all day, basic domestic responsibilities – such as cooking and cleaning – increased as did the burden of home-schooling. An unequal responsibility for unpaid care work continues to constrain women’s mobility and time, impeding their access to education, healthcare, skills development, technology and financial services.

Conclusion

A complete COVID-19 response strategy must focus on women and on enabling them to better handle this crisis. Gender disaggregated data is critical to help inform the response to COVID-19 that is sensitive to the realities of women. Data disaggregated by gender that is publicly available will also encourage the public and private sectors to come up with appropriate solutions. With schools beginning to gradually reopen, the government should make an extra effort in ensuring girls return to schools. Information campaigns can be accompanied with monetary incentives to encourage regular attendance of girls, especially in middle and high school as they are most likely to drop out. Overall, women and girls can suffer decades-long impact if targeted effort is not made towards a gender-equitable COVID-19 response. Continued provision of essential services (family planning, maternal health care, and protection against gender-based violence) is critical.

This article originally appeared on the International Growth Centre’s (IGC) website here. This article is part of IGC’s International Women’s Day series.

Hina Shaikh is a Country Economist for the IGC in Pakistan.