With a rapidly growing urban population, Pakistanis are flocking to cities faster than any other country in South Asia. Resultantly, a fifth of all Pakistanis now live in just 10 cities.

By 2017, nearly 40 percent-up from 17 percent in 1951- of the country’s population was urban. As rural residents continue to move to cities in search of better prospects, Pakistan is projected to become an urban-majority country by 2030 with more than half of its forecasted 250 million living in cities.

If done right, urbanization can be transformative for Pakistan. International experience has shown that effective cities can become economic hubs and globally competitive drivers of growth. However, if misgoverned, unplanned cities can propel countries into discontent and further economic and political instability.

Urban growth without a shift in economic patterns can become non-inclusive (in service delivery) and unsustainable (if it does not create enough productive jobs). It can also lead to rising urban poverty. Hence, the country needs to formulate and pursue a strategy that guides urbanization away from its adverse consequences. The challenges here are as great as the failures of policy.

This piece looks at what lies ahead for urban Pakistan, its impact on the economy and a suggested way forward.

Urbanization Underpinned by Pakistan’s Demographic Reality

Pakistan is set to remain one of the world’s youngest countries for the foreseeable future. Almost 64 percent of Pakistanis are under the age of 30. Even by 2050, the median age is projected to reach just 31 compared with the current median of 22.5.⁴

This ‘youth dividend’ is a major growth opportunity, as well as a monumental policy challenge, for Pakistan. In a sense, some of the economic benefits of this demographic transition have already started accruing to the domestic economy. Over the past decade, growth in communications, consumer electronics, automobiles, education and retail sectors is evidence of market expansion driven by the youth.

However, youth unemployment is higher in urban than in rural areas. Of the 50 million people in the 18-29 year age bracket, 55 percent live in urban areas, with 30 million in Lahore and Karachi alone. Exploiting this dividend requires job-rich growth and increased productivity.

Urban Economy Landscape

When urbanization works, the economy expands faster as more people inhabit cities. To a certain extent, this holds true for Pakistan as it collects 95 percent of the federal tax revenue from ten of its major cities, with Karachi contributing 55 percent, followed by Islamabad at 16 and Lahore at 15.⁵ In fact, Karachi alone contributes around 25 percent to Pakistan’s GDP.

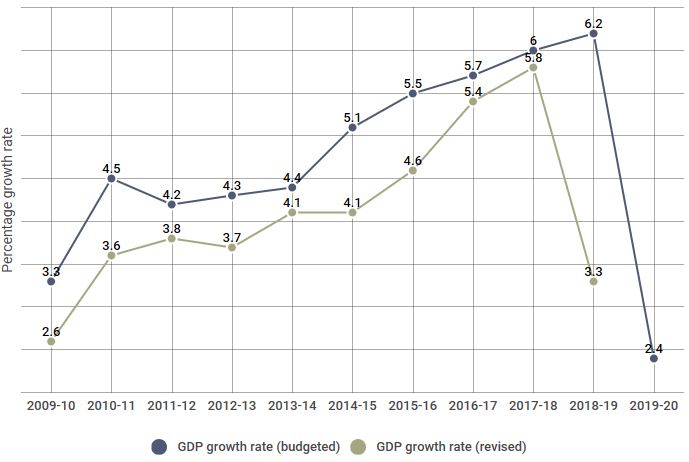

The share of the urban service economy is also larger than the national average. Since FY08, Pakistan’s urban economy has demonstrated an annual growth rate of almost 4.5 percent, compared to less than 2.5 percent for rural.⁶

Urban Pakistan generates almost 55 percent of the country’s GDP, even though only 38 percent of Pakistanis live in cities. This, however, falls short compared to other countries. India’s urban population is almost 10 percent smaller than Pakistan’s, but the country generates 58 percent of its GDP from urban areas.⁷ Similarly, for Indonesia, with 44 percent of its population in cities, 60 percent of its GDP is urban.

