This blog post is based on a session of the Lahore Policy Exchange held at the Consortium for Development Policy Research on Friday, 4th October with Ahmed Rafay Alam, Dr. Fozia Parveen, and Zahid Aziz.

Cities do not need to be located near large water bodies such as rivers, lakes, or the sea to be vulnerable to flooding. Rapid development and urbanization, often unplanned in developing countries, has resulted in pluvial flooding[1] in urban areas to become increasingly common all over the world. Urbanization creates city landscapes that are unable to absorb or otherwise manage rainfall. Subsequently, pluvial floods occur when an extreme rainfall event creates a flood independent of an overflowing water body, resulting in a situation where water flows into an urban region faster than it can be moved out. Urban flooding is more localized, has the potential to be more frequent, and is not as well understood as other forms of flooding.

The reasons for urban flooding are multiple and varied, particularly in developing countries. These include lack of rainwater storage and management systems, inadequate waste disposal mechanisms, institutional capacity, urban governance, and development which ignores topography. The problem is compounded by ageing and overburdened drainage networks, climate change, and the unhindered expansion of cities.

Many cities even in the developed world are now being forced to devise solutions to control and mitigate the effects of pluvial flooding. In the United Kingdom, pluvial flooding is regarded as a greater threat than both fluvial (river) and coastal flooding combined. This is partly because of the unpredictable nature of urban floods. There are no easily defined flood plains (the land surface adjacent to a water body) for urban areas as there are for rivers and seas, and the probability of flooding ultimately depends on how buildings and sewerage react to a sudden increase in water flows. However, one guiding principle that can help tackle urban flooding is that water will always flow to the lowest point.

Most recently, life in Pakistan’s two largest cities[2], Lahore and Karachi, came to a virtual standstill as a result of flooding during the Monsoon season with significant loss of life, property, and economic activity. Lahore in particular has suffered from urban flooding for many years, and mitigation efforts have either not been made or have been sub-optimal.

Source: https://www.dawn.com/news/1494534

Source: https://www.dawn.com/news/1494534

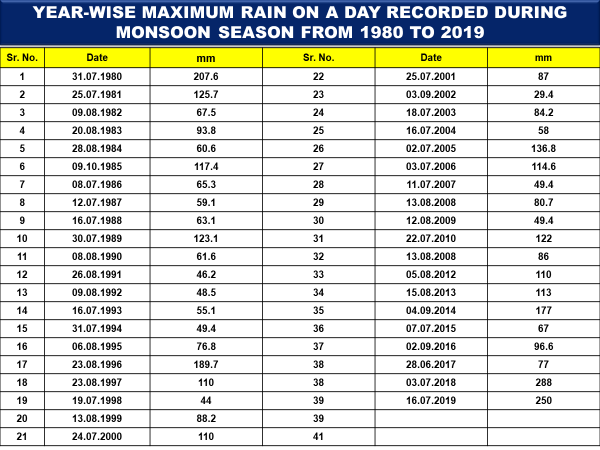

The solutions to urban flooding vary greatly by location as each city faces a unique set of challenges. Even within Pakistan, reasons for urban flooding vary across Karachi and Lahore. In July 2018, Lahore received up to 288 millimeters of rain and again this year, rainfall of up to 250 mm was recorded (in one month). This is in stark contrast to previous years when the highest amount of rainfall Lahore received was 177 millimeters in 2014 (see table below). In comparison, Karachi received rain up to 55 millimeters when it rained for five consecutive days in September. However, despite the vast difference in the amount of rainfall received, Karachi found itself much more ill-equipped for the subsequent flooding.

Source: WASA, Lahore

Before a discussion on the causes and solutions of urban flooding can begin, it is important to understand the impact of urban flooding and why it deserves our immediate attention.

The costs of urban flooding

Flooding in urban areas is capable of causing a great deal of destruction in a short period of time with the effects extending beyond flooded streets and diminished mobility. Unlike floods associated with rivers and seas, the visual impact of urban flooding is significantly lower, but the impacts on economic activity prove to be much more damaging in the long-run, even though the effects may not be immediately identifiable, and may be even more difficult to quantify. In a report published by the Center for Disaster Resilience at the University of Maryland and Center for Texas Beaches and Shores at Texas A&M University, the cost of urban flooding was identified as a series of effects on individuals and communities “such as loss of hourly wages for those unable to reach their workplaces; hours lost in traffic rerouting and traffic challenges; disruptions in local, regional, and national supply chains; or school closings with resultant impact on parents.”

