This blog builds on three presentations from a webinar cohosted by CGD and the Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR) on September 22, 2020. You can view the webinar here.

When the COVID-19 pandemic reached Pakistan in late February, it was expected to hit the country badly. The concern was that with poor health and nutrition indicators and the fiscal restraints imposed by an ongoing International Monetary Fund (IMF) stabilization program, Pakistan would be unprepared to respond. The health fears were stoked further in late May when Pakistan’s R0 value (a measure of contagious disease that indicates an epidemic for values greater than one) surpassed two and the positivity ratio (the percentage of those tested found to be infected) peaked at 22 percent in mid-June.

When the COVID-19 pandemic reached Pakistan in late February, it was expected to hit the country badly. The concern was that with poor health and nutrition indicators and the fiscal restraints imposed by an ongoing International Monetary Fund (IMF) stabilization program, Pakistan would be unprepared to respond. The health fears were stoked further in late May when Pakistan’s R0 value (a measure of contagious disease that indicates an epidemic for values greater than one) surpassed two and the positivity ratio (the percentage of those tested found to be infected) peaked at 22 percent in mid-June.

In response, Pakistan intensified its lockdown. Despite the limitations, the government also rolled out a spate of health, income support, and business financing interventions to mitigate the economic hardships. By mid-August, the virus was under control, as seen in the sharp decline in daily cases and deaths. Civil unrest, feared in the early stages when the country faced a generalized lockdown and a severe income shock to low-income urban households (nearly half the population), did not materialize. Importantly, despite the fiscally demanding coping interventions, Pakistan remains on the pre-COVID-19 macro-stabilization trajectory.

COVID-19, of course, is not behind us—it may return and may again severely test the government’s management capacity. To prepare for this, the lessons learnt from coping with the crisis as it has unfolded thus far will be valuable both to Pakistan to manage a possible second wave, as well as to other countries.

Assets on the eve of the crisis

The country’s poor health outcomes are reflective of the underlying inadequate health infrastructure. The 2010 devolution of health services to the provinces would also pose coordination challenges. Even more worrisome was the widely held perception of a weak implementation capacity enfeebled further by the tight fiscal space. On the assets side of the balance sheet, there was a world-class digital highway to deliver cash support to the poor, the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP) and widespread mobile phone and internet connectivity. Large and regular household and business surveys had created data banks that would facilitate micro-lockdowns. Importantly, while there were misgivings about governance in general, the government and civil society had a track record of meeting catastrophic emergencies with resilience and order (for example, the 2005 earthquake, floods in 2010, and the 2014 military operation against terrorists). Pakistan Center for philanthropy estimates that Pakistanis give 1.2 percent of GDP in charity which equals charity contributions in the United Kingdom (1.3 percent of GDP) and Canada (1.2 percent of GDP), and around twice India’s.

Although fiscal policy was tight in March, the overall macroeconomic position had improved over the previous eight months. The government had eliminated the current account deficit of US$2 billion a month inherited from the previous government. Reserves were building up and the previous two quarters’ fiscal adjustment had resulted in a primary surplus. Significantly, the government was gaining confidence in its economic management capabilities that would be important in pumping much needed liquidity into the economy to cope with COVID-19.

With these assets, the government embarked on a three-pronged program focusing on virus containment, cash transfers, and business support.

Virus containment

Given the uncertainty surrounding the spread and duration of the virus and the fiscal realities, it was decided early on that the containment strategy would strike the right balance between lives and livelihood.

The next step, learning from previous emergencies, was to set up a centralized National Coordination Center (NCC) chaired by the prime minister, with all provincial chief ministers and key federal ministers as members to facilitate coordination. To operationalize decisions of the NCC, a National Command and Operational Center (NCOC) was established in late March, chaired by the minister for planning and with representation of military and federal agencies. NCOC met daily, tracked the virus round the clock, and implemented containment measures.

Virus containment was built on South Korea’s model of testing, tracking, and quarantine. It rested on two platforms: at the grassroots level, thousands of personnel of provincial health departments and civil administration services were mobilized; and a technology platform was set up to identify positive cases and track them to isolate hot spots. The objective was to move from broad to micro lockdowns. By mid-June, 5 percent of the country’s 212 million people was locked down, capturing 43 percent of total active cases, the threshold for tolerable economic disruption.

Several measures show the impact of the strategy: R0 fell from greater than two in mid-May to under one (indicating that the disease was dying down) at end-June (the country’s contact tracing factor of 1 to 15 meets world standards); the positivity ratio fell from 22 percent in mid-June to under 2 percent in mid-August; daily deaths fell from 144 to single digits; compared to Pakistan, mortality per capita in India is a multiple of 17, a multiple of 46 in Iran, and a multiple of 5.5 in Bangladesh. Correlates such as hospitalization and utilization of PPE (all monitored by NCOC) corroborate these trends.

The crisis response underscores the importance of reliable health data. Preparing for a possible second round, several data shortcomings need to be addressed. These include lack of publicly available data on death, widespread diseases such as tuberculosis to assess collateral damage, and public attitudes towards vaccination. COVID-19 testing also needs to be ramped up. Good data will help assess the impact of interventions given that demographic features may have contributed to the low incidence of infections, such as the youth of the population, reduced mobility, and exposure to other diseases—factors that might have strengthened immunity.

Cash transfer

Ehsaas (Pakistan’s social protection program that incorporates the BISP) was assigned the responsibility of providing cash support to poor households to cope with the economic shock of the crisis. Ehsaas data shows that 24 million daily wage earners support 160 million people—some two-thirds of Pakistan’s population—and there was widespread anecdotal evidence of huge suffering because of the lockdown-associated income shock.