Pakistani cities vary in size in terms of their economy and potential to generate employment. The average urban per capita income among the top ten cities ranges from PKR 37,000 to PKR 70,000. Urban poverty has now also become a “major and visible phenomenon” .⁸ Six out of the top ten major cities have double-digit poverty figures: Quetta, (at 46 percent) has the highest poverty rate while Islamabad (at 3 percent) has the lowest .⁹

The continuous movement of people from rural to urban is linked to a shift in the economy. Services and industry remain major employment sectors in urban Pakistan while the share of agriculture in overall employment falls. The share of agriculture was down to 41.3 percent in FY18 from half in 1994.⁰ By FY16, the urban economy consisted mainly of services and industry with a share of 73 percent and 24 percent respectively. At the same time, the share of the national value added by sector in urban areas was 6 percent in agriculture (compared to 94 percent in rural), 58 percent in industry (compared to 42 percent in rural) and 63 percent in services (compared to 37 percent in rural). The widening urban-rural divide coupled with a decline in agriculture is expected to intensify rural to urban migration.

Cities create Economies of Scale

A higher concentration of people in cities grows the economy and boosts innovation. Denser economic activities create economies of scale. Larger market size increases productivity and creates knowledge spill overs.

Economists use a term called ‘agglomeration’ to describe this phenomenon. As economic activity takes place in close proximity to each other, businesses begin to specialize and offer services other rms lack. This specialization lowers production costs, attracts a diverse pool of labour, facilitates exchange of knowledge and skills, and spurs entrepreneurship. When clusters of such activity begin to form, they enable higher productivity and attract investment and innovation. In 2015, 22 percent of Pakistanis were residing in urban agglomerations of more than a million inhabitants.

Agglomeration, along with fast paced rural to urban migration, can provide increased manufacturing potential.⁴ Pakistan, however, has not yet benefited from this spatial transformation. This is evident in the poor performance of the industry that has failed to create well-paying jobs for those moving to urban centres.

Moreover, ill planned cities can also reverse economic gains. Pakistan’s urbanization has been termed as ‘messy and hidden⁵’Messy from the low-density sprawl and hidden as cities grow beyond administrative boundaries to include ‘ruralopilises’, – densely populated rural areas and outskirts not officially designated as cities. Today, ruralopilises are estimated to make upto 60 percent of urban Pakistan.⁶

Such urbanization without an accompanying shift in economic patterns does not bode well and as cities expand without planning, challenges of providing effective infrastructure and transportation and of delivering services continue to mount.

Creating Jobs

The State Bank has estimated that Pakistan needs at least a 6.6 percent growth rate to create 1.3 million jobs to cater to the new entrants into the market. By FY15 Pakistan had four million unemployed youth (aged 15-24 years), expected to rise to 8.6 million by 2020.⁷

The challenge is not just about creating more jobs. Cities have to produce employment opportunities that would make migrants relatively more productive. When available, jobs are usually of low quality, especially in manufacturing and services. Around 25 percent of young workers are in unstable, low-paid jobs without any benefits, while 35 percent work as unpaid family workers, majority of them women.⁸

Pakistan also has among the lowest levels of labour productivity in the developing world. According to World Bank, labour productivity in the 1980s grew by 4.2 percent every year, but the rate fell to 1.8 percent by the 1990s and to an average of 1.3 percent during 2000-2015. Since 2007, it has been growing at just 1 percent. A key factor inhibiting labour productivity remains the low accumulation of human capital. Of the 1.7 million entering the job market each year, only 1.3 percent have vocational training. The ability of individuals to participate in the labour force is further constrained by poor health. Close to 44 percent of children under five have stunted growth.⁹

Sectoral Focus

Encourage Manufacturing

The movement of people is determined largely by the type of jobs and where they are created. Transforming the quality and quantity of jobs will require an expansion of manufacturing, especially in the value-added segment, since every job in manufacturing creates 2.2 jobs in other sectors.⁰ Hence, manufacturing remains key to reviving the economy. However, Pakistan’s value-added manufacturing as a proportion of GDP decreased by 2016 to 12.8 percent, from 18.6 percent in 2005. Manufacturing can be encouraged by pushing industries and businesses that are export-oriented, or have considerable export potential, require little capital and are labour intensive, use relatively less energy and are densely populated by Small Medium Enterprises (SMEs).

