This blog post is based on a session of the Lahore Policy Exchange, titled “Lahore’s Future” held at the Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR) on June 12, 2024, with Dr. Ijaz Nabi, Dr. Sanval Nasim, Dr. Mohammad Omar Masud, Ms. Qudsia Rahim, Ms. Imrana Tiwana, Mr. Omar Hassan and Mr. Kamil Khan Mumtaz.

Once a Walled City, with thirteen historical gates as its entry points particularly during the Mughal era, Lahore has expanded rapidly and is turning into a multicentric megacity, with a population of around 14 million people. The city has multiple business centres, including Raiwind, Defence Housing Authority (DHA), Gulberg and Mall Road. Several infrastructure projects, such as the Orange Line transport system, Lahore Ring Road and the signal free corridor initiative, have revamped the city’s outlook.

A large number of people move to Lahore every year, further expanding its boundaries horizontally and intensifying the demand for housing. To meet this demand, high-rise apartment buildings and self-sufficient housing societies, such as the Askari apartments, the new phases of DHA, Paragon City, Bahria Town and Lake City, have emerged in Lahore’s peripheries, making the city’s original boundaries increasingly unclear.

This blog focuses on the blurring boundaries of a metropolitan city like Lahore that has grown manifold in the past few decades and explores the social and environmental consequences of haphazard and unsustainable urban growth. It also highlights the need to have a consolidated approach for Lahore’s urban development.

Sprawling growth is unsustainable

Lahore currently has four main agencies looking after various segments of the city, namely Lahore Development Authority (LDA), Lahore Municipal Corporation (LMC), the cantonment board, and DHA. Despite multiple players, Lahore’s sprawling horizontal growth appears to be largely unplanned, unchecked and ungoverned. This urban sprawl is unsustainable as it not only encroaches on productive farmlands and villages but is also detrimental to the city’s natural resources, and a burden for the city administration in terms of provision of amenities including road network, clean water, sanitation, and infrastructure.

Let’s take a look at some of the challenges that Lahore is facing due to its blurring boundaries:

Smog as a permanent feature in Lahore’s cityscape

Lahore’s streets are always bustling with an unparalleled energy. Its colourful bazaars are crowded with street hawkers who offer an array of items – from delicacies to ethnic jewellery, and handwoven fabrics. The magnificent Wazir Khan Mosque, the grand Badshahi Mosque, and the glorious Shalimar Gardens are heritage sites that speak of an era of luxury, long gone but not forgotten. Now, an unfortunate addition has become part of the cityscape; smog veils the city’s cultural sites and business centres for most part of the year, blurring its vibrance and dulling its beauty.

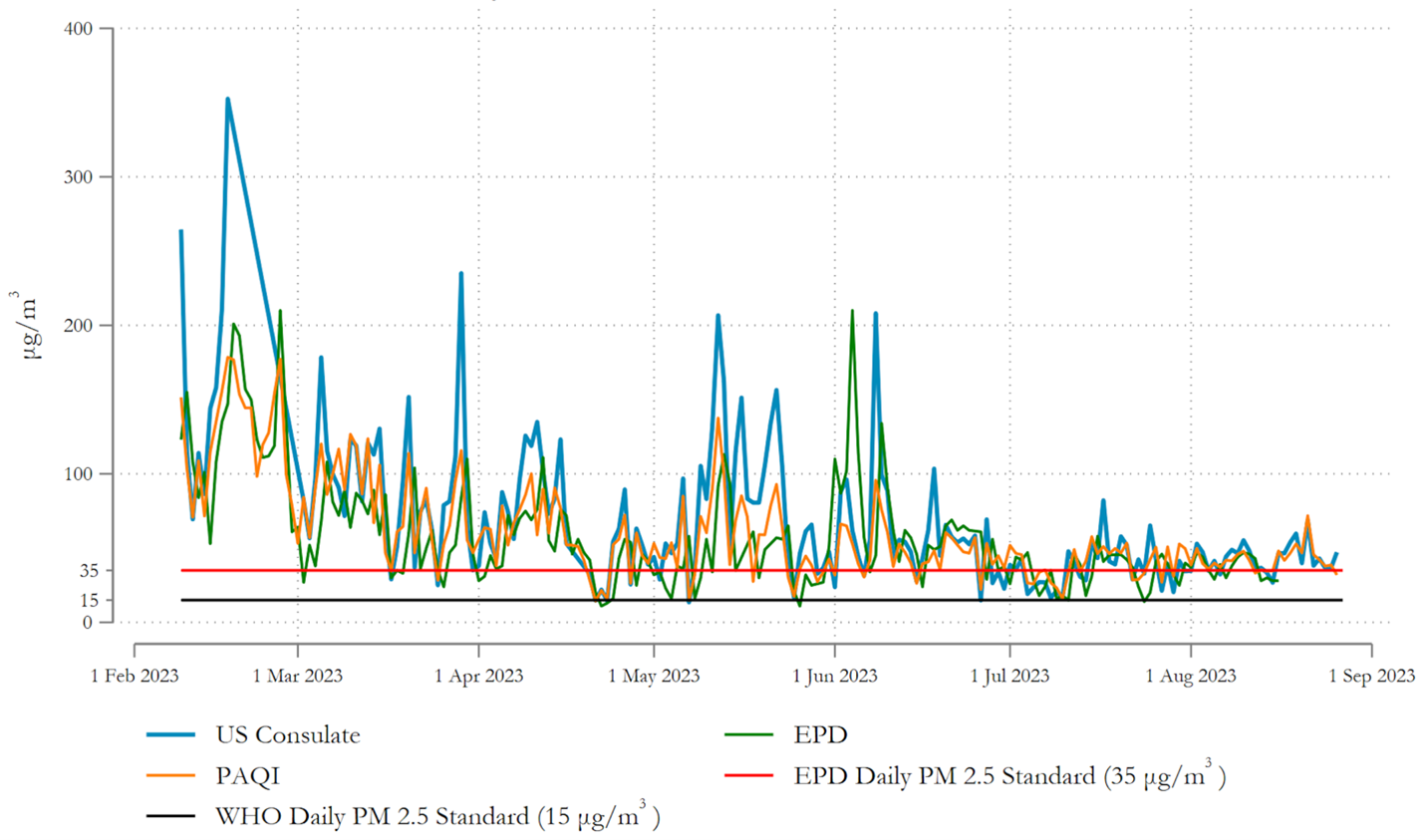

Lahore has been repeatedly ranked as one of the most polluted cities in the world with declining air quality as a result of an increased number of vehicles on roads, high levels of industrial activity, emissions, and waste burning. Studies now show that the average age of a citizen of Lahore has declined by seven years due to poor air quality. Breathing in Lahore’s air has also been compared to smoking around thirty cigarettes per day!

The cost of Lahore’s urban sprawl is also evident in terms of environmental degradation. The city of gardens, once in bloom, with a clean River Ravi flowing through it, is now losing its tree cover, due to rampant construction. Roads, highways and underpasses, while ensuring connectivity and economic growth, are also contributing to increased emissions.

Urban stress for the average citizen

It is not uncommon for Lahore’s residents to experience traffic congestion almost every day. The honks of impatient commuters add another layer to Lahore’s sounds, with buses, cars, and trucks inching forward, leaving little room for pedestrians to move. This leads to high levels of stress, prevalence of depression and low self-esteem among citizens.

The rising temperatures and unpredictable weather conditions bring about urban flooding every year. Low-lying areas in Lahore, including Gulberg, Garden Town and Township, are submerged underwater after heavy rain, and with the city’s weak sewerage and drainage system, it takes days for rain water to clear, restricting mobility of residents, causing traffic congestion as well as electricity breakdowns, hence bringing economic activity and the daily course of life to a standstill.

Outbreaks of waterborne diseases like cholera and typhoid are also common after heavy downpour and flooding. Other issues such as untreated industrial waste, falling groundwater levels and contaminated water also emerge as health hazards that are likely to exacerbate if left unaddressed.

Sprawl and slums

The signs of inequality in Lahore are now more visible than ever. In recent years, ineffective coordination between federal, provincial and local government departments and lack of prioritisation for efficient urban growth has led to haphazard expansion of the city, where developers have leaped over massive patches of land to acquire cheaper land far from the urban centre of Lahore. With the city expanding without a plan, informal settlements have started to form around city limits and within the city, particularly near construction sites, under bridges and outside gated communities. Slum dwellers lack proper food and sanitation facilities, and the likelihood of drug addiction and crime in areas around slum settlements is also high.

Defining boundaries

Imagine a well-connected, walkable Lahore with pedestrian-friendly streets, where people can walk freely and comfortably without any mobility constraints and where amenities are accessible with ease. The sidewalks are lined with trees to provide shade for pedestrians and the traffic is managed efficiently.

While such an image of Lahore might appear to be inconceivable, it is indeed probable through a proactive approach of policymakers and leaders, and a normative mindset of the community:

Public sector’s role in setting boundaries

Having multiple players managing a city’s urban development can lead to fragmented policy-making and conflicting interests, and can be largely detrimental to the city’s overall growth and the well-being of its people. The role of government is hence crucial in adopting an integrated approach to ensure sustainable urban growth, curbing urban sprawl and preventing leapfrog development. It is now more important than ever to use a data-driven approach to set city boundaries and manage the city’s limited resources more efficiently.

Lahore needs a unified urban voice

For Lahore to have a normative future where its unplanned urban sprawl is curtailed and managed, a unified urban voice is the need of the hour, integrating efforts of all agencies responsible for its urban planning and providing a space for civil society, citizens, academia, and other relevant stakeholders, to interact and participate in policy-making.

Developing cities around Lahore

A holistic urban vision for the city will also allow stakeholders to prioritise the development of Lahore’s neighbouring cities such as Gujranwala, Sheikhupura and Kasur so that more economic opportunities emerge for the people residing in those cities. This approach will also control the influx of population entering Lahore every year, hence keeping a check on Lahore’s annual average growth rates.

Empowering citizens and the civil society

An empowered community can play a pivotal role in devising and implementing an urban strategy that will define clear boundaries for Lahore. Such a strategy will prioritise accessibility, walkability, sustainability and preservation of its heritage sites as major pillars of urban development.

Making the city of gardens green again

The cultural capital of Pakistan has been known as the city of gardens, but the loss in tree cover is a disturbing truth that requires immediate attention and action. Urban planning needs to account for greener spaces in the city so that Lahore lives up to its title.

Faiza Zia is a Programme Manager at the Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR).