This blog is part II of a two-part series, based on the findings from an assessment conducted for UN Women, of how the COVID19 pandemic is likely to impact existing gender inequalities in Pakistan. Part I of this series focused on how COVID-19 has exacerbated gender based economic inequality. This part will focus on the social costs of the pandemic for women in Pakistan.

It has now been over six months since the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Pakistan. The virus, and resultant efforts to control it, have had significant and far reaching socioeconomic consequences, many of which are only just becoming apparent. As discussed in our previous post, vulnerable communities such as women are most likely to be the hardest hit. As primary caregivers, women and girls face an increased burden of responsibilities within the household. They a) are responsible for household-level disease prevention and response efforts, which puts them at a greater risk of infection, b) carry out most of the household’s chores, c) are subject to emotional, physical, and socioeconomic harm. This post will discuss some of the social consequences of COVID-19 on women. Specifically, it will focus on the how the virus and the resultant lockdown has affected domestic responsibilities and gender-based violence (GBV).

Implications of Changes in Domestic Responsibilities:

Women tend to lack agency over their decisions, their movements, and even how they use their time. The division of domestic labour is very gendered, and the general expectation is that domestic responsibilities are the purview of women. According to UN Women, before the pandemic, women globally did nearly three times as much unpaid care and domestic work as men. During the lockdown, this disproportionate burden has increased even further. With entire families at home all day, basic domestic responsibilities – such as cooking and cleaning – have increased, which women are expected to fulfil. Additionally, in households with school going children, the entire burden of home-schooling is being handled by mothers.

This increase in responsibilities will have a long-term impact on women’s physical and mental health. The most direct way this impact manifests is that many women will simply not find the time to go out for even basic health services. Reduced mobility also directly limits access to health care for women, worsening health outcomes in the long run. Increased workloads at home coupled with a reduction or loss in income are likely to raise stress and anxiety levels for women, leading to deteriorating mental health as well.

Female labour force participation will also decline as in the face of increased domestic responsibilities. Similarly, as their involvement in household work increases, it is possible that fewer girls will return to schools once they reopen, leading to a larger increase in school dropout rates for girls as compared to boys. This will result in a decrease in female education attainment and reduced female labour force participation in the long run as well.

Lastly, increased proximity of households to each other, coupled with decreased mobility and heightened stress, is likely to result in increased domestic gender-based violence. This is discussed in detail below.

Gender-Based Violence (GBV):

According to an April 2020 research conducted by Columbia University, gender-based violence increases during public health emergencies. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a distressing trend witnessed globally in the increase in domestic violence against women, or violence perpetrated against women by an intimate partner. In France, for example, cases of domestic violence have increased by 30% since the lockdown on March 17. Helplines in Cyprus and Singapore have registered an increase in calls by 30% and 33%, respectively. In Argentina, emergency calls for domestic violence cases have increased by 25% since the lockdown started (Source: UN Women).

The circumstances created by the pandemic and the prolonged lockdown create – and in existing cases heighten – instability and volatile domestic situations, which are a threat for all vulnerable groups, specifically women and children. Economic pressures and tensions in households have increased, which can often act as triggers for domestic violence. In many cases, with reduction in household incomes and higher living costs, the triggers for short tempers or violent behaviors go up. As these pressure points get aggravated, incidences of verbal and physical abuse also rise.

In Pakistan, up to 90% of women face some form of domestic violence – physical, emotional, or psychological – at the hands of their husbands or families (UNODC 2020). Violence against women, which is generally a taboo topic to talk about in our culture, has increased significantly during the lockdown period. According to helpline data released by the Punjab Unified Communication and Response (PUCAR-15) domestic violence calls have increased by 25% during the lockdown period in Punjab alone.

State responsiveness to reported complaints of violence has reduced even more than before, with the response system burdened or redirected elsewhere. For example, the Ministry of Human Rights created a helpline (1099) for reporting domestic violence incidents during the pandemic, but this helpline is reportedly not fully responsive. Additionally, complete or partial lockdowns reduce informal spaces of safety for vulnerable segments. Options of interim relief time and space (for example when an abusive partner goes to work) dry up as well.

Policy Implications:

With COVID-19 death rates – somewhat unexpectedly – falling, the lockdown throughout the country is being eased, and there is a gradual return to business as usual. However, there is still reason to be cautious, as there is little clarity regarding what has curbed the spread of the virus. The possibility of a resurgence and consequent lockdowns remains on the cards for the foreseeable future. Realistically, a vaccine will not be available globally for the next 12 to 18 months. As uncertainty and stress remain rife, and people struggle to adjust to this new normal, women will continue to be at a greater risk for violence.

It is therefore imperative for governments and policy makers to prioritize vulnerable groups and their protection. Specifically, as schools look to reopen in September, the government – with the support of the private sector and civil society organizations – needs to ramp up efforts to ensure that girls return to schools. This can be achieved through mass and social media campaigns highlighting the importance of schooling and the long-lasting impact of denying girls their right to a proper education. Additionally, information campaigns coupled with monetary incentives can ensure regular attendance of middle and high school girls, who are most likely to drop out to earn money to offset losses during the lockdown and the peak of the pandemic.

It is also important to change gender norms, and normalize boys and men being equal partners in domestic responsibilities. Equitable division of household labour is critical to reducing the burden on women and protecting their physical and mental health.

Lastly, support systems need to be established and existing systems need to be revitalized for those looking to report or escape a violent domestic situation. There also needs to be more awareness about potential avenues for help for victims of violence, such as the 1099 helpline.