These effects are particularly damaging for those living in lower-income areas and have a disproportionately larger effect on the disadvantaged. They are also amplified in lower-income localities because of poor infrastructure and other urban services such as waste management. In Lahore, in particular, many low-income localities are “illegal developments”, with a direct impact on the quality of public services available.

An accompanying feature of flooded cities is a breakdown in power supply for prolonged periods of time. This has a direct impact on citizen well-being, as well as relief efforts by the government. It is difficult to identify whether these breakdowns are caused directly by floods, or by weaknesses in the electricity transmission infrastructure. However, given the frequency with which breakdowns occur, with or without rain, all evidence points to the latter. Deaths due to electrocution further reinforce this point.

Finally, flooded cities also increase the stress on an already weak public health sector. Stagnant pools of water create the perfect breeding ground for waterborne diseases such as cholera and malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Dense urban localities with poor sanitation help spread diseases such as measles.

What causes urban flooding?

Development and Urban Sprawl

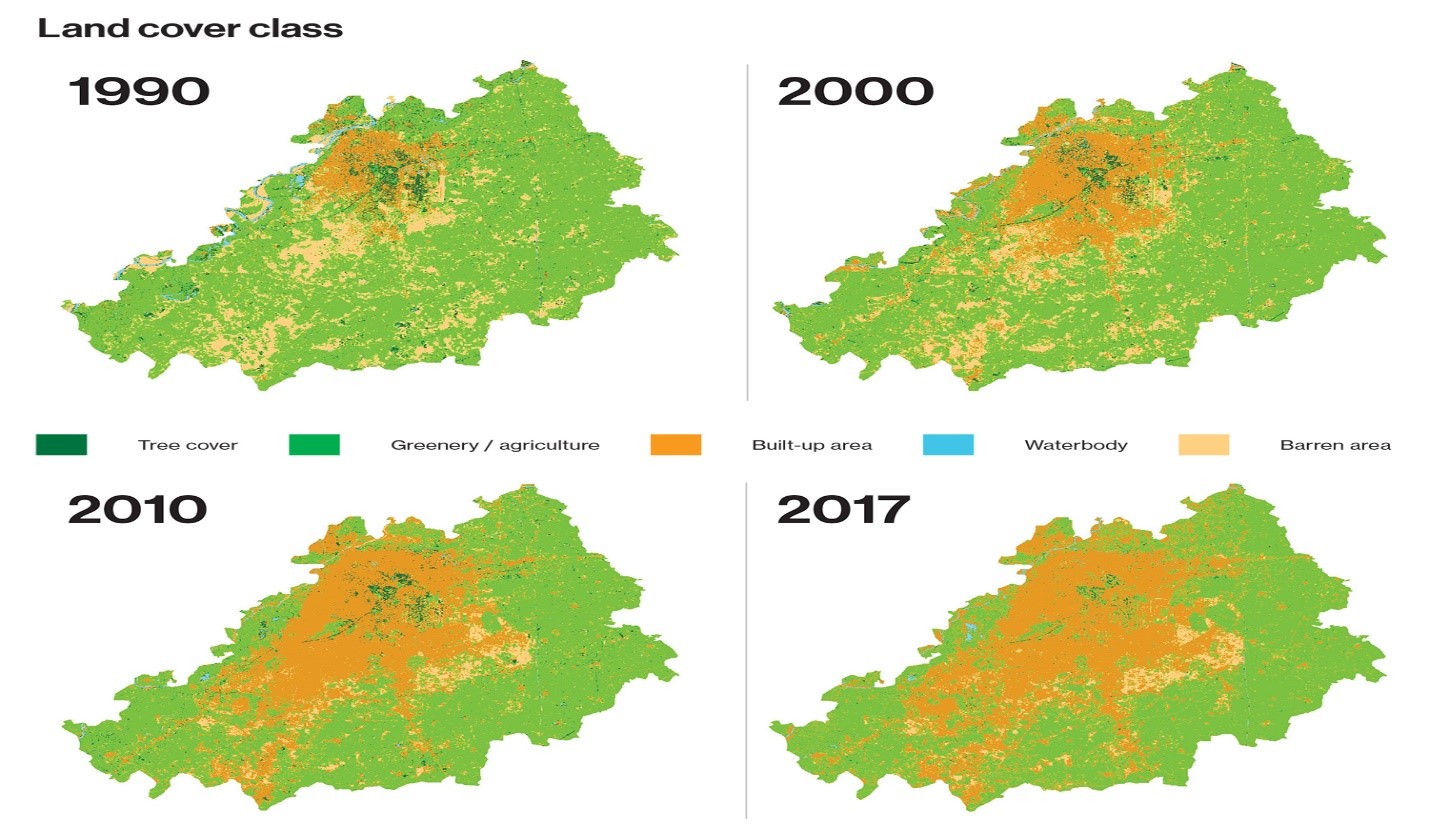

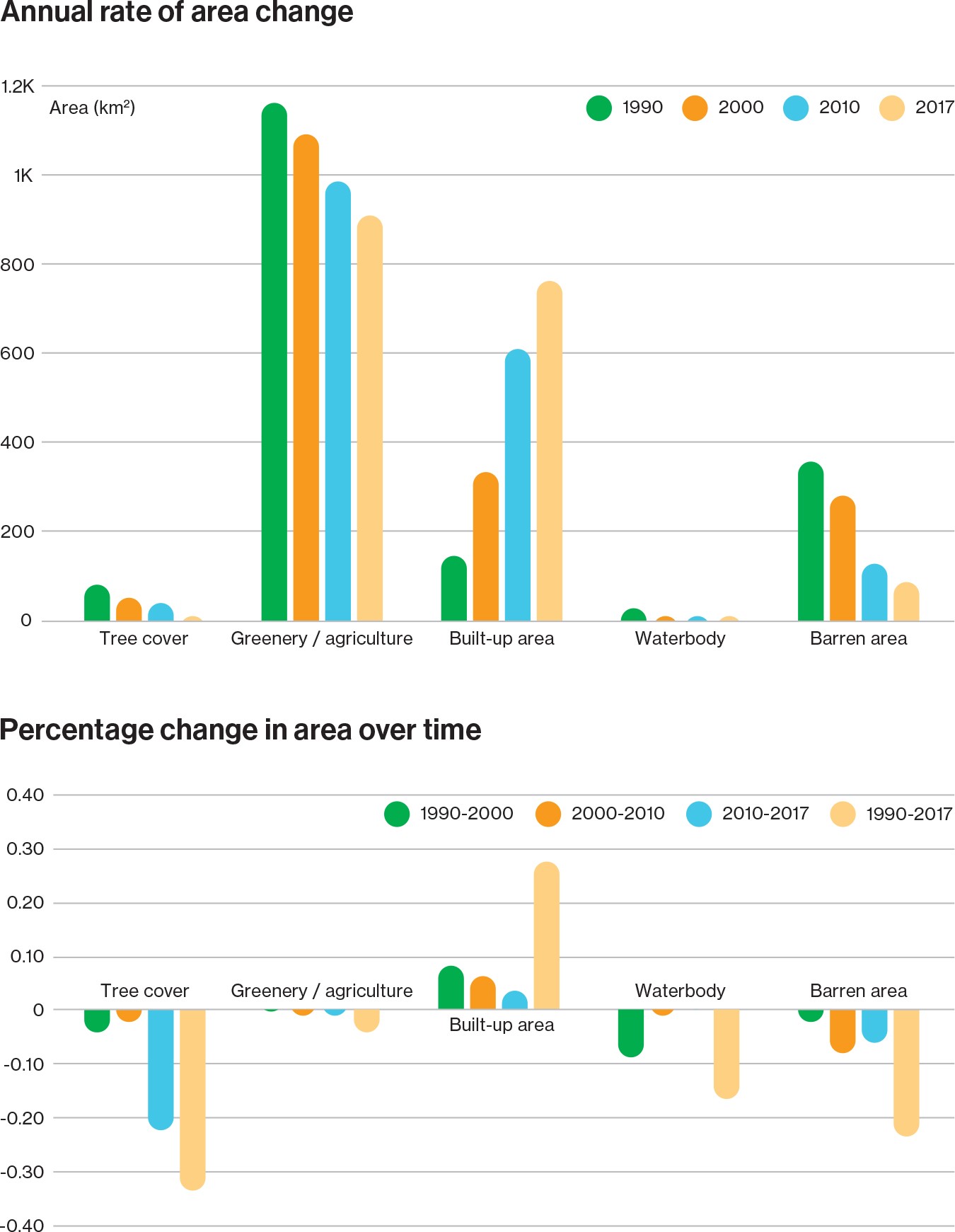

One of the largest contributing factors to urban flooding is a rapid increase in urbanization and built-up area within the city, with an associated increase in impermeable surfaces. The images below show the rate at which built-up area has increased in Lahore. Put together, between 2010 and 2017, Lahore lost more of its green cover than it did in the previous two decades.

Source: http://www.technologyreview.pk/lahore-is-losing-its-green-cover-fast/

