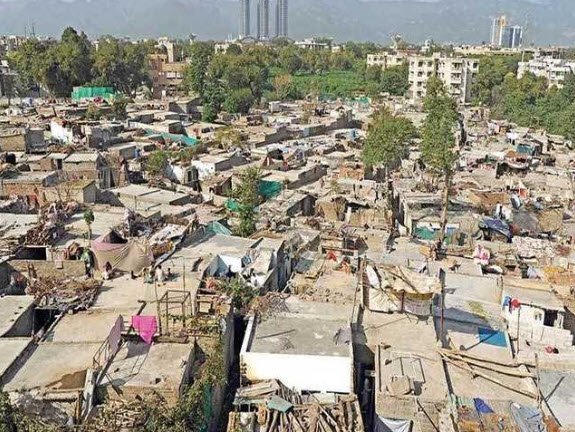

(Credit: JimC, CC BY-NC 2.0)

By Ijaz Nabi and Hina Shaikh

What is the government currently doing about Pakistan’s staggering urban challenges? Where is more work needed? Here is an overview per issue:

Housing

Pakistan faces a growing housing shortfall of approximately 4.4 million units. When provided, the quality is often substandard and low income groups receive little benefit. To redress chronic housing problems, Pakistan’s only housing policy was announced in 2002. The government’s attempt in 2005 to update the housing plan with a comprehensive policy framework remains unexecuted. Until a new, official policy is adopted and implemented, the provision of low-cost urban housing will be an elusive goal.

Local governments have a limited role in resolving the urban housing crisis. They have little control over urban land[1], a lack resources to fund schemes and are unable to borrow independently from international donors.

Many announcements of government-sponsored housing projects have made headlines (such as Ashiana[2] and Apna Ghar[3]) but remain uncompleted. The Housing and Works Ministry openly admits its failure to complete various projects. Most face bureaucratic and or administrative delays or are mired by corruption scandals and lack of political will. Where construction has taken place, low income groups have received little attention.[4] To complete one housing project, Punjab is now seeking assistance from TOKI – the Turkish Housing Development Administration. Punjab also plans to sell public land to fund low-cost housing. Several schemes are underway in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Sindh as well but progress is slow.

The House Building Finance Company (HBFC) decided in October to extend housing finance to low and middle-income groups by introducing a new priority lending scheme. The State Bank of Pakistan has issued guidelines for housing finance. Donors like the World Bank are also stepping in to help launch innovative housing products targeting under-served communities. While partial attempts like these have been made to address housing problems,, chronic housing shortages and poor quality remain unaddressed.

Water and Sanitation

In most Pakistani cities, water supply is limited and unsafe for drinking while access to waste management services remains poor.

A National Drinking Water Policy was announced in 2009 that promises safe and sustainable drinking water to all by 2025, and a Sanitation Policy was declared in 2006 aligning goals with the relevant Millennium Development Goal targets. Provincial commitment to ensuring water and sanitation services are formalized is seen in WASH[5] sector plans in Punjab and Baluchistan[6], sectoral roadmaps in Punjab[7] and other policy initiatives[8].

Initiatives have also been announced to improve waste disposal in urban centers. Karachi and Lahore, the two largest cities of Pakistan, have privatized garbage collection[9] with varying degrees of control at the local level[10]. Punjab plans to establish solid waste management companies across seven cities as part of its sanitation roadmap and commence a district-level survey to earmark sites for waste disposal.

Provinces are also improving access to clean water. The Saaf Paani company is restoring non-functional water schemes in 37 rural tehsils of South Punjab and is keen to scale-up the program across all districts (rural and urban). Water quality testing is also routinely conducted in most cities by the Pakistan Council of Research on Water Resources (PCRWR). Its most recent report estimates that 10 to 15 percent of bottled water is contaminated with excessive levels of either arsenic or sodium.[11] Most filtration plants in cities are only capable of cleaning arsenic.

Untreated industrial and municipal waste water remains a major health hazard in cities.[12] In smaller cities, sewage treatment facilities are virtually non-existent. The situation is not much different in larger urban centers.[13]

Health

As use of basic public health services remains low in both rural and urban areas, key health indicators among Pakistan’s urban poor are only marginally better than the rural poor.

