Among the greatest of COVID-19’s ravages is its impact on the already-struggling education sector in Pakistan. Since March 2020, schools have either been completely closed, or have operated under COVID restrictions. While the federal and provincial governments have opted to televise curricular content, the prolonged closure of schools has seen profound learning losses and an increase in drop-outs. For Pakistan, a country with a literacy rate of around 60 percent, this has dire long-term consequences that the government needs to address. In the absence of access to alternative learning modalities, the closure of schools has given rise to learning losses which are considerably greater for students belonging to marginalised groups.

The Digital Divide

Faced with the need for home-schooling options, the federal and provincial governments decided to air curricular content for K-12 (kindergarten to 12th grade) through television, as part of the TeleSchool and Taleem Ghar programs, given that it is the most widely accessible medium of communication. However, according to Pakistan’s Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) conducted in 2017, only about 15 percent of households of the poorest quintile owned a television. Comparatively, within the wealthiest quintile, around 96 percent owned televisions. In addition to this, many teachers across Pakistan have relied on the use of smartphone technology through WhatsApp to relay important information to their students, but access to the internet and smartphones is even more unequal. Only 12 percent of the households surveyed had access to the internet. These figures become more complex considering their dispersion across rural/urban settings. While 22.9 percent of urban households had access to the internet, only 4.9 percent of rural households had the same. Pre-existing inequalities have translated into limited access to fundamental learning tools, exacerbating the problem.

A report by the World Bank estimates that 930,000 students will drop out from both primary and secondary education because of the pandemic. This is in addition to the 20 million-odd children who are already out of school.

Figures aside, even within households that have access to television or the internet, how likely is it that these would be primarily dedicated to a child’s education? In a household where multiple people rely on one smartphone, it is likely that the phone will be used for other things considered more essential, such as employment purposes. At a broader level, even if there is some access to technology, how conducive are home environments to education? Many children in rural households are actively engaged in farm labour, and even within urban households, children are expected to engage in household chores. Compounded with incidences denoting the rise of violence at home, these facts present a grim picture for home-schooling in Pakistan during the pandemic.

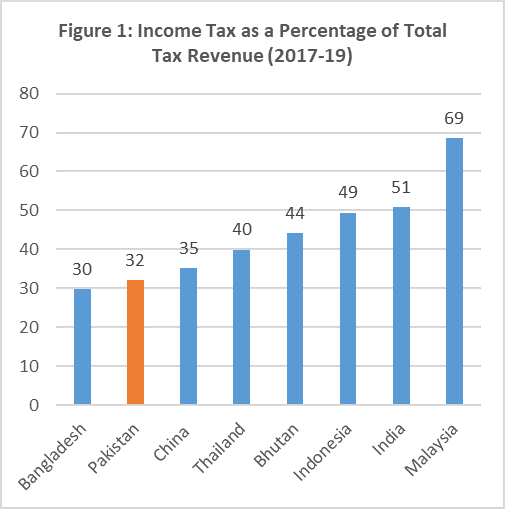

Source: World Bank (2020)

Gendered Impact

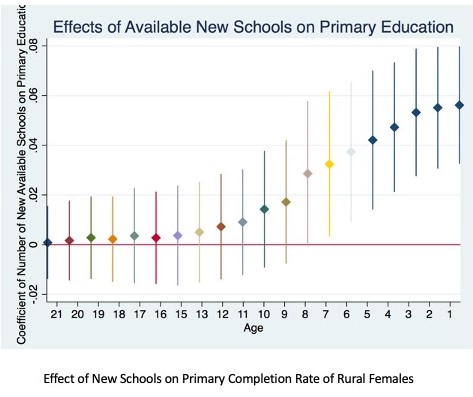

The closure of schools has had a pronounced impact on girl’s education. Already, 50 percent of women in Pakistan receive no education to 34 percent of men (DHS, 2017). During COVID-19, this situation has worsened because girls are usually tasked with the responsibility to provide domestic help. Moreover, girls are more likely to be excluded from access to technology making remote learning even more difficult for them. The burden of care, coupled with a lack of access to essential learning tools means that it is likely the number of out-of-school girls has, and will continue to increase substantially. It is also likely that faced with income losses during the pandemic, some students may be forced to drop out of school and work. In such cases, girls are the first to be taken out of formal educational institutions.

Lessons Learned

CDPR recently conducted a webinar reflecting on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on education and the responses adopted by the government, civil society and private institutions. As discussed before, the differential distribution of information technology in Pakistan meant that some students could not be reached through television or other digital platforms. In the absence of avenues for communication, TCF schools and the Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi (ITA) rushed to gather students’ contact information a week before schools were set to close in March 2020. The ITA also gathered information about students’ access to different media, to gauge their response if schools were to be closed for a prolonged period of time. To combat the gap in communication, TCF published a low-cost magazine to encourage student engagement, and relied on community-based learning modules. The ITA liaised with parents and local communities, and with the help of teachers, set up similar community-based spaces for learning for girls. An overarching collaboration between the government, civil society, the private sector, teachers, parents and the larger community forged enduring connections that have proved to be crucial at this time of crisis.

The Way Forward

Looking forward, how can the government improve its response towards education during the pandemic? A blog by Dr. Rabea Malik highlights the need for understanding the multiple ways students have experienced learning losses during the pandemic: potential learning that was lost due to the closure of schools, low-performing students that have fallen further behind compared to well-performing students, and an increase in the number of drop-outs. To ensure that any policy takes account of the inequalities mentioned above, she suggests a three-pronged approach. The government must make use of the Management Information System (MIS) already in place to collect data about at-risk students. It must also plan a large-scale campaign to re-enroll students after schools open and have a system to assess children to provide remedial instruction. Accomplishing these tasks would require a capacity for data collection and its utilisation, as well as provision of teacher training and support at the district and provincial levels. It would also require flexible financing options and a structure that connects small clusters of schools to higher tiers of governance.

If such policy measures are not adopted, Pakistan’s already-struggling education sector will face long-term consequences. Article 25A of the constitution guarantees free and compulsory education for all citizens aged 5 – 16, yet Pakistan has a long way to go before achieving universal enrollment. It is estimated that Pakistan’s Learning Poverty, which is a metric that quantifies the number of children who will not be able to read and understand a simple text, will rise from 75 to 79 percent due to the pandemic. While this has consequences for students’ eventual integration into the job market, that shouldn’t be the only thing of concern. Education can be a vehicle for equity and greater social cohesion, and when it’s missing, poorly delivered or unfairly distributed, a vehicle for injustice and greater social exclusion. It is also a way of inculcating civic skills that allow meaningful participation in civil society and political life. Losing such a large section of school-going children has direct consequences not just for the economy, but for political and social order.

Zohra Aslam is a Communications Assistant at the Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR).