Menu

Electricity reforms when electricity is an entitlement: The case of Lahore, Pakistan

Contrasting electricity outage patterns in low- and high-income neighbourhoods in Lahore and Karachi suggest that political control over electricity distribution utilities makes privatisation and market-oriented reforms challenging.

Countries strive to provide affordable, reliable, and efficient supply of electricity to their citizens. Reforms are integral to reaching better standards of public utilities provision. The countries with the highest standards of electricity delivery are the ones who have successfully implemented market-oriented reforms in their energy sector.

The demand for reforms in the energy sector can come from within the country (middle-income consumers asking for better service delivery; commercial and business elite seeking patronage) or from the outside (international lenders pushing for privatisation). Despite such insistence, reforms can be difficult to administer. The concept of public goods, in this case electricity, as a right/entitlement offers insight into why reforms might be opposed by citizens as well as politicians.

Electricity provision in Lahore: politicians as a service assurance channel

Lahore, Pakistan’s second largest city, provides an important test case for whether citizens continue to make claims to the state for utility provision and if this model of state-owned service delivery restricts electricity reforms. Lahore is relatively ethnically and religiously homogenous; it is also electorally competitive and receives considerable attention from political parties hoping to control the centre.

In Lahore, people approach politicians for service-related issues, such as electricity outages or delayed repair/maintenance work. Politicians with contacts in the bureaucracy at Lahore Electricity Supply Corporation (LESCO) – a distribution company that purchases electricity from the national grid – get the issues resolved. Members of National Assembly and Provincial Assembly often hold kutcheris or open forums at their place of residence for precisely this reason – to appear approachable and open to solving voters’ needs.

The ability of politicians to redistribute public goods, by virtue of either their formal power while in office or informal and extra-legal networks, is considered an important dimension of their electoral success. Additionally, they claim credit for electricity supply at subsidised rates.

In Lahore, mid-level bureaucracies have expanded in the last decade, and control over postings has become an important source of power and leverage for parties. Political parties stand to gain electoral benefits by increasing employment for special interest groups, particularly where margins for victory are narrow.

Although, in this system of patronage, there are instances of non-partisan gains where parties stand to benefit by simply ‘being useful’ to the general public, the overall inefficiencies and problems related to public service delivery endemic in the power sector are never addressed. In fact, reforms meant for improvement are resisted.

Electricity as a ‘right’: contrasting policies in Lahore and Karachi

LESCO currently faces challenges with recovering bills from government offices; it also incurs up to 6% in commercial losses from non-payments and theft (LESCO Operational Audit Report, 2011) and has faced the threat of privatisation for decades. It is under considerable pressure to improve bill payments from the national regulator and international lenders. Despite this, the province’s dominant political parties have resisted. Given the patronage and influence of politicians in LESCO, it is not in the interest of either of the two big political parties to privatise the electricity distributor of the region.

Lahore is still sheltered from the worst of electricity outages when compared to other cities of Punjab and Pakistan. Electricity distribution in all areas across Lahore is uniform, despite the 2013 National Power Policy’s recommendation that “load-shedding” [footnote]Load shedding is synonymous with an electricity outage. During load shedding, power distribution companies deliberately reduce electricity consumption by switching off the power supply to a group of customers.[/footnote](should) be focused on areas of high theft and low collections”. This contrasts with the practices of the private distributor (K-Electric) in Karachi, which engages in higher loadshedding in the areas with lower revenue recovery.

Lahore’s indiscriminate power supply, despite revenue losses in the form of theft and non-technical losses, suggests that electricity is perceived as a ‘right’ or ‘an entitlement’. It is to be provided to everyone, regardless of bill recovery and/or paying capacity of the consumers, and not as a commodity (which is how it is treated in Karachi).

K-Electric in Karachi is more likely to aggressively pursue pay-for-use policies, where low-income communities that have more defaulters are likely to get targeted with higher outages.

-

- As discovered by previous studies, very low-income neighborhoods (which are high revenue-loss neighborhoods) in Karachi experience over eight hours of outage in the summer. In Lahore, this figure is closer to five hours.

-

- On the other hand, an upcoming report by Erum and Javed finds that while higher income (low revenue-loss) neighborhoods in Karachi experience 0-2 hours of outage, even in peak summer months, high income residents in Lahore regularly report 4.5 hours of outage.

-

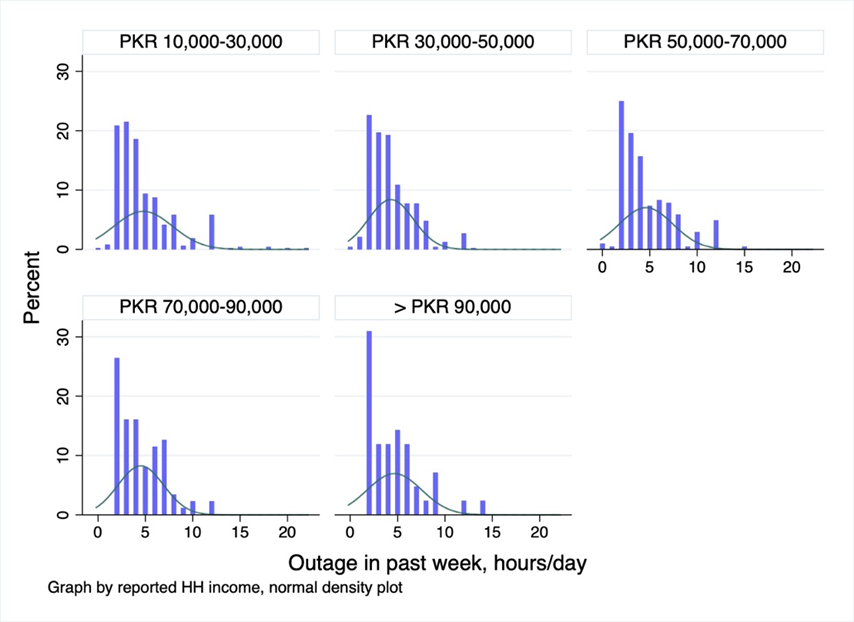

- Preliminary results of the same study suggest that at least as far as outages are concerned, LESCO does not prioritise high-income neighborhoods over low-income ones, and that outages are evenly distributed.

Figure 1: Reported electricity outages for Lahore in past week by income category, September-October 2022.

Note: Irrespective of income level, most households report 1-5 hours of outages in Lahore. Lower-income households (which tend to be in high revenue-loss areas) do not report more hours of electricity outage than more high-income ones.)

Perceptions and patronage as challenges for energy sector reforms

The construction of electricity as entitlement poses problems for reforms in the energy sector. Residents of Lahore enjoy a relatively high degree of service provision, backed by political patronage; in turn, politicians capitalise on the status quo to garner support from their electorate. Resistance to electricity reforms will come, naturally, from both stakeholders. The present subsidies for consumers in the energy sector will be another point of contention when energy sector is reformed. The roll back of subsidies and the subsequent increase in prices are likely to fuel public discontent.

An understanding of perceptions – whether a given public good or service is perceived as a right or as a commodity — is critical to energy reforms in Pakistan. However, these understandings should be coupled with commitments to environmental justice and equitable access. For example, the dual findings of relatively good provision to low-income groups, and a highly mobilised sense of entitlement in Lahore, might pave the way for more diverse forms of energy provisions – decentralised grids and investments in renewable energy to support the demands of the citizens.

Efforts should be made to close the national gap in access to energy across cities, and to continue to shield the most vulnerable citizens from inevitable climate and environmental shocks, that could lead to social unrest and negative impacts on income and livelihoods.

Numair Liaqat is a Country Economist for the International Growth Centre (IGC) in Pakistan.

This blog originally appeared on the International Growth Centre’s (IGC) website here.