The macroeconomic discipline leading up to March created the fiscal space to cope with the income shock. The government allocated Rs 144 billion for income support to 16.9 million families ($75 per family over two months), later increased to Rs 200 billion (0.48 percent of GDP). Three categories of recipients were identified. The digital highway to transfer cash to category 1 families (4.5 million with asset score of 16.17 identified in the BISP program) already existed. Utilizing available data, it was extended to category 2 (4 million families with asset score between 16.16 and 26—the asset score measures the value of assets a household owns).

Identifying category 3 was more demanding. Endemic poverty in Pakistan is largely rural. COVID-19-related income shocks were mainly in the urban areas so the BISP digital platform had to be extended to include deserving urban households. An SMS campaign was launched to capture urban wage earners suffering the income shock; 139 million messages were received of which 66 million were unique as identified via the National Database & Registration Authority (NADRA) card. These were then cross checked with other data linked to the card, such as large expenses, tax payments, and so on. Due diligence by union council (local government) representatives in the locked down areas (working closely with NCOC), a time-consuming process to be certain, helped identify an additional 3.5 million families.

Ehsaas has responded well in providing income support during the crisis. Overall, the program has a good conversion rate measured as the ratio of the amount withdrawn to the amount disbursed to the banks for payments to beneficiaries. Payments to category 3 is a challenge because of the complex verification process. The capacity to carry out rapid assessments of continued COVID-19 related disruption will need to be developed and the digital highway of cash transfers to the urban poor, currently not captured systematically on Ehsaas platforms, will need to be constructed and evaluated for impact.

Ijaz Nabi is the Country Director at IGC Pakistan and Chairperson at CDPR. He is also a Non-Resident Fellow at the Center for Global Development (CGD) and this article originally appeared on the CGD website here.

For more information, watch the full session of the webinar on which this blog is based.

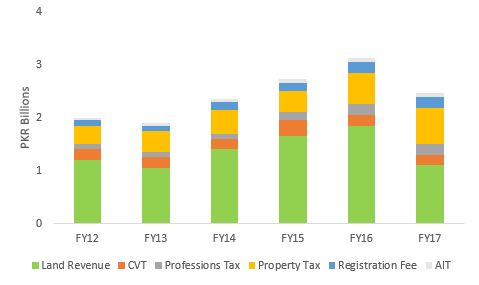

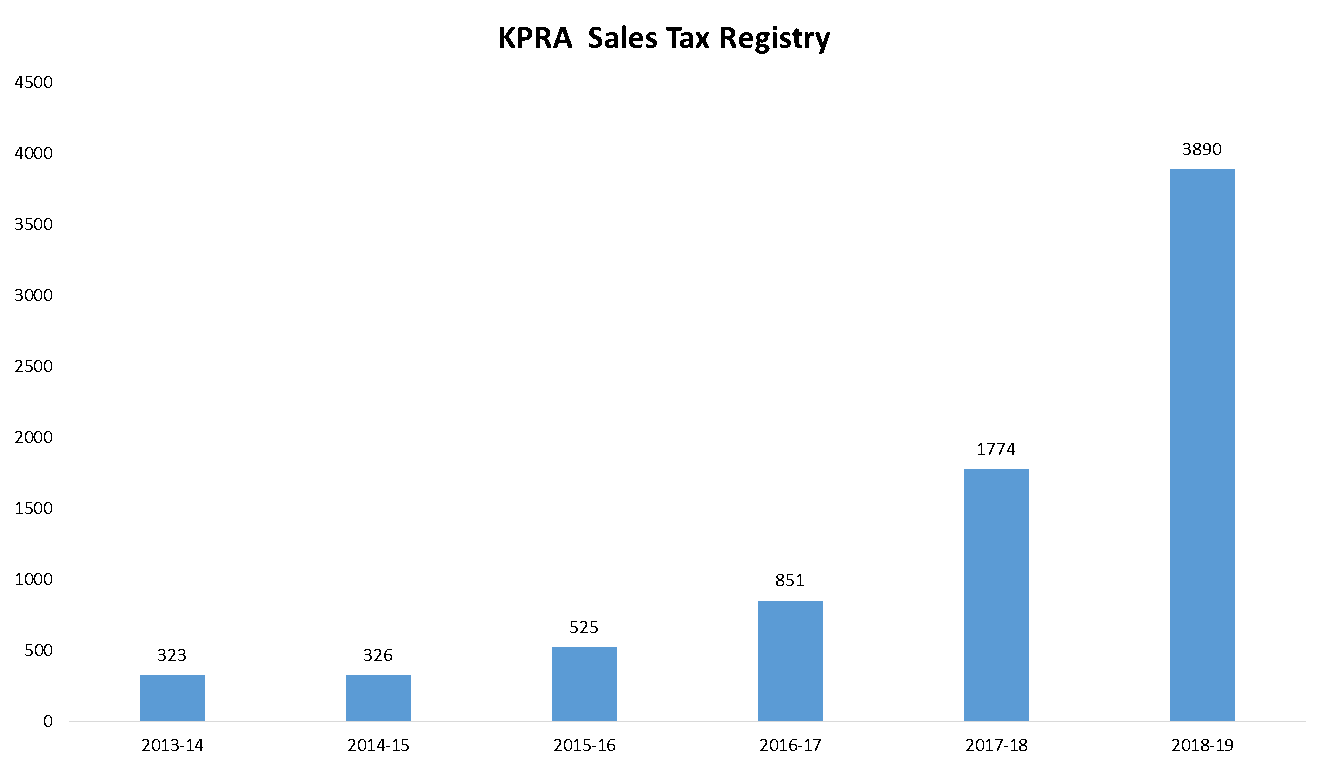

Source: KPRA

Source: KPRA