There is little doubt that a changed world awaits us on the other side of COVID-19. The contours of what these changes will look like, and their magnitudes, will depend largely on how we diagnose not only how the pandemic started, but also how we responded to it. With breakdowns in global supply chains, will countries adopt more insular economic policies? Or will they recognize the benefits of a trade system that allows risk pooling? As more and more people change not only how they work, but also how they interact with society, questions have been raised about how many of these changes will last beyond the pandemic.

Perhaps the most harrowing feature of the pandemic is not that it brought the global economy to a virtual standstill, but that it has taken on a uniquely urban outlook. In that respect, the corona virus is not just a threat, it is a uniquely urban threat. With social distancing, self-isolation, and quarantine becoming the norm over the past few months, it has forced us to turn inwards and left us bereft of the physical contact and proximity to others that define modern city life. Many cities have been forced to confront the reality that what made cities great previously, is now the very thing that has made them vulnerable to the pandemic.

It is far too early to talk about the lessons that can be learnt from the corona virus while the world still struggles to fight the pandemic, but there are three key questions that we need to focus on, even as the fight continues, to enable us to make better decisions in the future. First, how did the pandemic start? We know that the blame largely falls on poor sanitary standards in China’s wet markets. There will undoubtedly be renewed pressure in the future for countries to improve health and safety regulations. Second, how did the virus spread? And third, how did governments respond to the crisis? It is the latter two questions that have occupied policymakers since the outbreak, and will continue to be the subject of much research in the times to come.

In the midst of this, commentators have been quick to single out the enemy: urban density. In an article in the Washington Post, Joel Totkin says: “Just as progressives and environmentalists hoped the era of automotive dominance and suburban sprawl was coming to end, a globalized world that spreads pandemics quickly will push workers back into their cars and out to the hinterlands.” These opinions have been echoed by Governor Andrew Cuomo of New York, who in a tweet urged New York City to rethink and reduce density.

Similar concerns about density were also voiced in Pakistan and other low-income countries. If the pandemic were to strike one of Lahore or Karachi’s hyper-dense low-income localities, how would we track its spread, carry out testing, and quarantine areas if necessary? According to research undertaken by the Karachi Urban Lab across 13 informal settlements in Karachi, plot size per household averages 20 square yards. Each household has an average family size of eight to nine people. In places where buildings have expanded vertically, household sizes go up to 30 people per 80 square yards. The people who live in these informal settlements lead precarious lives with respect to their health and safety under the best of times. In times of a pandemic, this risk is heightened to an extreme extent.

Linking urban density with a city’s vulnerability to epi- and pandemics may seem like an obvious and appealing connection. The sheer frequency of interpersonal contacts, whether in public transport or in cramped living spaces, makes people more susceptible to viruses. New York City is an oft quoted example with a population density of over 26000 people per square mile. As of 30th April, the City had reported over 167,000 confirmed cases of the corona virus and nearly 13000 deaths. Numbers such as these add strength to the argument against densification.

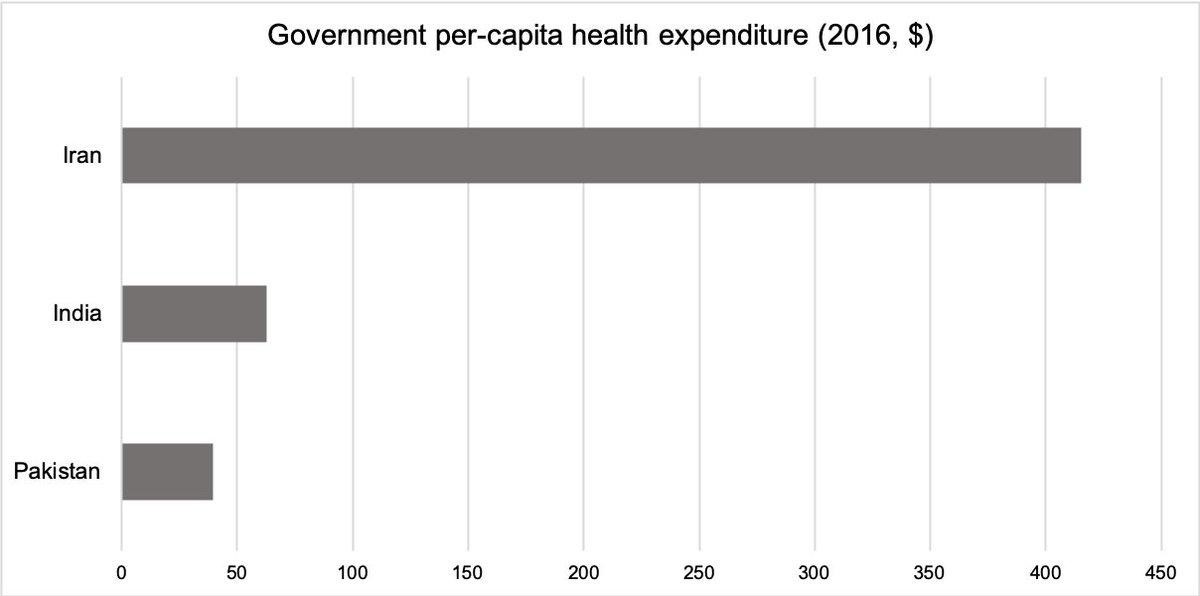

However, as straightforward as the argument against density may seem, it does not withstand closer scrutiny. While there is no doubt that density has had a role to play in the spread of the pandemic, it is important to remember that density is just one of several factors that determine how vulnerable a city is to the pandemic. Equally if not more important are the quality and accessibility of healthcare systems, the fiscal resources available for disaster management, the organizational capacity of city governments, and the timeliness and effectiveness of other policy responses.

Cities like Singapore, Seoul, Shanghai, and Hong Kong, which are extremely dense in their own rights, have out-performed many other less dense cities in containing the virus. Even within the United States, there are marked differences between rich dense areas and poor dense areas. Montreal’s Plateau District has a density of 32,598 people per square mile, higher than the New York City average. Towards the end of March, the district had reported less than 500 cases. In China, cities with the highest coronavirus infection rates were those with relatively low population densities, in the range between 5,000 to 10,000 people per square kilometer.

It is possible to look at this data and think that Singapore and Seoul are wealthy cities as is, with more resources at their disposal, which could be mobilized as soon as the crisis started. This is true. But while correlation does not imply causation, dense cities are more efficient and productive, and hence more wealthy.

Simultaneously, the global spread of the disease also merits further research. The obvious culprits in this case are global cities, busy airports, and global supply chains. With so much connectivity, of course we have a world-wide pandemic. However, there is another story at play here – one about non-global cities, about suburban and peri-urban areas and industrial linkages. This is what the experiences of Germany and Italy tell us.

As complex and difficult as the crisis is, the debate on our urban future comes at the right time. Climate change has already forced us to rethink urbanizations and city life. All future conversations on cities will now need to be had in the context of climate change and sustainability, as well as global pandemics. Perhaps a thin silver lining to come out of the pandemic is that it has put every country and city to the same test. In that respect what researchers have access to is a depth of material to study in an attempt to understand which policy responses worked best, which governance models were most effective, and crucially, what role city density played in the spread, or mitigation, of the disease.

With pressure on Pakistan’s cities to densify and grow upwards, we would do well to learn from these debates in order to chart out a course that would create the best outcomes for our cities and citizens.

Why Density?

The most important thing we must remember is that density in and of itself is not the enemy. The experiences of the East Asian cities tell us as much. The benefits of urban density include better public transport, more affordable housing, better health care facilities, more efficient energy usage, and improved diversity, safety, and vibrancy – all things which give a city its character. As Brent Todarion says, “Density done well should be a design-based approach to responsible city leadership, flowing from a city’s vision and values.”

Moreover, the effects of other policy responses notwithstanding, urban density can have significant positive impacts on healthcare provision in a crisis.