Promote SMEs

Evidence shows that economies with strong SMEs are progressive and experience robust economic growth. According to the Small and Medium Enterprises Development Authority (SMEDA), 90 percent of all enterprises in Pakistan are currently SMEs, employing around 80 percent of all non-agriculture workforce. The share of SMEs in GDP is approximately 40 percent and they contribute almost 25 percent to total export earnings. The SME sector, thus, has the potential to absorb a large and growing workforce. Yet, SMEDA’s budget spending amounts to just 1 cent per capita compared to 9 cents per capita in India, 53 cents in Turkey and USD 1.92 in Thailand.

Pakistan must invest in modern skills for its workforce in areas like start-ups, innovation and digitalisation that are now a major focus for sustainable economic development elsewhere in the world such as Sweden. Plans to strengthen SMEs should also include easing access to credit, improving access to market, simplifying business registration and adopting a national SME policy.

Boosting the Housing Sector

The State Bank of Pakistan has estimated that across all major cities, urban housing was approximately 4.4 million units short of demand in 2015. Construction of an additional 100,000 houses each year can lead to both growth and employment opportunities.⁴ Housing and real estate sectors are directly linked to about 42 construction materials’ industries, creating jobs at much higher rates.⁵ While easing housing pressure on cities, investing in lowcost housing may also boost SME business in Pakistan.⁶

Making Pakistan an Urban Industrial Country

Provinces have not yet designed industrial policies that look at land usage and development of new cities, even though industrial investments under the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) have already begun. The Planning Commission has confirmed that nine industrial parks that will act as primary hubs of industrial activity in the country, are included in the CPEC framework to be built across four provinces.

Special economic zones can provide enormous opportunity for boosting employment and job creation. If these projects are launched in the vicinity of densely populated areas and urban centres, they can make a win-win scenario for the community and the industry. In such a case, these projects can also develop close integration with the local industry. These projects can further result in urban knowledge spill-overs to help develop a knowledge-based economy.

Punjab is currently identifying areas with the best potential to develop into cities and industrial estates, other provinces need to follow suit to economically align to CPEC. However, outdated land use regulation and building codes, the absence of a unified land record system and patchy data on land use continues to lead to poor urban land management.

Investing in Urban Transport for Integrating Labour Markets

A well-integrated urban public transport network contributes to economic growth by reducing transport costs and travel time, facilitating specialization of rms and workers, and decreasing the cost of economic transactions. However, Pakistan’s rapid urbanization is challenging the flimsy infrastructure of its cities, constraining economic activities and reducing potential of growth. Several transportation projects are being rolled out across cities without much understanding of their economic benefits or the local job market.

Researchers⁷ have worked on a series of three projects funded by the International Growth Center (IGC) to analyse the impact of urban transport on the labour market. These projects look at the effect of the Lahore Metrobus on employment by quantifying the causal impact of a reduction in transit cost and time due to investment in public transport infrastructure while measuring impact of mass transit on aspects of labour market integration. These projects found, a) introduction of the Metrobus in Lahore reduced time and cost of commuting for those already relying on public transport, b) substantial proportion of commuters switched to public transport, c) many commuters indicated they would use transport even if fare was increased substantially, d) commuters had higher average earning power than the population riding public buses in the past, and lastly, e) introduction of women’s-specic transport eases their integration into the labour market.

Some of the key policy messages emerging from this work suggest continued investment in, and expansion of high-quality public transport including mass transit, reduction in ticket subsidies and use of peak pricing to make mass transit financially sustainable. Pakistan’s transport sector must prepare for the rise in economic activity expected in urban centres following investments under CPEC. Introducing the right land-use policies and investing in low-cost public transport can help meet the likely increase in demand.