There is tremendous uncertainty around the long-term impacts of COVID19 on the world. As such, policy priorities will remain focused on health and economic impact of the virus for the foreseeable future. While that is understandable, it is also imperative that gender not be considered a periphery of the pandemic. Long term policy responses to the pandemic need to be calibrated through a gender lens, to ensure the protection of women and girls.

Sahar Kamran is a Project Manager and Maheen Saleem Khosa is the Manager Communications at the Institute of Development and Economic Alternatives (IDEAS).

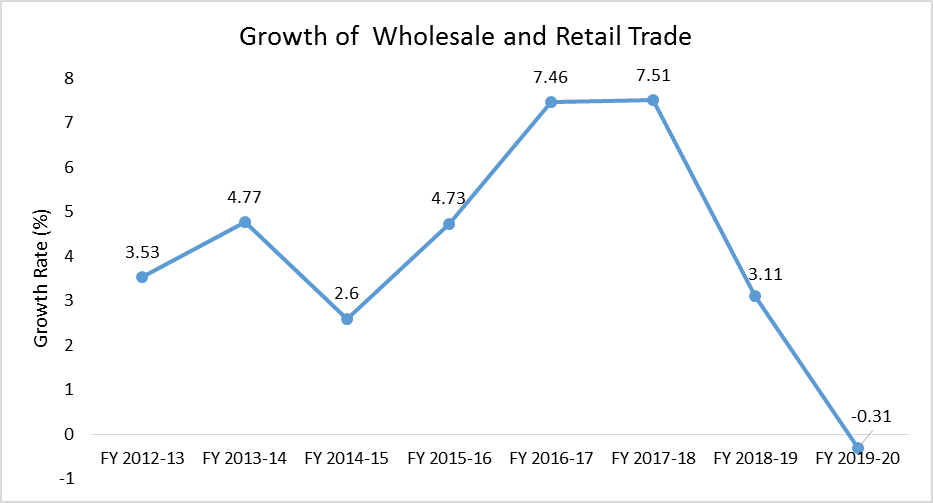

Source: Ministry of Commerce

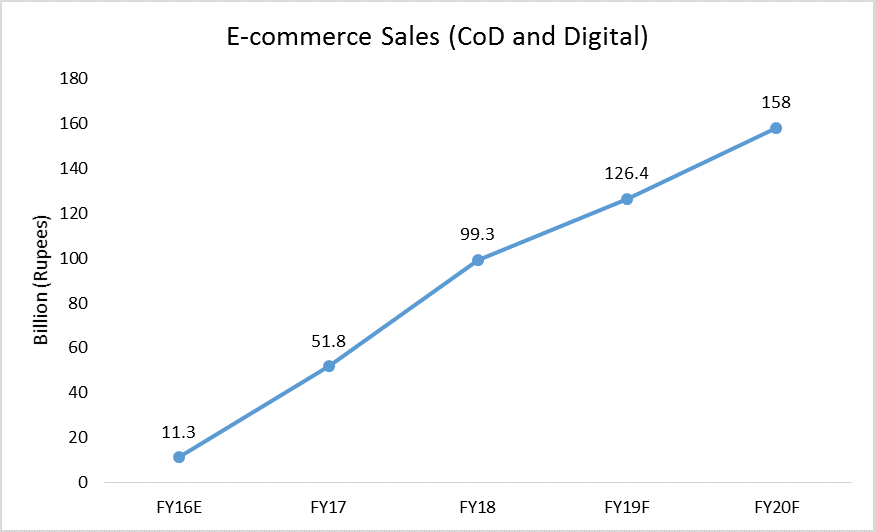

Source: Ministry of Commerce Source: DYL Ventures

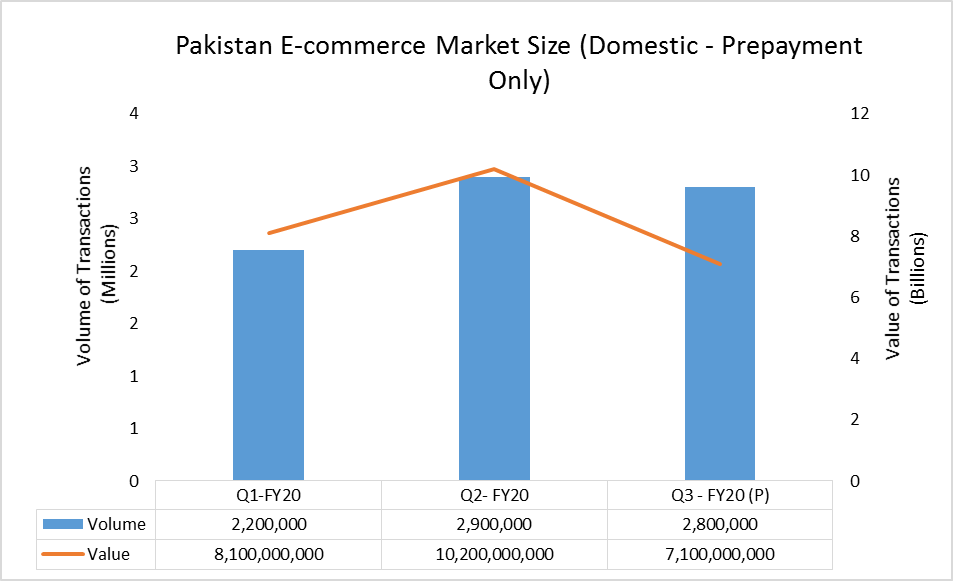

Source: DYL Ventures