Menu

Empowering Women, Nourishing Futures: Breaking the Cycle of Child Malnutrition in Pakistan.

Introduction

Child malnutrition is a significant public health concern in Pakistan, particularly in low-income areas of Punjab. This blog explores the relationship between female empowerment and child malnutrition rates. It looks at the concept of female empowerment from a mobility lens in Pakistani culture; its limitations, and the subsequent impact on access to essential resources for women and children. It also analyzes how limited access to such basic resources leads to a high prevalence of child malnutrition in Pakistan. Finally, this blog explores how efforts to empower women and enhance their mobility can contribute to a decrease in child malnutrition rates.

Restricted Mobility; A barrier to Empowerment

According to the European Institute of Gender Equality, women’s empowerment encompasses self-worth, autonomy, equal access, personal agency, and the power to shape society. In Pakistani culture, women generally do not enjoy the same freedoms and position in society as their male counterparts do; this trend is more salient in low-income areas. The Global Gender Gap Report 2024, which is a comprehensive gender equality assessment conducted by the World Economic Forum, ranked Pakistan 146th out of 147 countries on gender parity. This highlights the significant gender disparities in Pakistan. With regards to gender disparities, labor force participation is a good indicator of female inclusion thus portraying empowerment. “The overall labor force participation rate (LFPR) of women in Pakistan at 21% stands well below the global percentage at 39%. At the national level, the refined LFPR of women (aged 15-64 years) is very low at 26% compared to 84% for men” (unwomen.org).

The Punjab Commission on the Status of Women defines female mobility as a woman’s unrestricted freedom to move within and beyond her home, community, or country without facing threats or obstacles. This includes the ability to access transportation, move freely in public spaces, and travel for work or education. Women’s freedom of movement is intrinsically linked to their overall empowerment in Pakistan. While progress has been made, deeply rooted cultural norms, safety concerns, and inadequate transportation systems continue to restrict women’s ability to fully participate in society, limiting their access to education, employment, and healthcare.

Consequently, women may be unable to seek timely medical attention for themselves or their children, leading to poorer health outcomes, including higher rates of child malnutrition. Moreover, limited mobility can isolate women from support networks and hinder their ability to participate in community decision-making processes. Participation in key matters is vital as women are primary caregivers with a deep understanding of children’s needs. Their involvement in healthcare improves decision-making, promotes health education, and ensures better child outcomes.

This lack of agency can further perpetuate cycles of poverty and malnutrition. Addressing the issue of female mobility is crucial for improving the overall health and well-being of women and children in Pakistan. Efforts to empower women and promote gender equality must include strategies to enhance their mobility and access to essential services.

Malnourishment Crisis in Pakistan

Child malnutrition is a severe health condition affecting children who don’t receive adequate nutrients from their diet. This can manifest as undernutrition, where children consume insufficient food or essential nutrients, leading to stunted growth, wasting, or being underweight. Conversely, overnutrition occurs when children consume excessive calories and unhealthy fats, resulting in obesity. Both forms of malnutrition have detrimental long-term consequences for children’s physical and mental development. According to UNICEF stunting is a complex issue stemming from both insufficient and inadequate nutrition, among frequent infections and poor sanitation.

Pakistan, as a developing country, faces a severe malnutrition crisis, with alarming rates of stunting and wasting among children.” Nearly 10 million Pakistani children suffer from stunting” (unicef.org)

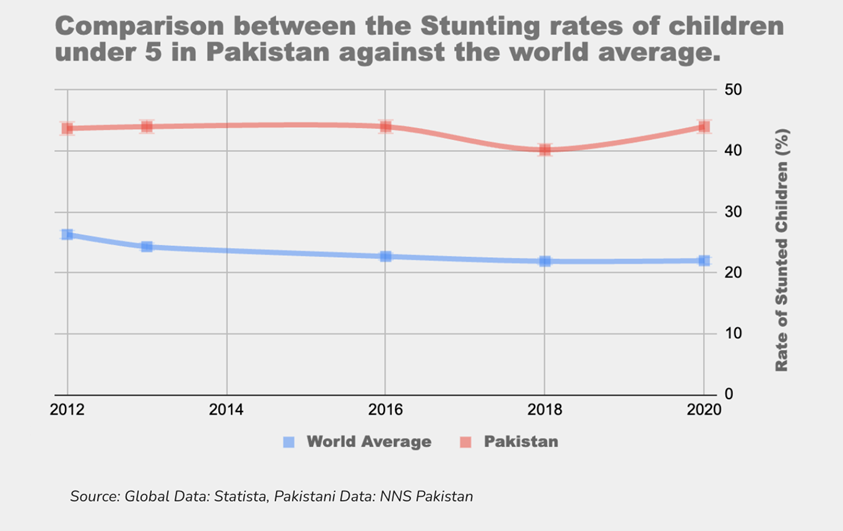

The graph below starkly contrasts the global and Pakistani rates of child stunting rates among children under five, with Pakistan exhibiting a significantly higher prevalence, underscoring a critical issue for children’s welfare in the country.

For the last decade, stunting rates in children under age 5 have been far greater than the worldwide average as can be seen in the graph. This is not due to any one single factor, rather it is, in most cases, a cumulation of multiple aspects. One of these major factors is the lack of access to clean drinking water. Albeit, there isn’t a direct link between malnourishment and drinking water, it plays an important role as a vector for various water-borne diseases “Contaminated water and poor sanitation are linked to transmission of diseases such as cholera, diarrhea, dysentery, hepatitis A, typhoid and polio” (World Health Organization).

Drinking contaminated water impairs the body’s ability to retain nutrients essential for growth; rather than being absorbed, they are excreted out of the body either through vomiting or diarrhea. This is a serious problem in Pakistan, as “53,000 Pakistani children under age 5 die annually from diarrhea due to poor water and sanitation” (unicef.org). Additionally, the United Nations Children’s Fund estimates that around 70% of the households in Pakistan drink bacterially contaminated water which means children living in these households have a higher susceptibility to water-borne diseases and are consequently at a higher risk for malnourishment.

Empowerment: A Better Path to Nutrition

Female empowerment is essential for effectively managing Pakistan’s complex malnutrition problem, especially when it comes to the vital element of accessing safe drinking water. Empowering women with increased mobility and the agency to fight for increased access to clean water sources is crucial for minimizing the incidence of water-borne illnesses in their children. Moreover, women with higher levels of education are more likely to recognize the significance of cleanliness, hygiene, and clean water for general health. Hence, increasing female mobility in terms of their access to education at a young age has far-reaching positive impacts on the female herself as well as her future family. In short “improvement in women’s empowerment s are expected to lead to the well-being of children in the form of reduction in their nutritional status” (ghrp.com).

The Global Health Research and Policy advocates for individuals to become financially independent, thus enabling them to make investments in water filtration systems or support neighborhood-based projects to guarantee a steady supply of safe drinking water for their families and communities. To further combat malnutrition, women’s leadership in community development is essential. It is possible to give vulnerable groups’ needs—such as those of children and expectant mothers—priority by incorporating women in decision-making processes about resource allocation and water management. Empowered women are better able to carry out nutrition programs, encourage breastfeeding, and make sure that kids have access to wholesome food and clean water. Pakistan needs to address malnutrition holistically if it is to become a healthier and more just society.

Conclusion

Albeit, the statistics paint a bleak picture, there is hope. In the struggle against child malnourishment, it is possible to utilize a potent weapon by empowering women in Pakistan. Women who have greater mobility and use it to seek employment can take advantage of their financial security by making health and nutritional investments for their children, whether it may be as simple as immunization or drinking filtered water. Women can become advocates for constructive change in their communities when they receive education about good nutrition and hygiene habits.

The way forward requires a multi-pronged approach. Investments in public transportation infrastructure and cultural awareness campaigns promoting gender equality can increase female mobility. Educational programs focused on nutrition and sanitation, coupled with initiatives to support women’s leadership in community development, will equip women with the knowledge and agency to break the cycle of malnutrition. In short, by prioritizing female empowerment, Pakistan can build a healthier future for mothers and children alike.

Tashfeen Faisal is a student at Lahore Grammar School – International. He was part of the first cohort of CDPR’s Mentorship Program.

Sources

“Empowerment of Women.” European Institute for Gender Equality, 17 July 2024, eige.europa.eu/publications-resources/thesaurus/terms/1246?language_content_entity=en. Accessed 1 Aug. 2024.

“LinkedIn.” Linkedin.com, 2024, www.linkedin.com/pulse/pakistan-faces-challenges-gender-parity-world-forum-global-jahangir-9kxyf/. Accessed 1 Aug. 2024. https://pakistan.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2023-07/summary_-nrsw-inl_final.pdf

World Bank. (2022). Pakistan Development Update: Harnessing the Demographic Dividend. [Report]. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://pcsw.punjab.gov.pk/system/files/overcoming.pdf

“4 Things You Need to Know about Water and Famine.” Unicef.org, 2022, www.unicef.org/stories/4-things-you-need-know-about-water-and-famine#:~:text=Unsafe%20water%20can%20cause%20diarrhoea,to%20waterborne%20diseases%20like%20cholera. Accessed 1 Aug. 2024.

World. “Drinking-Water.” Who.int, World Health Organization: WHO, 13 Sept. 2023, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drinking-water#:~:text=Contaminated%20water%20and%20poor%20sanitation,individuals%20to%20preventable%20health%20risks. Accessed 1 Aug. 2024.

Yaya, Sanni, et al. “What Does Women’s Empowerment Have to Do with Malnutrition in Sub-Saharan Africa? Evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys from 30 Countries.” Global Health Research and Policy, vol. 5, no. 1, BioMed Central, Jan. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-019-0129-8. Accessed 1 Aug. 2024.

“Nutrition.” Unicef.org, 2017, www.unicef.org/pakistan/nutrition-0. Accessed 2 Aug. 2024.