Ali Cheema and Zulfiqar Hameed

Public ratings of the police have consistently been below the ratings of other institutions in Pakistan. Only 33% of Pakistani respondents in Pew’s 2014 Global Attitudes Survey agreed that the police are exerting a good influence on the way things are going in Pakistan. This was much lower than the rating given to courts (47% agreed), the Federal Government (60% agreed) and the Pakistan Army (80% agreed). Pew’s 2009 survey found similar differences as did the Gallup survey of 2017.

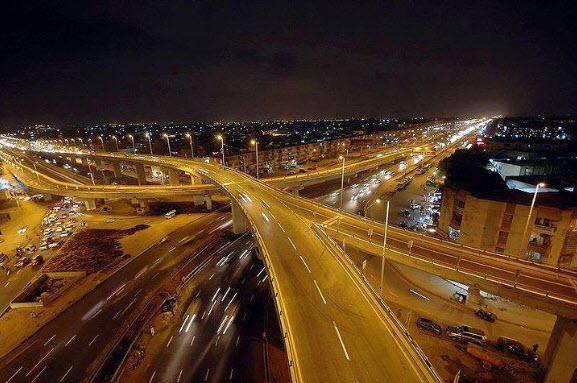

It should, therefore, come as no surprise that less than 25% of respondents in the Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives’ (IDEAS) Lahore Crime Survey (LCS) 2016 agreed that “the Lahore police are trustworthy.” Figure 1 shows that citizen trust in the Lahore police is low by global standards. The level of citizen trust in Lahore police is half the level found in London and urban centers in the U.S.

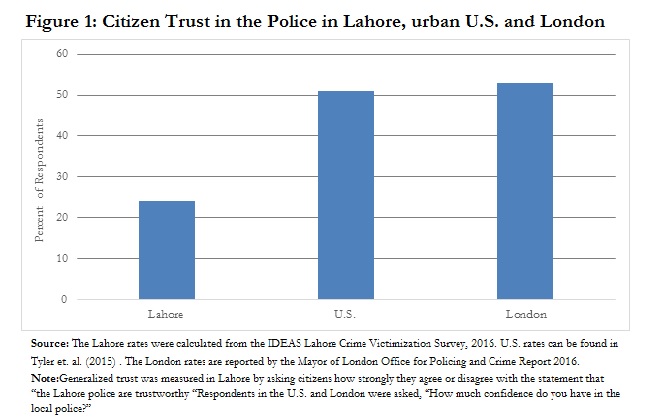

What is surprising is that that the Lahore police does much worse on citizen trust than the police services in London and the Urban U.S. despite the lower rate of victimization experienced by citizens in Lahore. The victimization rate in Lahore was 25% less than the rate in London and the Urban U.S. in 2016 (Figure 2). Low citizen trust in the Lahore police is even more surprising when one recognizes that more than 70% of the respondents in the IDEAS LCS 2016 reported that public safety had improved in their neighborhood compared to the last year. The co-existence of low citizen trust in the police with low victimization and a recognition that public safety has improved is a puzzling paradox!

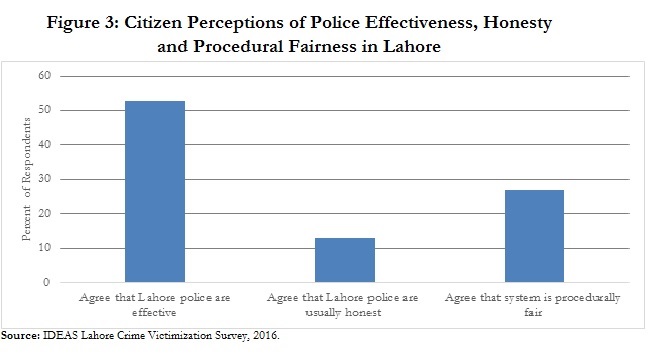

What explains this paradox? We can begin to arrive at a solution by unpacking the reasons for low trust. The IDEAS LCS 2016 asked citizens questions about three important metrics: trust in police effectiveness, trust in police honesty and trust in police’s procedural fairness. We find that while half our respondents agreed that the Lahore police are effective, around 25% agreed that they are procedurally fair and only 10% agreed that they are usually honest (Figure 3). Interestingly, while citizen perceptions of police effectiveness are in line with global averages, citizen perceptions of police honesty and procedural fairness fall well below them. The verdict of citizens is that their issue with the police is not competence; it is poor processes of service delivery.  Which parts of the policing process are adversely impacting citizen trust? We find that the First Information Report (FIR) registration system is a particularly pernicious cause of low citizen trust. Our evidence shows that the percentage of victimization incidents (reported in crime surveys) registered as criminal cases (reported in the police’s case registration data) – what we call the registration rate – was far lower in Lahore than in London and the Urban U.S. in 2016.

Which parts of the policing process are adversely impacting citizen trust? We find that the First Information Report (FIR) registration system is a particularly pernicious cause of low citizen trust. Our evidence shows that the percentage of victimization incidents (reported in crime surveys) registered as criminal cases (reported in the police’s case registration data) – what we call the registration rate – was far lower in Lahore than in London and the Urban U.S. in 2016.

We found that the Lahore police registered only 7% of victimization incidents reported by citizens in the IDEAS LCS 2016 as FIRs. The registration rate in Lahore is much lower than the crime registration rate found in Urban U.S. (19%) and in London (42%). The IDEAS LCS 2016 asked victims who reported an incident but whose complaint was not registered by the police to provide up to three reasons for the police’s failure to register. 50% said that the registration process was complex and ad hoc, while another 40% said that the current system provides poor incentives to register crime. In short, the citizens’ view is that fixing the registration process requires reforming institutional incentives at the level of the thana (police station).

The IDEAS LCS 2016 also asked respondents to report the number of times the police demanded unofficial payments from them during the past year. 50% of complainants (victims whose complaint was recorded by the police) in the survey reported direct experience of corruption. What is worrying is that direct experience of complainants with police corruption is double the level experienced by non-complainants (20%). This difference is due to the high burden of unofficial payments associated with the FIR registration that is faced by complainants. Nearly 40% of complainants report registration as the reason for the unofficial payment, which is far less than the proportion of non-complainants (5%) who report it as a reason.

The main message from this evidence is that rebuilding citizen trust in the Lahore police will not be possible without reforming the FIR registration process. In our view, there is a strong case for institutionalizing an automatic registration system that registers cases on the basis of a complaint. We recommend institutionalizing this system in cases of crime against property (theft, robbery, burglary, dacoity, extortion and attempts at these crimes) where no one is nominated as a culprit at the time of the complaint. According to our data these types of cases constitute a majority of victimization incidents in Lahore and hence the reform can have a big impact, as it will be applicable to a large number of cases.

This simple reform can go a long way in restoring citizen trust and healing the broken relationship between citizens and the police. The question is whether there is political appetite for this simple reform?

Ali Cheema is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives.

Zulfiqar Hameed is associated with the Police Service of Pakistan.

The reports on which this blog is based can be found at: