The Centre of Economic Research in Pakistan (CERP) with support of the International Growth Centre (IGC) is conducting a series of projects aimed to understand the impact of women’s mobility on their labour market integration.

Despite more women entering Pakistan’s labor force, its workplaces remain highly male dominated. According to the latest labor force survey, between 2008 and 2010, female labor force participation rate has increased from 19% to 22.5%. However, this is still much lower compared to the world average (39.2% in 2018 as per the World Bank Data).

Some of the reasons that prevent women from entering the labor market include unfavourable social norms, restrictions on mobility, gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, safety concerns, and all-consuming household duties. However, there is little in-depth scientific research to understand why there are so few women entering the labor force.

A team of researchers based at the Center for Economic Research Pakistan (CERP) and with the support of the International Growth Center (IGC) set up an employment facilitation platform – Job Talash (search) (earlier called Job Asaan (easy)) to understand the dynamics of the female labor market in one of Pakistan’s major metropolitan centers, Lahore. Survey data gathered from female subscribers of the employment facilitation service operating only in Lahore at the moment as well as from firms, suggests that there is both a willingness on the part of firms to hire more women and a desire expressed by women to enter the labor force if they find a suitable job. Yet the labor market does not reflect these desires.

A geographically representative survey of households provided two key pieces of information – how many people are looking to enter the labor force and, relatedly, how many of them were willing to sign up for our employment facilitation service.

The team called all individuals who had expressed an interest in the household survey to sign them up for Job Talash and assisted them in creating a resume for each person based on the details requested from them (educational qualifications, details of work experience) and matched them to jobs (job interests). This information has allowed the researchers to match the subscribers to jobs posted by firms, who were enrolled through a similar exercise covering all areas of Lahore. Apart from listing job advertisements, the firms also participated in a detailed survey about their hiring patterns which helped the team study the demand side of the labor market.

With an active platform of jobseekers and firms, the team was able to capture real-time application behavior, giving them a unique insight into how the subscribers operate in the labor market and their revealed preferences about job seeking activity through application behavior rather than self-reported information. The researchers were able to record their response, or non-response, to each job match they received through the portal.

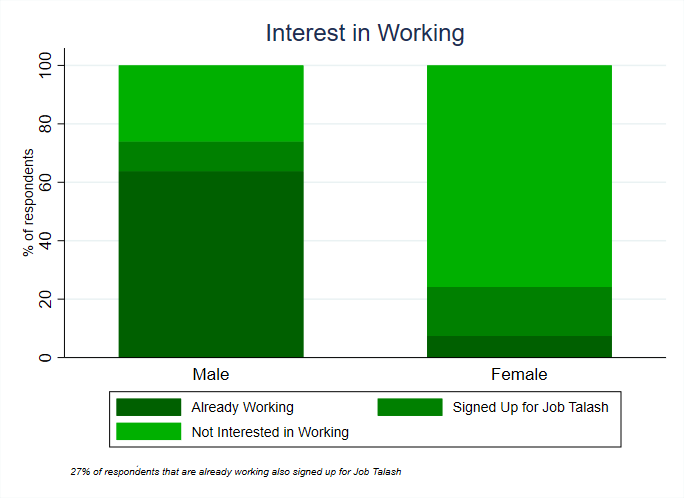

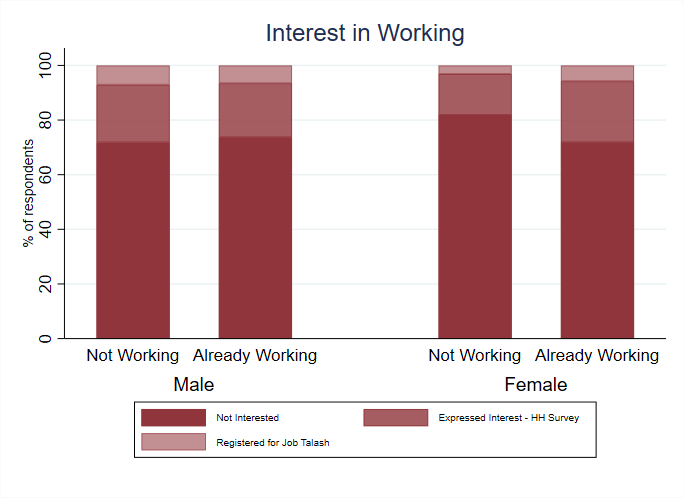

One might think women simply do not want to consider working due to conservative social norms that constrain them from taking any job and/ or exclusively assigned responsibilities of dependent care work and household duties. Yet almost 20% of the women part of the household survey, currently not working, expressed an interest in working (Figure 1). Female labor force participation rate can more than double if these women take up jobs. Around 36% of this group have high school education or higher (12+ years of education) and 64% have a lower than high school education level. Of these, 18% went on to take the time to complete the in-depth sign up process for the job search service (Figure 2).

Despite willingness to work, supply of female labour has remained largely untapped – why?

Figure 1: Interest in working by gender

Figure 2: Interest in working by gender and current employment status

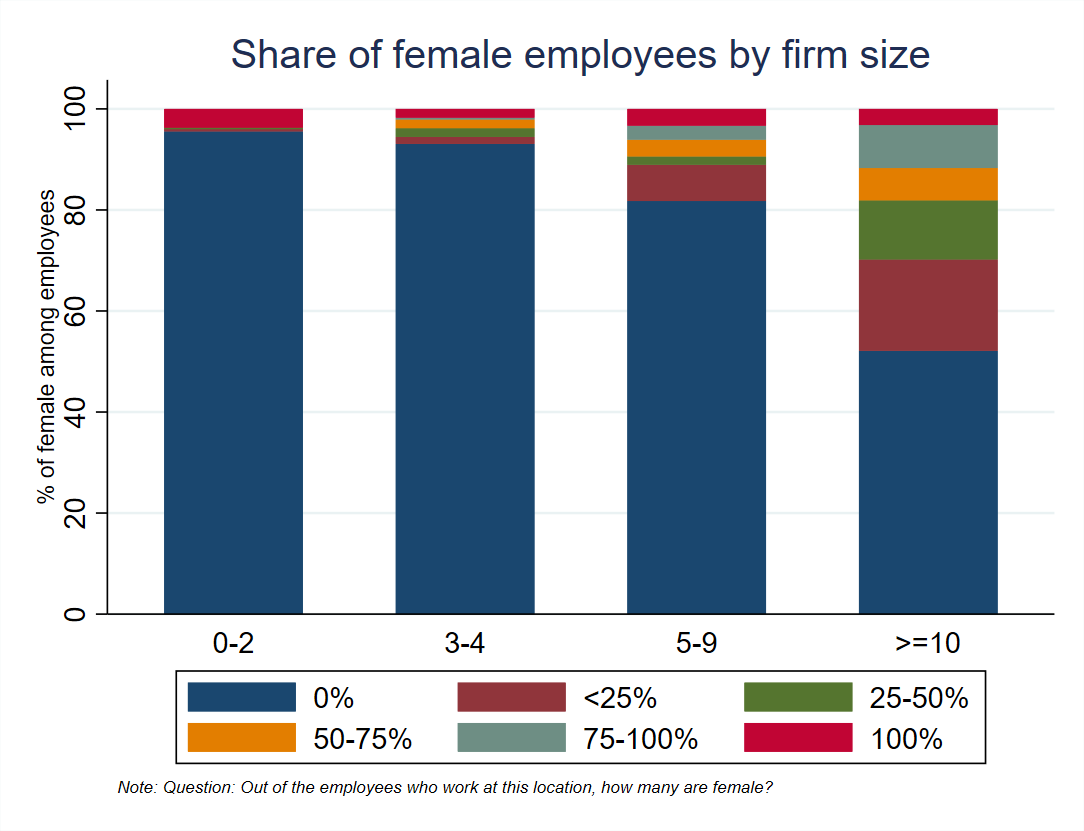

Perhaps the constraint is on the firm side, in that employers might not want to hire women due to concerns about their competing family pressures, or simply due to discriminatory preferences. Most firms in the representative sample of Lahore do not currently employ any women, although women are much better represented in larger firms (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Share of female employees by firm size

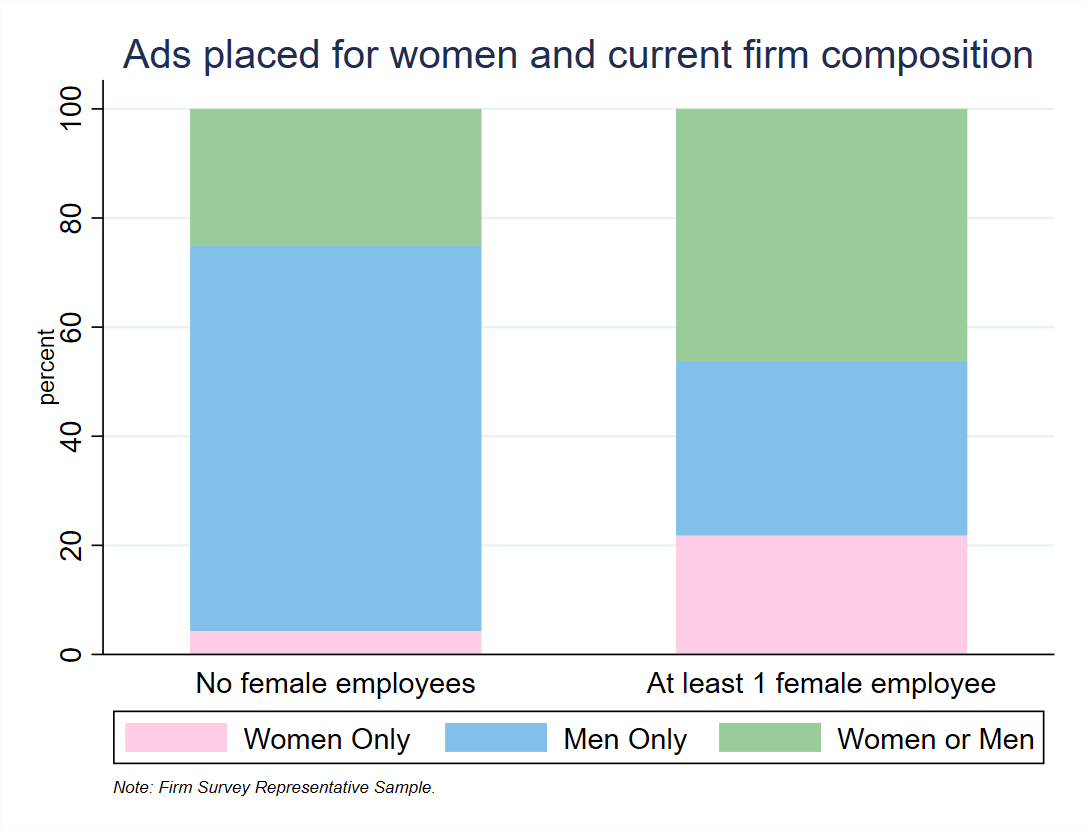

However, firms’ job postings with the service show that many companies are willing to hire more women. Figure 4 shows that firms with at least one female employee ask to receive applications from female candidates for at least 65% of their job openings. Even many firms that currently employ no women are willing to consider them – around 30% of the jobs posted by firms with zero female employees ask to see resumes from female candidates.