It is not difficult to understand why these changes have taken place. Symptomatic of a poor urban planning process (and lack of depth in the profession), mega projects, such as signal-free corridors and a general expansion in the road network, were used by successive provincial governments for political mileage and to garner votes. One key failure of the process is the poor quality of Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) reports prepared, which can be defined as “the systematic examination of unintended consequences of a development project or program, with the view to reduce or mitigate negative impacts and maximize on positive ones”. Contrary to best practices, EIAs are largely considered formalities and are not used as planning tools in Pakistan.

An additional driver of the loss of green coverage is the increase in suburbia across the entire country. Gated housing societies have become the location of choice for many middle-to-high income households as a result of poor urban service delivery within city centers. These housing societies eat into the agricultural land surrounding the cities and leave little to no room for rainwater to get absorbed into the ground. Many also do not factor in stormwater drainage at the time of construction.

Source: http://www.technologyreview.pk/lahore-is-losing-its-green-cover-fast/

It cannot however be denied that Lahore’s population has grown vastly in the past two decades. In 1998, Lahore’s population stood at 5.14 million. According to the 2017 census, this number has increased to around 11.13 million. However, much of the increase in the built-up area has come about due to excessive suburban development, which caters primarily to higher-income segments.

These developments provide insights into the decision-making process of city management. Contrary to the direction most cities in the world are going in, city planning in Pakistan primarily serves the car owning elite at the expense of lower-income segments. While a signal-free corridor does make it easier to travel from one end of the city to the other, the impacts on citizen well-being, especially in lower-income segments, is ignored.

A further repercussion of an increase in built up area is the overall increase in surface temperature. According to one study published in the Pakistan Journal of Meteorology, between 2000 and 2011 the overall surface temperature of Lahore had increased by 0.73°C. This creates an urban heat island effect where monsoon winds are attracted towards high-temperature areas, potentially increasing the frequency of high-intensity rainfall events.

Weaknesses in drainage and waste disposal mechanisms

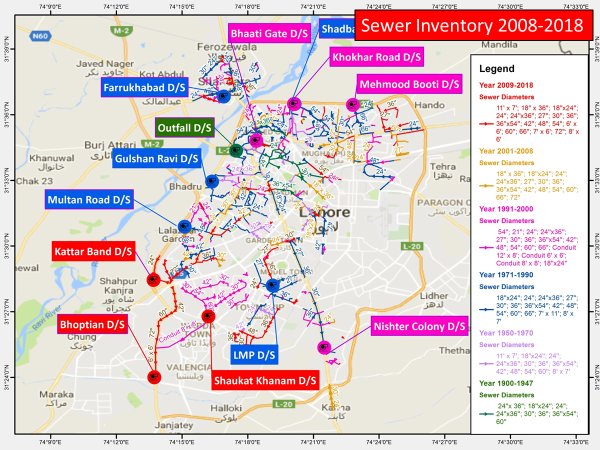

Lahore is served by eight main drains – Central, Lower Mall, Chota Ravi, Alfalah, Gulberg 1 and 2, Edward Road, Mian Mir and Gulshan-i-Ravi – and seventy-six tributary drains.

As can be seen in the image below, this network was built up in phases since Partition in 1947. The largest investment in the network came between 1971 and 1990 when 44.48 percent of the current network was built. The investments then declined over time with 31.76 percent of the network being built in 1991-2000, 14.51 percent in 2001-2008, and 3.33 percent in 2008-2018. (Source: WASA Lahore)

Source: WASA, Lahore

However, the drainage network has not kept pace with the rate of urban expansion. In many communities, the infrastructure is aging and undersized. In simpler terms, drainage networks are built with capacity limits and expiry dates. Many of the drains are nearing their expiry dates, and with an increase in commercialization and vertical building, the capacity of these drains is also being strained. This problem is compounded by an inability to maintain existing drains with resultant blockages in the entire network.