After a hiatus of several years following the 18th amendment, Pakistan finally has a National Health Vision (NHV) 2016-2025 to help prioritize health interventions post-devolution. All four provinces have a Health Sector Strategy. Healthcare commissions are functional in each province, regulating public and private health facilities while ensuring their compliance to minimum standards.

Technology and improved data collection at both the federal and provincial levels are significantly changing health service delivery. Islamabad has a Health Policy Strengthening and Information Analysis Unit[14] to collect health data while health information systems are functional across all provinces. The use of internet communications technology, particularly supported by the Punjab Information Technology Board (PITB), is helping improve healthcare in the province especially for controlling dengue[15] and enhancing immunization[16]. Polio cases are declining steadily as both KP Punjab have launched successful inactivated polio vaccination (IPV) campaigns.

Health insurance is big on the cards as the Prime Minister launched the first ever national health insurance scheme in Pakistan last year while KP has introduced its own program via the Sehat Insaf Card[17].

Efforts to improve tertiary healthcare, however, remain inadequate as several large-scale projects remain incomplete.[18] Provinces are now engaging with the private sector to establish modern hospitals just as several primary health care services are also being outsourced.

Transport

Pakistan’s mega urban centers like Karachi are without a mass public transport system and investments in roads in place of public transport have led to an unregulated rise in private vehicles with fewer options of public transport for the poor.[19]

The federal government has only recently signed a two-year project to formulate the first National Transport Policy with support from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID) and the Asian Development Bank (ADB) for a safe, efficient and sustainable transport system. Provincial governments are making significant investments in low-cost public transport. These include mass transit projects in Islamabad, Lahore, Multan, Karachi and Peshawar.[20] Specialized transport bodies such as the Lahore Transport Company, Karachi Urban Transport Corporation and Punjab Metrobus Authority are helping manage city travel. But given the transportation needs of megacities, further investment in feeder or connecting routes is required. Currently, the construction of feeder-route networks to connect to Islamabad and Lahore are in the pipeline but facing administrative delays.

Inadequate public transport has fueled a rise in private taxi services (Albayrak, Uber and Careem). New provincial regulations in Sindh and Punjab will require these services to acquire route permits, fitness certificates and be subject to taxes. Vehicle inspection regime remains weak. Punjab has taken the lead by setting up vehicle inspection and certification system centers across the province.

Pakistan’s transport sector needs to prepare for the rise in economic activity expected in urban centers following investments under CPEC. Introducing the right land-use policies and investing in low-cost public transport can help meet the likely increase in demand.

Education

Although urban areas have better enrolment and learning outcomes, a significant number of children remain out of school.[21] The preference for private schools remains high, reflecting in part the low quality of public schooling.

The National Education Policy was announced in 2009 and provides broad goals. Provinces, responsible for education after the 18th amendment, have failed to reach a consensus on a revised policy. There are four education plans, one for each province.[22] Punjab’s expires this year and Sindh’s next year. The status of Article 25-A of the constitution that ensures the right to free and compulsory education post-18th amendment is still pending in KP, Gilgit-Baltistan and Azad-Jammu and Kashmir (AJK).

Provincial education departments are embedding education reforms within broader provincial plans. Punjab has adopted the roadmap approach for improving public schools. [23] The Schools Reforms Roadmap is based on “stock-takes” that track progress on education outcomes. Sindh and KP are implementing a similar model. The approach however varies across provinces in terms of leadership and management style. For example, progress in Punjab, unlike KP, is managed personally by the Chief Minister. This raises the question of whether centralized control is the right way to achieve outcomes as opposed to granting more responsibility at the local level.

All four provinces are now relying on technology-driven, “smart” monitoring techniques to manage the performance of public schools.[24] Provinces are also moving towards the merit-based hiring of teachers, now being recruited through rigorous testing conducted by a third-party service.

While the overall impact of these reforms is yet to be seen in terms of increased enrollment and learning outcomes, education roadmaps are helping to create a culture of evidence-based policymaking.