What we should be thinking about now is how has density been done so far? Typically, density has been clubbed into two categories: 1) high density, low-rise, and 2) high-rise, high density. Both types are controversial. While the former brings to mind images of hyper-dense low-income localities, the latter describes an area like Manhattan. In times of a pandemic, both are dangerous. The first comes with smaller accommodation sizes, forcing people closer together. The second has elevators, corridors, and other common spaces, which increase the probability of interpersonal contact.

What the pandemic has shown is that we need to think more and more about what has been called the Goldilocks density. This means that cities need to be “dense enough to support vibrant main streets with retail and services for local needs, but not too high that people can’t take the stairs in a pinch. Dense enough to support bike and transit infrastructure, but not so dense to need subways and huge underground parking garages. Dense enough to build a sense of community, but not so dense as to have everyone slip into anonymity.”

Density, however, does not work in isolation. In order for it to be done well, cities need strong governance structures, robust infrastructure to support it i.e. transportation, waste management, sewerage, and utilities, revenue streams to finance it all, as well as innovative urban planning and design. For Pakistan, this would mean creating empowered local and city governments and a decentralization of resources, as well as investments to build the capacity necessary to create these institutions. Strong local and city administration would give governments the infrastructure and capacity needed in times of a crisis such as this, when the local level becomes the most efficient spatial unit to manage survival (read more here).

Healthcare, density, and pandemics

Perhaps the most significant benefit of dense urban localities is that it makes tracing the contagion much easier. In dense localities, a significant portion of a person’s interactions may take place closer to home, resulting in geographic clusters of the disease that can be tracked and quarantined. In more spread out living arrangements, interactions take place over much larger areas. This makes contact tracing and containing the transmission chain much more difficult.

It is also true that some public goods, such as public transportation and healthcare, only become viable at scale. What this means is that a secondary or tertiary health care facility would only be feasible if a minimum number of people lived in its immediate vicinity. In the event of a pandemic, we need to think about where the doctors and facilities are and where the people live.

With more people living close to each other, it is also easier to scale up and improvise by using alternative venues like theaters and convention centers as field hospitals.

Long-term planning

The corona virus has further highlighted existing inequalities that exist in our society. Many have called the virus the “great equalizer”. While the virus may not discriminate between rich and poor, its effects do. As such, not all people experience the pandemic in the same way. Lockdown for a family living in a 200 square yard house is vastly different from one living in a bungalow in Defense or Model Town. In this article, the Karachi Urban Lab has already highlighted the differences in how the pandemic is experienced across different income classes. These differences include unequal access to water, income, employment, healthcare, and food among others. While the lockdown debate has focused on lost incomes, the majority of Pakistan’s informal settlements are water deprived. For people living in these settlements, using water repeatedly to wash their hands is a luxury they cannot afford. Similarly, the majority of these people also work in the informal sector as daily wagers and are the most vulnerable to lockdowns. Losing even one day of earnings means not being able to feed their families.

In the absence of a robust and well-established social protection mechanism, the government is faced with the herculean task of controlling the spread of the virus, while ensuring people in lower income segments have access to healthcare, food, and other basic sustenance. Public policy is difficult in the best of times. A crisis such as this puts the entire government machinery, as well as society, to the test.

The uniquely urban nature of this crisis should serve as a wake-up call for urban planners, bureaucrats, and policymakers in Pakistan. Our urban planning has been unsustainable, inefficient, and too anti-poor for far too long. Going forward we need to ensure more equitable distribution of resources and more equitable access to urban infrastructure. One metric to measure the scale of the disparity is ownership of land. According to a 2019 study by the Urban Unit in Punjab, in all recognized housing schemes in the province, about 68% of plots lie vacant and 10% are under construction. These plots are owned primarily by the urban upper-classes. While on the one hand residents of informal settlements are cramped into multi-generational, small living spaces, on the other we’ve surrendered vast swathes of our cities to the upper-classes. The poor have been pushed to the margins and the peripheries. This is both unproductive, and quite simply, wrong.

Bakhtiar Iqbal is a Research Assistant at the Consortium for Development Policy Research (CDPR) with an interest in urban planning.

Sources of information

Sources of information