Blockages in turn are caused by three main reasons. The first is deposits of sediment in the drains due to surface water runoff. This decreases the carrying capacity of the drains leading to overflows and flooding. To address this issue, Lahore’s Water and Sanitation Agency (WASA) took assistance from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) to clear the drains of sediments in 2004. However, no permanent solution to siltation has been implemented. The second reason for blockages is the use of these drains as waste disposal sites by residents. In the absence of proper waste disposal mechanisms, the banks of open drains are often used as dumping sites. There is also a behavioral aspect of citizens at play here who choose the convenience of using open drains for dumping domestic garbage. Finally, storm water drains are also connected with domestic sewers at various points. Together, these three factors constantly depress the carrying capacity of the entire network and ensure that cities like Lahore remain prone to flooding.

Reducing the risk of urban flooding

It is not possible to make cities completely flood-proof but they can be made flood resistant. Traditionally, policymakers considered floods as something that must be responded to (hence the extensive literature on disaster management). The contention here is that cities should be designed in such a way that makes the possibility of flooding as remote as possible.

One primary difficulty that city management in Pakistan faces is that our cities have largely been built. That is to say, poor planning, or lack thereof, has already resulted in cities that are very poorly built and managed. Any reform measures now, especially infrastructure upgradation, would need to take into account the disruption caused to daily life and economic activity, as well the sheer difficulty of intervening in an urban environment that is already in place. Storm water management, indeed sewerage in general, is no exception.

Like most other reform efforts in Pakistan, making our cities flood-resistant requires a series of reform measures, both in the short-term (what is called low-hanging fruit) and in the long-term. Some of these are possible within the current governance structure, others involve an overhaul of how our cities our managed.

Going by the causes of urban flooding outlined in the previous section, the easiest reform measure, and one that could be implemented in the shortest amount of time relatively speaking, is developing proper waste disposal mechanisms in all cities, especially in low-income localities, and thereby killing two birds with one stone. Domestic waste management is a key urban service, and one that cities like Karachi struggle with even today.

The second low-hanging fruit is empowering agencies such as WASA to regularly maintain the existing drainage network. This entails mobilizing considerable resources to provide the agencies with the equipment necessary to clear the drains of sediments and domestic waste. Maintenance would also involve separating the existing domestic waste and storm water networks. This too would require considerable resources, but is an objective that is achievable within the current system.

A third short-term achievable target is to leverage intelligent urban design to control the spread of floodwater. Many cities are now using innovative concepts such as water squares to divert flood water into lower-lying areas. WASA Lahore has plans to build one such water square at Lawrence Gardens to divert floodwater from the converging point of three low-level roads. Moreover, at an individual or household level, houses are being designed to harvest rainwater to be used later on. Incorporating rainwater harvesting units in houses would considerably lessen the strain on the drainage network.

One of the more difficult challenges, and one that would require a long-term strategy is to control the expansion of cities, spread the urbanization over a larger number of cities, and ensure that the environmental impacts of cities are not ignored. Cities such as Lahore, Karachi, and Peshawar attract people from all over Pakistan, a factor which strains urban service delivery. Having multiple urban centers would make it easier to manage the cities, and drive economic growth as well. This would also entail revamping governance structure to allow decisions which impact cities to be taken at the city level. If the city is affected by floods, then the city should be responsible for developing system to tackle flooding. Consequently, the city must also then be allowed to raise the revenues required to develop those systems.

The monsoon rains and the accompanied flooding are not necessarily an evil that must be defeated. Rainfall is a central feature of our ecosystem and our urban planning and design needs to develop ways in which we can co-exist with nature in a harmonious manner.

[1] In this article, pluvial flooding and urban flooding are used interchangeably.

[2] For reasons of simplicity and data availability, this article focuses primarily on Karachi and Pakistan as examples. However, the causes and solutions will largely be the same for most Pakistani cities.

Bakhtiar Iqbal is a Research Assistant at the Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR) with an interest in urban planning.