Land Management

Unregulated land use remains one of the top causes of ill-planned urbanization.

A policy mandate to manage urbanization has been slow to emerge at the federal and provincial levels. The need for smarter urban development first appeared at the heart of Planning Commission’s New Framework for Economic Growth in 2012. The incumbent government’s “Vision 2025” and 11th Five Year Plan (2013-18) roll out a similar agenda. Vision 2025 particularly emphasizes legal reforms for zoning, commercialization, taxation and improving urban infrastructure.

The Planning Commission recently established the Urban Planning & Policy Center to pursue smart, sustainable urban development in Pakistan. Provinces are also gearing up. The Punjab Growth Strategy endorses support for dense urban centers to attract investment and boost productivity while urban policy units in KP and Punjab are conducting research to inform urban policies. Provinces are also digitizing land records to facilitate administrative and economic decision-making and improve land allocation in urban centers.[25]

However, provinces have not designed industrial policy that looks at land usage and development of new cities[26], especially as industrial investments under CPEC are already being made[27]. While Punjab is currently identifying areas with the best potential to develop into cities and industrial estates, other provinces need to follow suit to align economically with CPEC.

What Next?

While there are many real and headline-grabbing urban initiatives (some are successful, many are not), they are not being pursued in a systematic framework for urban development. This has led to the poor prioritization of initiatives. Sensible urban development strategies are thus now essential for all provinces.

Pakistan will launch “The State of Pakistan Cities Report 2016”[28] this year to provide updated data on key urban indicators. The rollout of the population census, after a gap of 19 years, will also be very helpful. A fresh census will depict the true extent of urbanization and the size of the urban vote bank[29].

Given the size of the urban vote bank, there are political incentives to bring about sustained change. Responding to these incentives will require being guided by evidence to pursue the right development path – and learning from best local and international experience. This makes for excellent opportunities for collaboration between researchers and policy makers and will be taken up in the final blog in this series.

Ijaz Nabi is the Pakistan country director at the International Growth Centre.

Hina Shaikh is a Pakistan country economist at the International Growth Centre.

[1] Urban land in Lahore remains under the control of the Lahore Development Authority while only a third of Karachi’s land is under the city government.

[2] Aims to provide 50,000 low-cost housing units in the next 2 years. If completed the scheme will meet no more than 0.6 percent of Pakistan’s housing shortage. The government launched a similar housing scheme back in 2010 as well. Original target was to build 50,000 housing units in 21 cities of the province but in the past 5 years the government built just 370 units in only 3 cities.

[3] The Rs 500 million Apna Ghar Scheme announced in Punjab in 2013 remains limited to files. Under this scheme, the federal government was to construct 500,000 housing units in five years, under a PPP-mode, on land to be provided free of charge by the province.

[4] Pakistan Housing Authority (under the Ministry of Housing and Works) has over the past 15 years constructed only a few thousand housing units with none for low income groups. While the federal ministry is responsible for acquisition and development of sites as well as construction and maintenance of federal government buildings it bears no direct responsibility for provision of shelter to the poor.

[5] Water, Sanitation and Hygiene services

[6] Punjab WASH sector Development Plan 2014-2024, Baluchistan has also developed a 10-year WASH sector plan undergoing approval

[7] Punjab has launched a separate road map for water and solid waste management

[8] Sindh has a drinking water and sanitation policy 2016 awaiting approval while KP’s drinking water policy 2015 stands approved. Punjab has a drinking policy 2011.

[9] In Lahore, two Turkish companies were awarded a seven-year contract, by the Lahore Solid Waste Management Company valuing USD320 mn for solid waste collection, disposal and washing, back in 2012. After five years, the Sindh Solid Waste Management Board followed suit by awarding a Chinese company a USD25 mn contract for garbage collection in 2 districts of Karachi.

[10] By appointing political leaders from Lahore on the board of the waste management company, mayor of Lahore is directly engaged in supervising efforts to keep the city clean. Sindh however is centralizing the function of waste collection at the provincial level.