Figure 4: Job advertisements posted for women and current firm gender composition

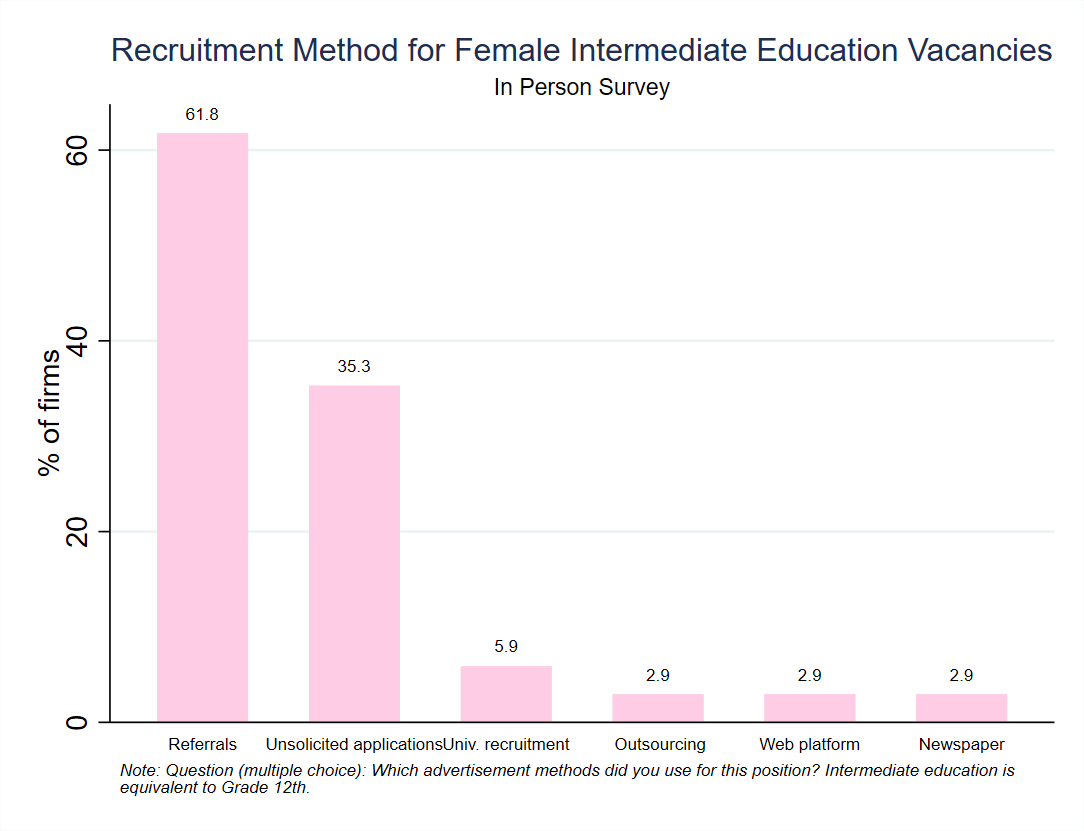

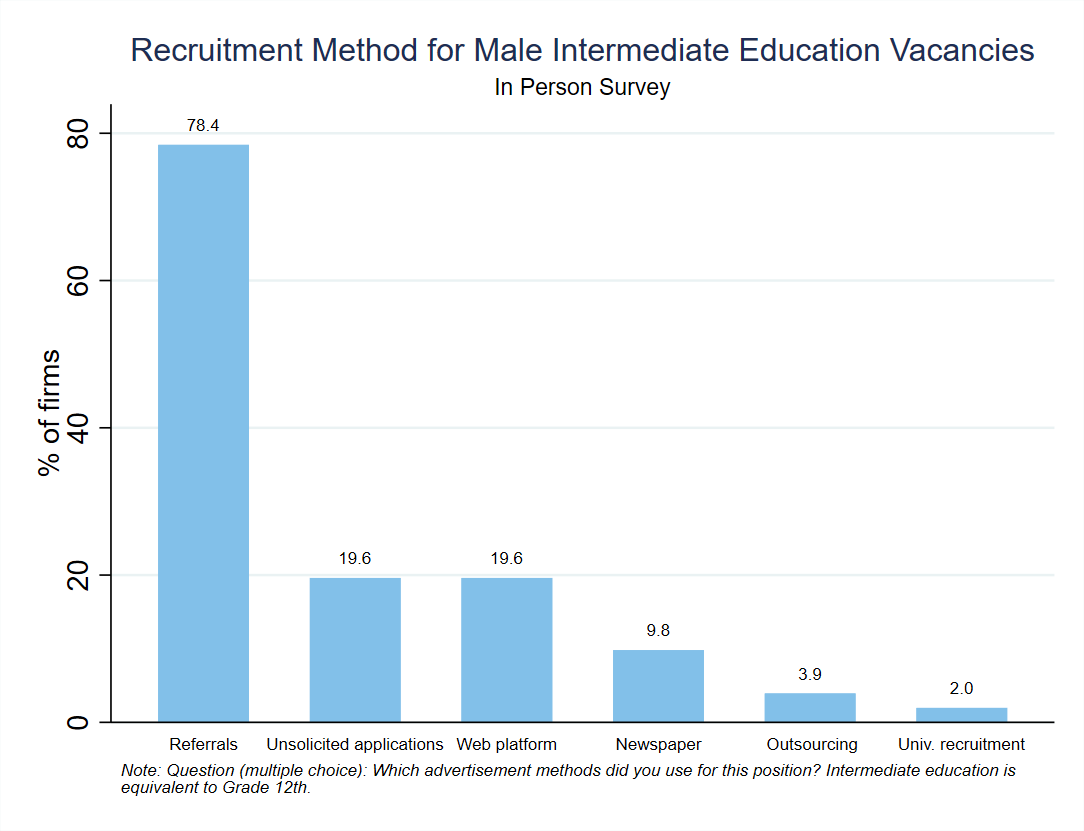

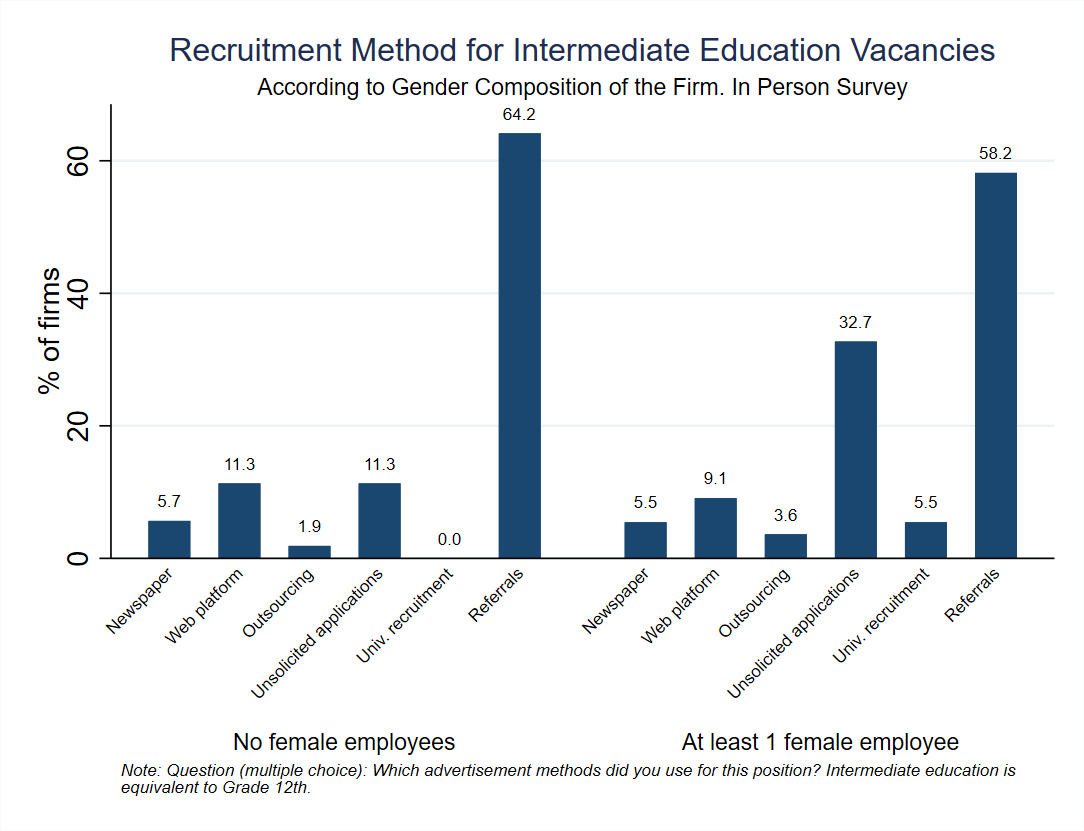

If firms are willing to consider female candidates, and women are willing to work, why does the proportion of women in these firms remain so low? One potential reason for this is referrals that play a significant role in recruitment – it is by far the most common hiring method, even for high-end jobs (Figure 5 & 6).

Figure 5: Recruitment methods for female high-end filled vacancies

Figure 6: Recruitment methods for male high-end filled vacancies

Women lose out in referral-based employment because of societal barriers and a lack of access to the kind of referrals men might benefit from. Beaman et al (2015), in their experiment designed around a recruitment drive of real jobs, found that qualified women tend not to be referred by networks. The study’s data shows that women are hired through referrals less frequently than men and are hired because they submitted unsolicited applications more frequently than men. Firms with no female employees hire through referrals at a greater rate than firms with at least one female employee (Figure 7).

By providing free hiring services through Job Talash and gathering survey data on all hiring, the team allows firms to hire women or men from outside their social networks, and observe whether they choose to do so or not. This provides a chance to test whether a range of interventions change that decision, and whether it expands opportunities for women.

