There is a pressing need to distinguish between causes and outcomes in Pakistan’s ongoing power crisis. Power shortages (i.e., a shortfall between peak demand and supply) remain a headline outcome, and one determined by several causes. However, these causes have not received sufficient attention from policymakers, who, in turn, continue to focus on the outcome itself. This has created a situation in which interventions are misplaced, and the structural roots of the crisis stand unaddressed.

Let us briefly look at the causes.

I would envision any well-functioning sector to have an appropriate policy framework as its foundation, adequate funding to build on that foundation, and strong governance to implement and manage its prescriptions. Sadly, Pakistan’s power sector has lacked all three elements, as a result of which the sector has suffered through decades of ad hoc and crisis-driven policy making.

High dependence on imported oil has raised generation costs for power utilities, rendering them unable to recover costs through tariffs. This is partly because the government refused to raise tariffs during 2003 and 2008 when generation costs were rising sharply. Issues of high Transmission and Distribution (T&D) losses, non-payment of bills by consumers and delays in payment (or non-payment) of allocated subsidies have added to the financial fragility of utilities. All of this has resulted in insufficient investments in power infrastructure because of which existing plants have been forced to operate beyond their capacity, thus making them age faster and risking frequent breakdowns. Matters have also been made worse by government’s reluctance to move aggressively with sector reforms, including privatization. Consequently, power shortage has gone up, imposing prolonged power cuts across different types of customers.

But is there a cure-all solution?

Just as multiple issues have caused the problem of power shortage, only multiple solutions can address these issues. One of these solutions can be net metering.

What is net metering?

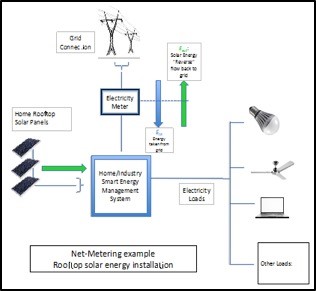

Usually, electricity flows the grid to the consumer. But this does not mean that it cannot flow in the opposite direction, i.e., from the consumer to the grid. Let me explain how. A consumer can produce her own electricity, typically from rooftop solar installations, and feed it back to the grid. This technical innovation will require that the flow of electricity from the grid to the consumer and from the consumer to the grid are both measured separately and the consumer is billed according to a net tariff, representing the difference between the cost of electricity purchased from the grid and the price of electricity sold back to the grid. Thus net metering represents the net bill for the electricity taken from the grid. In extreme cases, consumers can feed more electricity to the grid than what they take from it, in which case they will be paid by the distribution company for the surplus electricity produced.

Figure 1: How net metering works

Source: raftaar, 2016

National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA), which is the national regulator, passed the “Distributed Generation and Net Metering Regulations 2015” in September 2015. This was a significant breakthrough, as today Pakistan is among the 110 countries in the world that have policies for net metering.

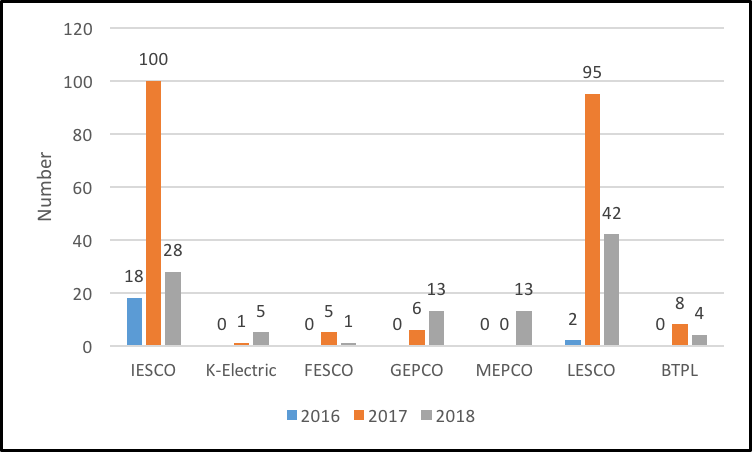

Figure 2: Net metering licenses given out by all Distribution Companies (DISCO’s) in Pakistan (2016-2018)

Source: NEPRA

How does it speak to the issues mentioned above?

Net metering is a cost-effective solution because it 1) has low set-up costs and 2) it uses free sunlight for generation. Centralized power plants, on the other hand, require huge investments to set up and depend on expensive oil for power generation. According to recent research by the University of Punjab, the rooftop space available at the Punjab Government Servants Housing Society in Lahore was able to accommodate enough solar panels to produce nine times the amount of electricity needed by the entire housing society. Domestic consumers are about 86 percent of the total electricity consumers in Pakistan, so one could imagine the kind of savings that can be made if net metering was scaled up.

The recent use of smart meters in Pakistan has revealed that longer feeders – wires that transmit electricity from grid stations to consumers – result in higher T&D losses. This is primarily because of bad equipment, poor maintenance and energy theft. Net metering can revolutionize existing power distribution by bringing electricity generation on-site or near-site for consumers. This would drastically reduce T&D losses.

Although net metering may not fully resolve the issue of low recovery rate, it may still be able to yield some improvement. Net metering reduces a consumer’s bill because 1) she uses less electricity from the grid as she is now producing her own and 2) she sells surplus production back to the grid. Reduced bills mean that these consumers are more likely to pay their monthly bills, especially because they are now also expecting payments from the distribution companies (DISCOs).

Way forward

In order to tap the full potential of this technological innovation, there is a need for it to be scaled up across domestic and commercial segments. For this, a partnership will be required between DISCOs (for their on-bill payment network) and commercial banks (for financing for upfront equipment costs). This suggestion is both practical and realizable in Pakistan’s context, e.g., in the gas sector, the Oil and Gas Regulatory Authority (OGRA) has allowed the Sui Northern Gas Pipelines Limited (SNGPL) to finance Solar Water Heaters (SWH’s) utilising its on-bill payment network. Therefore, following its disruptive, positive policy regulation that has allowed net-metering in the country, perhaps NEPRA should next also allow on-bill payment financing schemes for net-metering. The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) has already set the wheels in motion by announcing a credit facility to finance renewables through commercial banks, so NEPRA will be adding to the momentum. While this will be a good step forward, it will be critical to ensure that only high quality, verified solutions are allowed once a market for this promising technology has been created.

Usman Naeem is a Country Economist at the International Growth Centre (IGC).