What can Governments do?

There are a few steps that the government can take to ensure cities are able to generate-instead of hamper-growth. Foremost is empowerment of city government in public service delivery and nancial matters and boosting local revenue generation. And last, but certainly not the least, providing a framework to guide urban planning and land-use.

A. Empowering Local Governments

The changing role of the government following devolution is impacting its ability to address urban challenges. The 18th amendment transferred scal and administrative powers for most federal subjects including urban planning, to the provinces, with further delegation to local governments. In fact, international experience shows urban development is best placed within the mandate of local governments.

However provincial authorities undermine the power of city governments to serve their residents. Provinces remain reluctant to empower local governments and have made exceptions in retaining large entities⁸ under their own control. Thus, local governments have a limited role in resolving issues such as the urban housing crisis and provinces continue to assume many responsibilities related to municipal controls, regulations and management. City governments also lack resources to fund schemes and are unable to borrow independently from international donors.

B. Empower Cities to Tax

Most urban taxes are implemented by each of Pakistan’s four provincial governments. These provincial governments have large jurisdictions, with populations ranging from 12 million to over 110 million. As managing cities is not the central function of these governments, most of them have not developed effective urban administration mechanisms.

Land and physical properties are a major source of untapped revenue for most developing countries cities’ .⁹ Punjab, for example, despite being home to nine cities with over a million people, collects about 6 percent of its total tax revenue, from property taxes.⁰ Other parts of Pakistan have not fared better. Sindh, which is home to Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city, has not had a revaluation of land and property since 2001. Yet, there is large potential to increase this. For example, an estimate from 2011 shows that Punjab could raise PKR 25 billion in property taxes if it undertook comprehensive reforms.

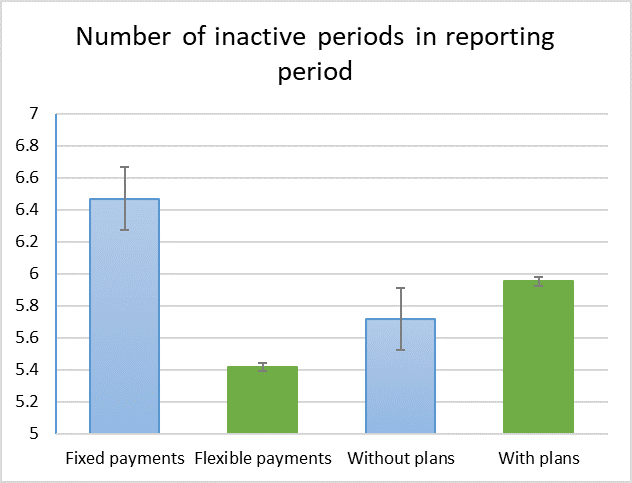

Taking the case of the urban property tax collection in Pakistan, researchers tested performance-based systems that consider both effort (i.e., incentivise the bureaucrat to exert the desired level of effort) and information revelation (i.e., creating the right incentives for the civil servant to truthfully disclose information to the state) dimensions. The objective of these studies was to increase tax collection. The completed studies found that performance incentives worked-tax revenues in circles where tax collectors were assigned to performance pay schemes had a 46 percent higher rate of growth. Moreover, easy to understand, transparent, ex ante, and objective incentive schemes were most effective-where tax collectors were paid a bonus directly tied to the revenue they collected above predefined benchmarks, they had a 62 percent higher growth rate in total revenue.

C. Improve City Planning

Given Pakistan’s growing population, which exerts extreme pressure on land, and dearth of nancially attractive investment opportunities, land is the most prized asset in terms of returns. This is complemented by a weak legal and administrative governance structure, which has contributed to an acute housing shortage, and cardependent sprawl.