[11] The water quality control cell of the civic agency in Islamabad also found 53% of the water samples collected from various parts of the city unfit for human consumption.

[12] In Karachi, only two of its three waste water treatment plants are working, processing around 11% of the city’s sewage with more than 400 million gallons of waste water being dumped untreated into the rivers and, ultimately, into the ocean every day. A survey conducted by the AJK environmental protection agency has said that more than 70% spring water is being contaminated by sewerage lines running close to springs.

[13] After about seven years in operation, the only sewage treatment plant in the federal capital was closed down due to the faulty equipment and insufficient inflow of sewage. AJK government also claims to spend millions of rupees on water supply schemes but there has no visible change. Karachi has only recently launched a Sewage Treatment project, to be completed by 2018, for treating 460 mn gallons of sewage per day

[14] Established in 2015, it is equipped with a dashboard to collect credible data related to healthcare with support from USAID.

[15] A specialised Dengue Tracking System, based on an Android phone application given to field workers helps them keep records of dengue-related spraying activities by uploading geo-tagged photos of the spraying through the application.

[16] A digital system, E-Vaccs, launched in 2014 is monitoring the attendance of all vaccinators sent out into the field making immunization campaigns especially effective leading to rapid rise in coverage and increasing attendance of vaccinators from 36 to 94%.

[17] Plans to provide 1.8 million families across the province free treatment facility in public and private sector hospitals.

[18] A maternity healthcare project the Mother and Child Hospital, much needed for Rawalpindi, was started in 2005 at a cost of Rs2.5bn by the federal government remains unfinished to date. Other projects that remain incomplete include the construction of Surgical Tower at Mayo Hospital and extension of Services Hospital OPD in Lahore.

[19] Overall, inefficiencies in the performance of the transport sector costs Pakistan’s economy 4 to 6 percent of GDP – ADB estimates – Werner E. Liepach, ADB Country Director

[20]Metro Bus projects (orange and green lines) in Lahore, Multan, Islamabad-Rawalpindi and now Peshawar. Under transport infrastructure, these projects are now included within the CPEC framework such as rail based mass transit projects for all provincial capitals under which comes the Peshawar greater circular railway, Quetta circular railway, Karachi Circular Railway (KCR) and Lahore Orange Line train projects

[21] Close to 10 percent of all children in Lahore, Karachi and Peshawar remain out of school. Currently Pakistan has the highest number of out of school children in the world estimated at 12.3 million at primary level.

[22] These plans can be accessed from the provincial education department websites

[23] Sir Michael Barber’s ‘deliverology approach is based on first understanding the service delivery chain from top to bottom and then establishing a small team in a central delivery unit, gathering performance data to set targets and then tracking them periodically

[24] KP has launched the first ever automated management system for schools. Punjab has launched a smart monitoring of school initiative, employing over 900 monitoring and evaluation assistants to make field visits and collect data on android tablets. Sindh’s clustering policy 2016 aims to centralize control of government schools by grouping schools within close proximity to ease coordination and monitoring and developed a directorate of monitoring and evaluation. Balochistan is using its BEMIS cell to engage in software-based monitoring activities.

[25] The Sindh Revenue Board has computerized close to 95 percent of the province’s rural and urban land, while Punjab plans to do the same for urban land following complete digitization of all rural land records. KP, AJK and Balochistan are also computerizing their land records though progress has been slower.

[26] Punjab is looking at the potential to develop a new city to act as an industrial zone[26] along the Lahore-Islamabad motorway

[27] The Planning Commission confirms nine industrial parks, to act as primary hubs of industrial activity in the country, are included in the CPEC framework to be built across four provinces

[28] Report is being spearheaded by the Ministry of Climate Change (MOCC) with technical assistance from the United Nations Human Settlements Program (UN-Habitat) and funded by the Australian Government. This will provide updated information on key urban indicators for first level cities across Pakistan, establish appropriate urban baselines, analyze development trends and challenges to estimate the potential for investment and growth.

[29] Current estimates suggest that about 40% of the total electorate is now urban

Hina Shaikh and Ijaz Nabi

Hina Shaikh and Ijaz Nabi