This is part of a blog series discussing findings from the Punjab Education Sector Programme (PESP) II evaluation. In the first interim phase, survey and administrative datasets were reviewed to understand changes in Punjab’s education landscape since 2012. While the overall report discusses Punjab’s performance on various indicators, this piece looks specifically at gender trends.

Last month the World Economic Forum released the ‘Global Gender Gap Index 2018’ report ranking Pakistan as the second worst county in gender inequality. A quick review of the facts shows that female labor force participation in Punjab stands at a mere 28 percent in comparison to male labor force participation at 69 percent.[i] In terms of literacy, only 54 percent of women are able to read or write in comparison to 72 percent of men in the province.[ii] While education till Grade 10 (matric) level is compulsory across the country, girls are less likely to participate in school, regardless of age, and are more likely to drop-out when they do.

Are girls going to school?

Overall, more and more children are participating in schools, with around 90% of children ages 5 to 16 years in schools in 2016. Gender gaps in enrolment are declining as the 10 percent gap in the participation rate between boys and girls has decreased to 2 percent from 2014 to 2016. That being said, age-appropriate enrolment gaps still remain. The primary gross enrolment rate for boys was 99 percent in 2016 – still 11 percentage points higher than that of girls. [iii]

Are girls performing in schools?

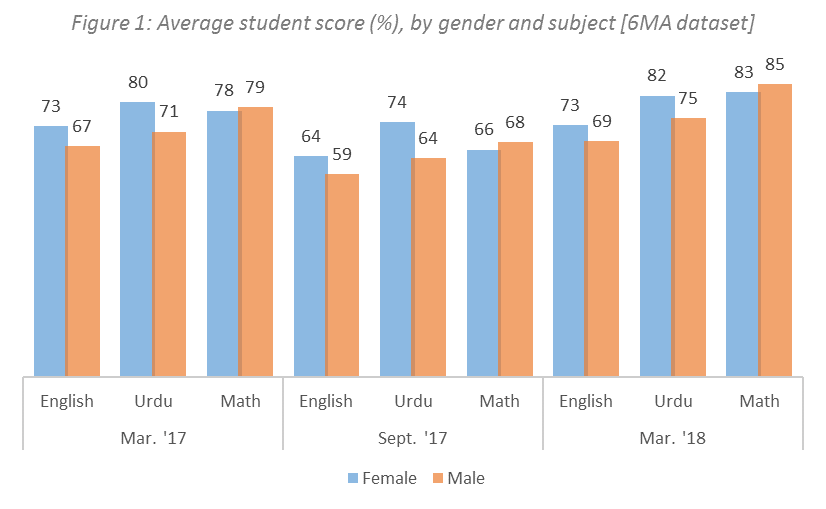

Research shows that attending any educational institution matters because children are more likely to learn in school. Moreover, if girls are in school, they tend to outperform boys in Punjab. Data from biannual assessments[iv] of grade 3 children in government and private schools shows that girls score significantly higher than boys in English and Urdu, whereas boys perform marginally better than girls in Math (Figure 1).

Female advantage in literacy persists as students progress to higher levels of schooling, as is evident from the Punjab Education Commission grade 5 and 8 examination results. A report analyzing province wide exam data that all government school students take, shows that girls achieve higher scores than boys in all subjects – Urdu, Islamiat, Ethics, English and Science – with the exception of Math. Gender differences are driven by scores in the open-ended questions, where girls outperform boys.

Despite lower participation rates and high female illiteracy, how is it that girls perform better in schools? While research attributes gender gaps in performance to a range of individual, household, and societal explanations, this cannot be investigated using the available, assessment data collected from schools in Punjab.

Are girls’ schools performing?

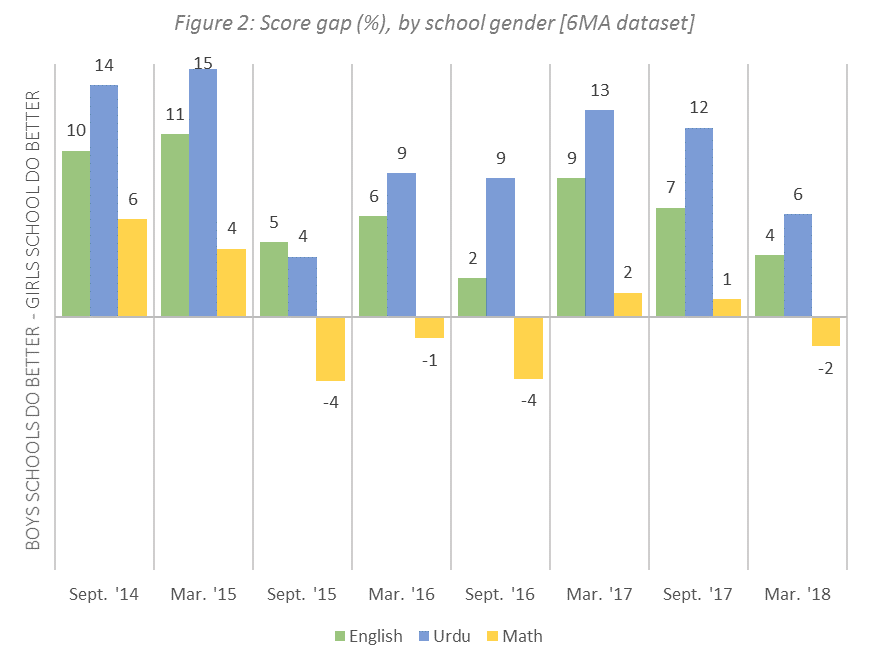

The grade 3, biannual assessment data is one avenue to explore factors affecting student learning. The dataset reports school level characteristics such as school gender, allowing us to investigate trends in score gaps by school type.[v] In Punjab a public school is either designated for girls or for boys. However, due to limited availability and access, there are often cases where boys attend girls’ schools, and vice versa, particularly at the primary level.

Analysis of mean scores on this level of disaggregation shows that students in girls’ schools consistently outperform students in boys’ schools in language subjects (differences are statistically significant). While this holds true for English and Urdu, trends in Math are inconsistent. Figure 2 shows the difference in scores between girls’ and boys’ schools, where a positive value indicates that scores are higher in girls’ schools while a negative value indicates that scores are higher in boys’ schools.

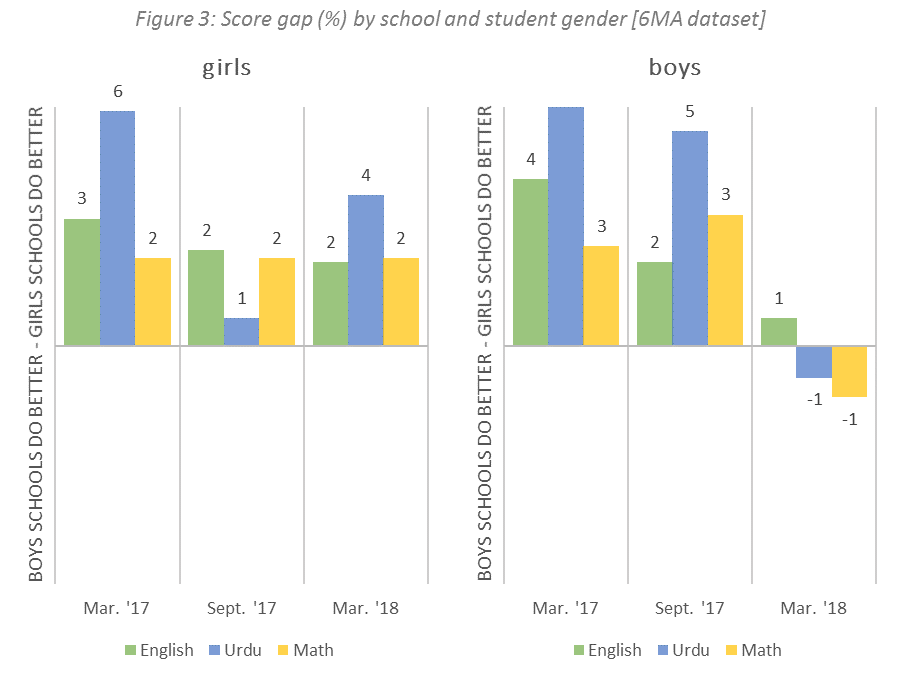

Figure 3 combines school and gender trends to show the percentage point differences in scores across school type for girls (left) and boys (right) separately. Similar to figure 2, a positive value indicates better performance in girls’ schools while a negative value indicates better performance in boys’ schools. The trends show that while girls always perform better in girls’ schools, boys also performed better in girls’ schools for two of the assessment rounds.

Our findings suggest that children perform better in public girls’ schools. But, how are they performing better? Are girls’ schools better resourced? Are the teachers in girls’ schools of a higher quality? There is a need to thoroughly understand the environment in girls’ schools (and disentangle the causality between scores of girls with that of girls’ schools) to draw lessons for the quality of education debates. Since teacher allocation depends on the type of school, in the sense that there will be no male teachers in girls’ schools, we may infer that the gender of the teacher is critical to explaining these learning differences.

Our findings suggest that children perform better in public girls’ schools. But, how are they performing better? Are girls’ schools better resourced? Are the teachers in girls’ schools of a higher quality? There is a need to thoroughly understand the environment in girls’ schools (and disentangle the causality between scores of girls with that of girls’ schools) to draw lessons for the quality of education debates. Since teacher allocation depends on the type of school, in the sense that there will be no male teachers in girls’ schools, we may infer that the gender of the teacher is critical to explaining these learning differences.

What does research tell us?

Literature on student learning outcomes finds mixed evidence on the impact of teacher gender. In Sweden, where girls are also outperforming boys in language, Holmlund and Sund (2008) observe that the performance gap is highest in subjects with predominantly female teachers among upper-secondary schools in the Stockholm area. In their analysis, however, they do not find evidence for a causal positive impact of same-sex teachers on student achievement.

In the context of South Asia, Chudgar and Sankar (2008) find that while female-headed classrooms (grades 4 and 6) perform better on language, there is a lack of statistical significance on same-gender teacher benefits, in five Indian states. They also find that the advantage of female led classrooms fades when teachers have more than 10 years of experience or have received in-service training. Aslam and Kingdon (2011) adopt a with-in pupil framework by analyzing the performance of the same student in math versus language against characteristics of a different teacher for math and language, among grade 8 students in Lahore.[vi] They find that female students benefit from the same-sex teacher, as compared to males. They also examine the role of teaching practices, finding that teachers who plan lessons, ask questions, and quiz on past lessons positively affect pupil achievement.

The role of teacher gender in performance is relevant for the policy debate in Punjab both due to the disaggregated nature of public schools and the feminisation of the education labour force. According to the Pakistan Education Statistics 2016-2017 Report, around 56 percent of government teachers and 82 percent of private teachers are women. At the primary level, this increases to 61 percent in government schools and 87 percent in private schools.[vii] While Punjab has undertaken a number of reforms to increase both education access and quality, the role of female and male teachers needs further study at the provincial level.

Despite persistent gender disparities in the country, as highlighted in the Global Gender Gap Index 2018 report, public girls’ schools (and girls) are performing better than boys’ schools in Punjab. This piece has explored one possible explanation of this – female teachers. Something seems to be going right in these schools, and we need better assessment data and research on school segregation and learning environments in girls’ schools to find what it is.

Bibliography

Aslam, M., & Kingdon, G. (2011). What can teachers do to raise pupil achievement? Economics of Education Review, 30(3), 559-574.

Chudgar, A., & Sankar, V. (2008). The relationship between teacher gender and student achievement: evidence from five Indian states. Compare, 38(5), 627-642.

Holmlund, H., & Sund, K. (2008). Is the gender gap in school performance affected by the sex of the teacher? Labour Economics, 15(1), 37-53.

Endnotes:

[i] Pakistan Labour Force Survey, 2014-15.

[ii] Ages 10 and above. Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement Survey, 2015/2016.

[iii] Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement Survey, 2013/2014 and 2015/2016.

[iv] The DFID six monthly assessment (6MA) has been conducted bi-annually (March and September) between September 2014 and March 2018 on a representative sample of government and Punjab Education Foundation schools across Punjab. In each round, students in Grade 3 are tested on basic literacy and numeracy student learning objectives spread across grade 1 and 2 level of difficulty. Student gender is only available from March 2017 onwards, which provides us with three rounds of comparison.

[v] Trends by school type also show that Punjab Education Foundation schools outperformance government schools, with the gap decreasing over time. Furthermore, no pattern has been observed by school level (ie. primary, middle, high, etc).

[vi] They assume that student ability across subjects is constant.

[vii] Teachers from the primary to the higher secondary school level.