The water crisis in Pakistan is both a supply and a demand side issue with various contributing factors at play. On achieving statehood in 1947, the country held 5,300 cubic meters of water per capita, which has now been reduced to 1000 cubic meters. Pakistan faces continued clashes with upper riparian India over rights to water from the Indus river. Moreover, a historic lack of political will to consider the repercussions of water scarcity has led to underinvestment in water infrastructure and sub-optimal pricing of water across all sectors. Underpricing and inadequate regulation has created a pervasive culture of irresponsible water consumption and lack of conservation. However, since the reasons for mismanagement stem from several quarters, the solution for optimal utilization of water is not straightforward.

Pakistan’s water scarcity is the result of a combination of factors, including the mismanagement of water resources and burgeoning population growth. Currently Pakistan’s economy is one of the world’s most water-intensive economies in terms of cubic meters consumed per unit of GDP. Further, its water productivity is among the lowest, producing 0.13kg of agricultural output per cubic meter, while that of the US’s stands at 1.3kg. Low productivity compounded by spiraling population growth has meant dwindling water quantities available per person. For these reasons, the country was declared as water scarce in 2005.

To discuss this further, the Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR) organized a policy talk around issues of water mismanagement in Pakistan. The panel hosted the Minister for Irrigation, Punjab, Mr. Mohsin Leghari, Dr. Erum Sattar, Visiting Fellow, Harvard Law School, and Mr. Arif Nadeem, CEO, Pakistan Agriculture Coalition (PAC). The session was moderated by Mr. Ali Habib, Managing Director of an environmental consulting firm, HimaVerte.

Dams may not effectively address water scarcity

Constructing dams at upper riparian locations of the Indus river basin can be considered as a means to evenly control year round water flows going all the way down to Sindh. Mr. Leghari emphasized on the need to develop a consensus on the Kalabagh Dam. He further explained that in addition to good returns on investment, the project promises, contrary to popular belief, 88% share in the additional water storage for all provinces other than Punjab, with Sindh being the major beneficiary. Yet, despite this knowledge, politicians are unable to find a way forward.

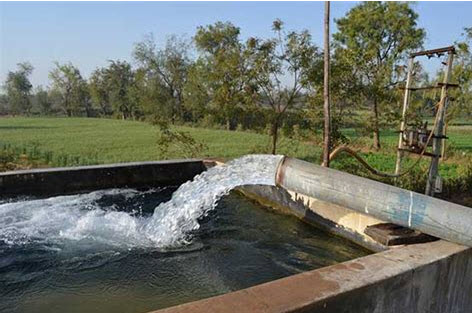

Construction of dams, however, will not address the emergency of dwindling water resources and availability of clean drinking water unless agriculture methods are modernized. More than 90 percent of fresh water is diverted towards agriculture. Agriculture in Pakistan relies on inefficient methods that over-extract and waste water. Lack of technological advancement in agriculture is perpetuated by misaligned state incentives for uptake of technology and use of more productive seeds. Farmers find it economically viable to grow water-intensive crops such as sugar cane and rice and waste water, even though these crops do not contribute significantly to the economy.

Mr. Arif Nadeem discussed it would be more financially and environmentally sustainable to import (instead of over produce) sugar, and shift to value-added crops like sesame seeds with high economic value and comparative advantage. Such crops not only utilize less water but also generate foreign exchange.

The government should thus redirect farmers towards sustainable agricultural choices through imposition of state regulation for water conservation and correcting its pricing. Currently the water price does not reflect its scarcity. It is instead valued at the cost incurred for maintaining water infrastructure and extraction borne by the farmer in the form of electricity bills. This comes down to a paltry PKR 135 canal water charges per year and PKR 3000 to 5000 per acre watering charges for electricity.

Construction of dams may not ensure an adequate water supply unless they also address the issue of water losses incurred due to faulty construction of both reservoirs and distribution infrastructure. Distribution network losses amount to 50 to 55 million acre feet (MAF) of water every year.

Policymakers must bear these points in mind before the construction of proposed Bhasha Dam, that can potentially store up to 8.5 MAF of water begins. Mr. Leghari added that Pakistan currently stores less than 10% of the water that flows compared to a global average of 40%.

Water management as a solution to water scarcity – Lessons from the Colorado river basin

Pakistan can learn from the significantly successful water management strategies deployed in the Colorado river basin. Dr. Sattar presented the findings of her extensive research on the basin highlighting lessons for Pakistan. The Colorado basin in America is currently undergoing a two-decade drought. Despite this, the US government has managed to increase both its agriculture productivity by 25 percent and its power generation by 30 percent. The US was able to do this by building consensus amongst all relevant stakeholders for implementing effective reforms, which is something that the Indus River System Authority (IRSA) in Pakistan has not succeeded in doing thus far. Dr. Sattar further shared that Indus river basin has 10 times more water in the system than the Colorado water system and yet Pakistan’s GDP is lagging massively behind.

The broad contours of the solution comprise rationalization of water use, especially for agricultural purposes, which can happen through adequate costing of water and will prompt higher productivity per each drop of water. Crop zoning has proven crucial for conservation of water. Demand management, through mobilizing extra cubic meters of water – and not dams – remains the cheapest per liter source of water.

Latest policy response on water mismanagement in Pakistan

A National Water Policy 2018 has been formed, which has determined the key priorities on which the newly formed water commission, run by Federal Ministers, will urgently work towards. To this end, a coordination body has been assembled for tackling the multifarious issues pertaining to water mismanagement by bringing all stakeholders on board for political ownership. This is a similar model which was followed by the US government for the efficient utilization of water from the Colorado river basin despite the seemingly unsurmountable challenges they faced. Their institutional coordination included all political and private sector influencers in the matter from the highest to the lowest echelons relevant for contributing to the solution. That level of transparency and fervent intention is what needs to be replicated in Pakistan for sound implementation of the identified priorities.

Sharmin Arif is the Communications Associate at the Consortium for Development Policy Research.