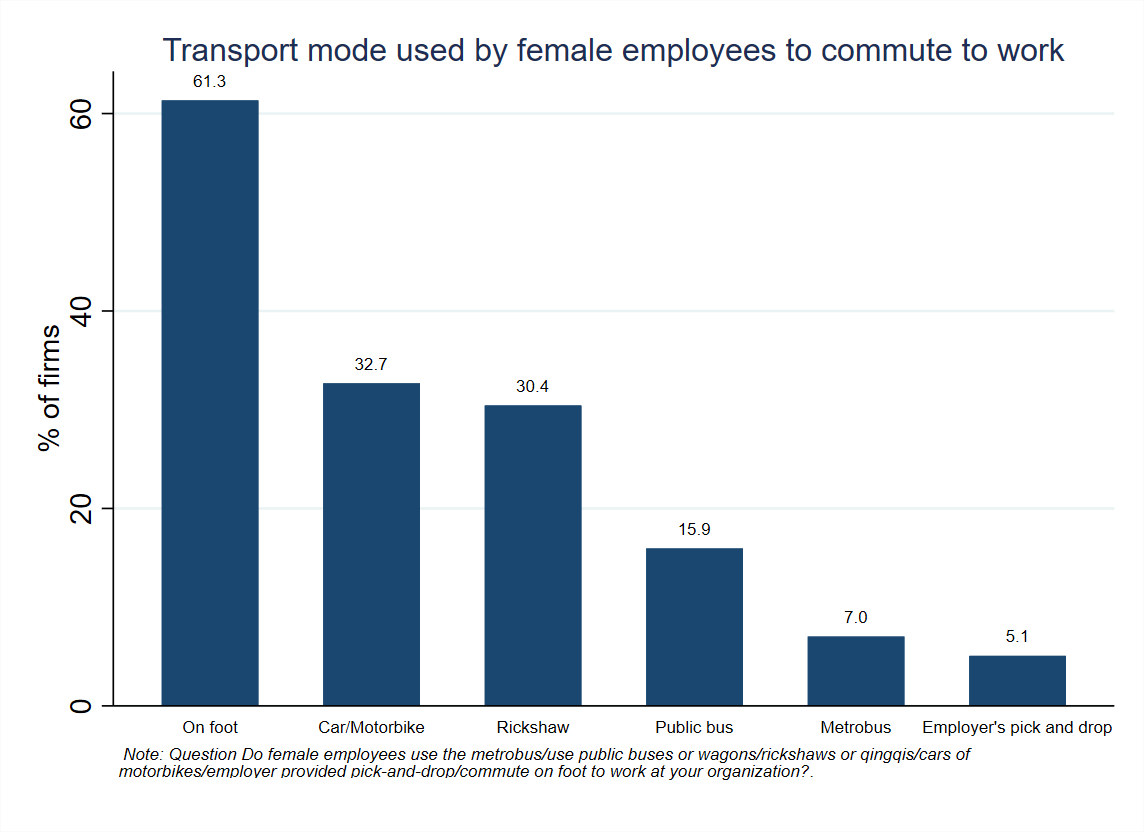

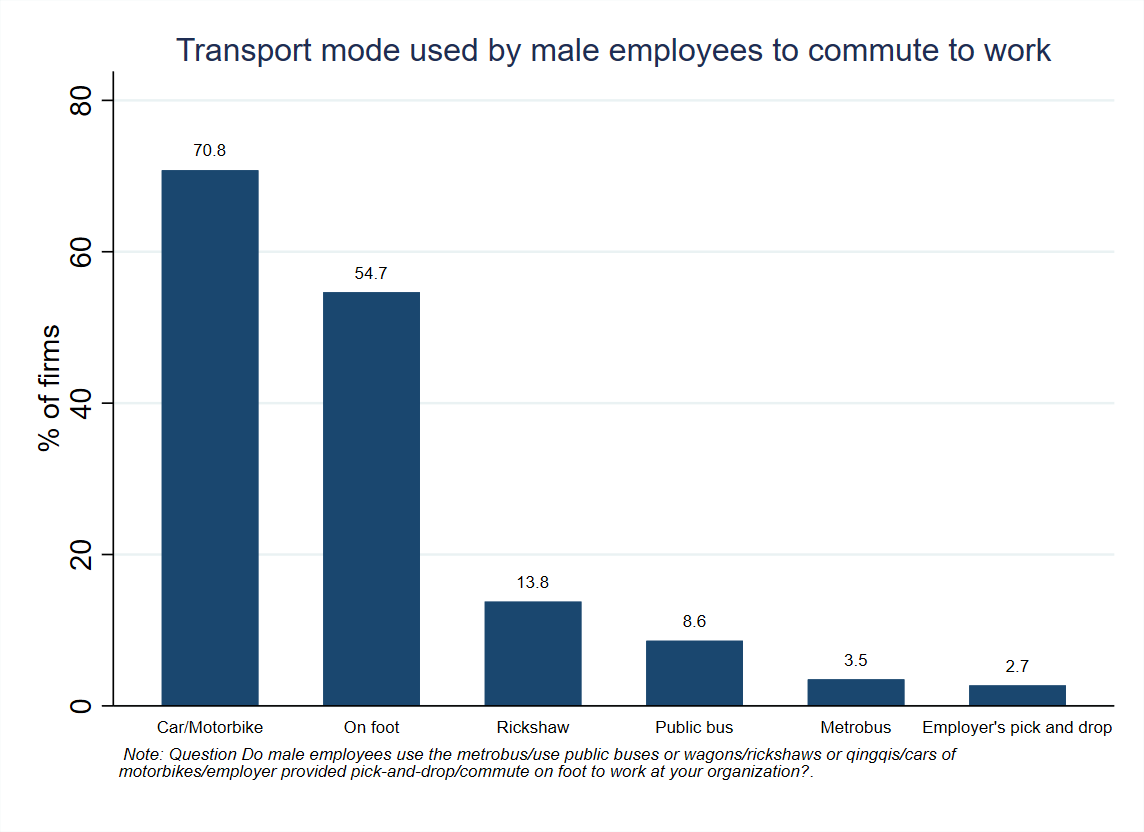

When asked how firms’ employees commute to work, there is a significant differences in responses for female and male employees. Firms were asked whether females and males use a number of different transport modes. Figure 8 (a) and (b) indicate that women are more likely to walk or take public transportation compared to men, of which 71% commute using their own car or motorbike.

Figure 8 (a): Firms response on their employees’ transport mode for commute

Figure 8 (b): Firms response on their employees’ transport mode for commute

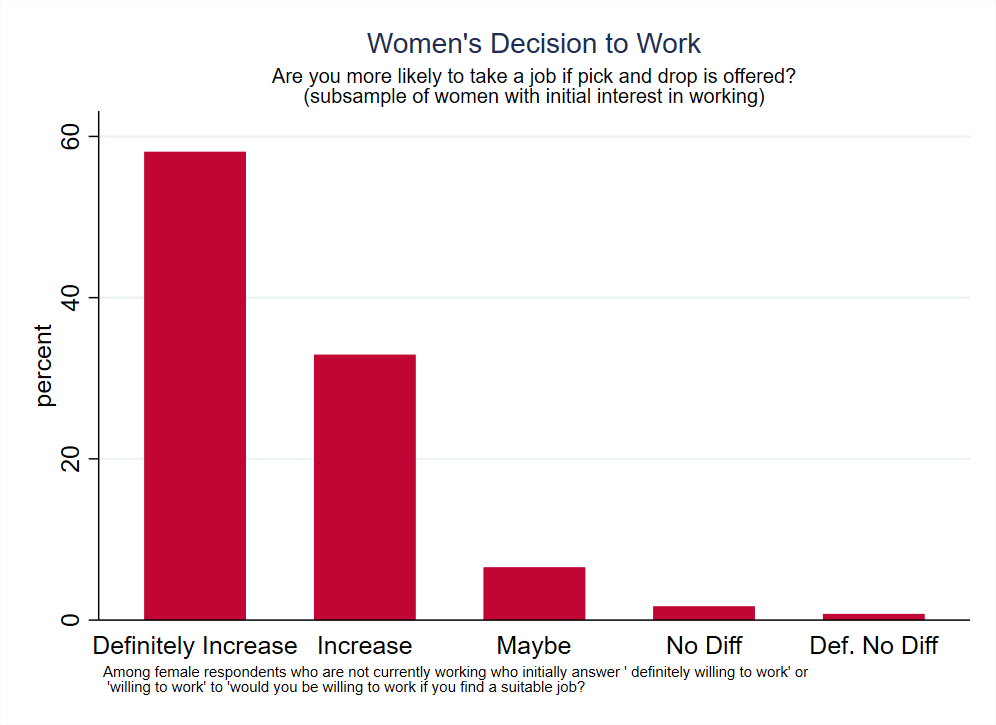

Approximately 90% of women surveyed who were willing to enter the labor force said they would be more likely to work if safe and reliable transportation, like employer pick-and-drop, was provided (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Impact of safe transport on decision to work among women

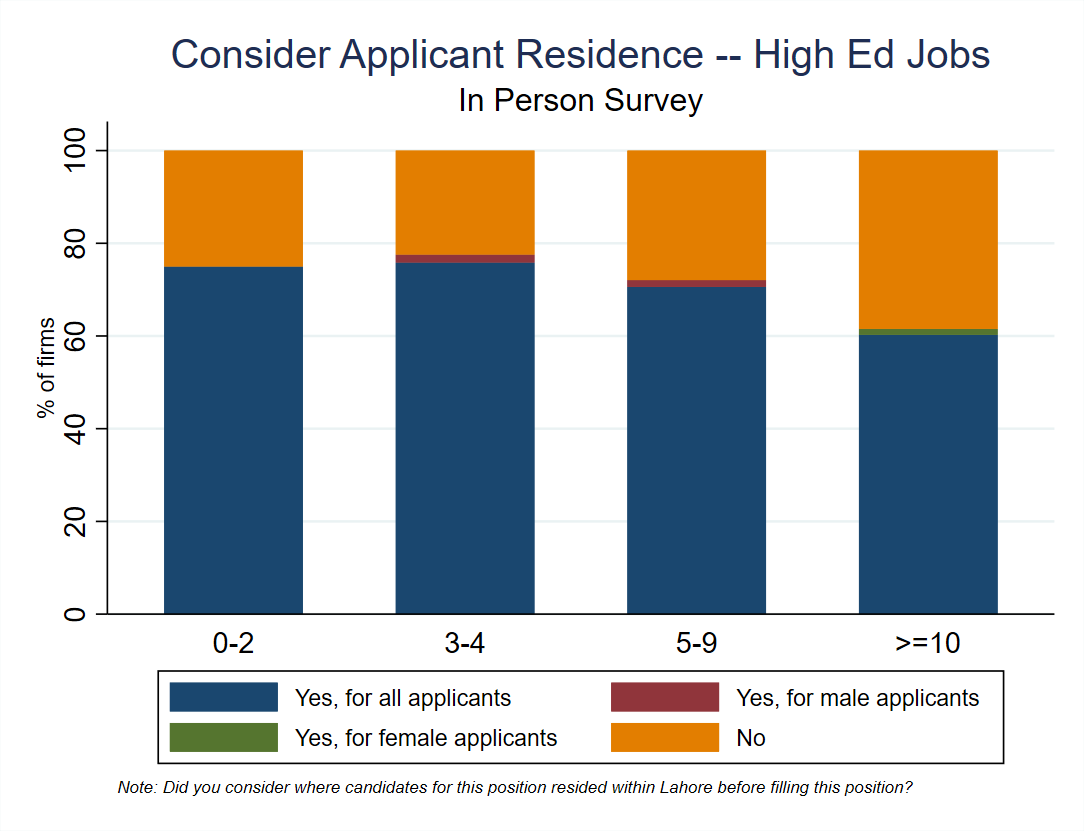

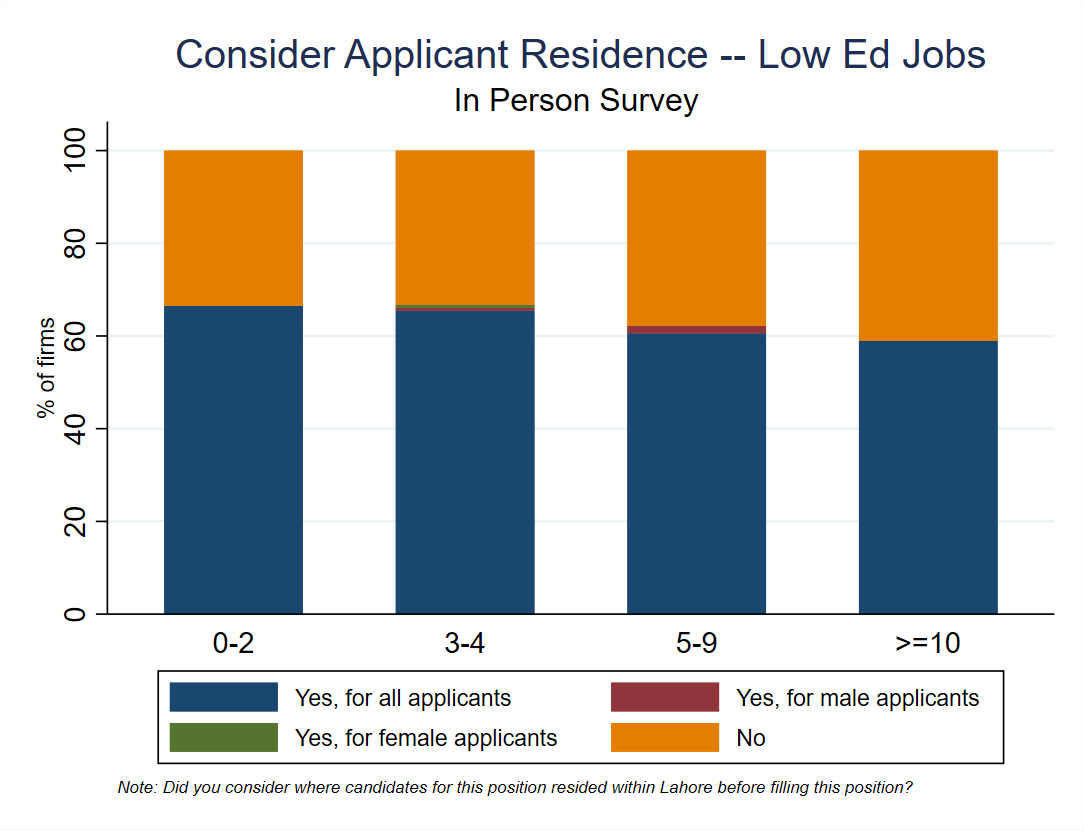

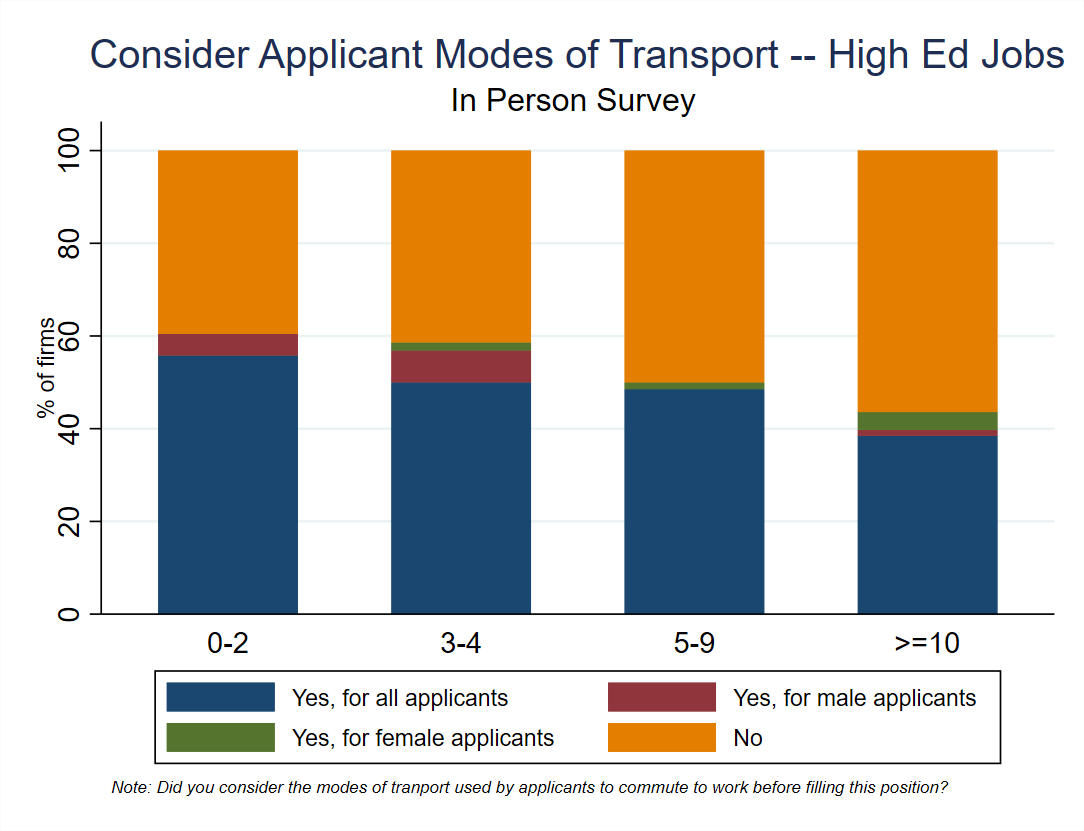

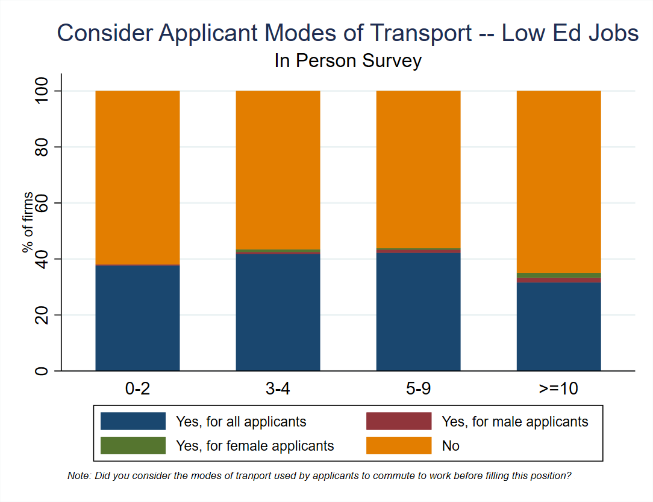

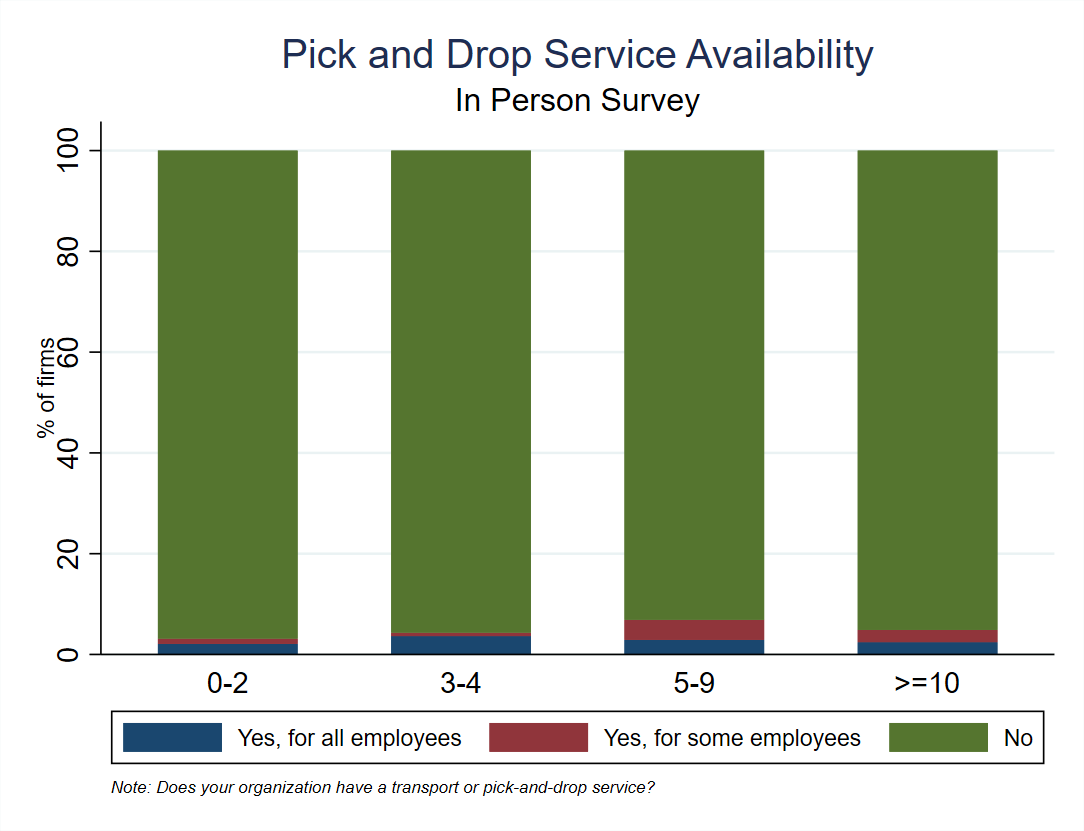

Interestingly, firms of various sizes consider where job applicants live in the city and the mode of transport they will use to commute to work when evaluating the applicants (Figure 10). Despite the indication that transport mode used for work is an important consideration in hiring decisions, only 4% of the employers surveyed provided any kind of transport to their employees (Figure 11).

Figure 10: Do employers consider applicant residence and mode of transportation, by job education level

c)

Figure 11: Availability of transport service provided by employers

Women’s labor force participation is limited by many factors. But some may be more responsive to policy changes that could expand women’s choices. The high frequency and high quality job seeker and employer data we collect on our job platform enables us to perform various experiments to investigate these constraints further and test out interventions that can help reduce them, so that women who choose to work have the opportunity to do so.

Information frictions

The fact that people want to work but cannot find suitable positions and firms want to hire but cannot find suitable candidates suggests information frictions – jobseekers do not know where the jobs are, and what skills they need for them, while firms cannot distinguish skilled and committed jobseekers from the competition. Skills mismatch may be part of a larger reason firms rely on networks to hire; they are unable to find a qualified pool of applicants without using references to screen them. Apart from providing a free job matching service by sharing CVs of suitable job seekers with employers, we have studied information frictions by providing jobseekers better information about the skills firms demand so that they can invest in them, while also providing better information to firms about jobseekers’ qualifications. Results of this experiment can help policy-makers better understand the nature of these information asymmetries and how best to tackle them through information campaigns, education interventions, technical training initiatives or employment facilitation.

Physical mobility

While there are many barriers to women entering the labor force, the provision of safe and reliable transport is one of the more policy responsive impediments. To assess the importance of safe and reliable transport in women’s decision to enter the labor force, we offer randomly allocated groups of subscribers a transport service to and from work. Some women are offered women-only transport and some mixed-gender transport; men are offered mixed gender transport. We also experimentally vary the percentage subsidy subscribers receive on their transport offer. The aim is to determine whether transport offers impact application rates and, by extension, whether transport is a major consideration in the decision to work. The different types of transport we offer, as well as the rate of discount on the transport offered, can inform policy decisions about what modes of public transportation are most effective and at what prices.