A policy mandate to manage urbanization has been slow to emerge at the federal and provincial levels. Master plans for urban centres are usually devised to translate the city’s vision and economic goals, amongst other aspects, into tangible development and infrastructure strategies and projects. Unfortunately, in Pakistan, no comprehensive urban planning framework exists. At present, out of 150 towns and cities in Punjab, ten have crossed the one million population benchmark and only a few have updated and practical plans.

To facilitate urban planning and land management, experts are collating new data and reformatting existing data to inform policy. The focus is on spatial mapping and understanding urban economies-both of which are key for effective urban planning. A recent example is the World Bank’s report⁴ on urban agglomeration and spatial mapping, in which for the rst time in 2015, night lights data was used to measure economic growth for South Asian cities over the last ten years. Punjab is also now about to launch its urban spatial strategy.

Hina Shaikh is a Development Expert and is currently working with the Pakistan Team, International Growth Centre

This post originally appeared in UNDP’s Development Advocate Pakistan report focusing on Sustainable Urbanisation, Volume 5, Issue 4

References:

1. Pakistan’s urban population growth has been 3.2 percent whereas the regional average was 2.6 percent as per United Nations Population Division of the UN Department for Social and Economic Affairs’ comprehensive report titled “2018 Revision of World Urbanisation Prospects”

2. With Quetta, Lahore and Faisalabad showing the largest percentage increase in population.

3. United Nations Development Programme (2017), “Pakistan National Human Development Report 2017.” Available at http://www.pk.undp.org/content/dam/pakistan/docs/HDR/PK-NHDR.pdf

4. Ibid

5. Ministry of Climate Change and UNHabitat (2018), “The State of Pakistani Cities 2018.”Report on the State of Pakistani Cities (SPC) launched by the Ministry of Climate Change with technical assistance of the United Nations Human Settlements Program (UN Habitat)

6. Business Recorder, Dr. Haz A. Pasha, “The urban-rural divide.” Available at https://epaper.brecorder.com/2018/02/21/18-page/700950-news.html

7. World Bank (2014), “Pakistan Urban Sector Assessment: Leveraging the Growth Dividend from the Urbanization Process.”

8. Launching ceremony of the “State of Pakistani Cities” report launched by the Ministry of Climate Change with technical assistance of the United Nations Human Settlements Program (UN Habitat). Available at http://unhabitat.org.pk/?p=188

9. World Bank (2015), “Leveraging Urbanization in South Asia: Managing Spatial Transformation for Prosperity and Liveability.”

10. In 2018, 23.90 percent in industry and 34.82 percent in the service sector (world bank indicators)

11. Supra 6

12. Supra 6

13. United Nations, “2018 Revision of World Urbanization Prospects.” Available at https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/2018-revision-of-world-urbanizationprospects.html

14. Ernesto Sánchez-Triana, Dan Biller, Ijaz Nabi, Leonard Ortolano, Ghazal Dezfuli, Javaid Afzal & Santiago Enriquez, “Revitalizing Industrial Growth in Pakistan: Trade, Infrastructure, and Environmental Performance.” Available at https://books.google.com.pk/books/about/Revitalizing_Industrial_Growth_in_Pakist.html?id=2EgtBAAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&redir_esc=y#v=o nepage&q&f=false

15. Ishrat Hussain, “Messy and Hidden Urbanization.” Available at https://ishrathusain.iba.edu.pk/speeches/MessyandHiddenUrbanization.pdf

16. Ijaz Nabi and Hina Shaikh (2017), “The six biggest challenges facing Pakistan’s urban future.” Available at https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2017/02/15/the-six-biggestchallenges-facing-pakistans-urban-future/

17. Hina Shaikh, “Young blood: Pakistan’s bulging youth population needs employment opportunities.” Available at https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2018/02/09/young-bloodpakistans-bulging-youth-population-needs-employment-opportunities/

18. Supra 3 19. Pakistan Today (2019), “Over 44 percent children in Pakistan suffering from chronic malnutrition.” Available at https://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2019/03/08/over-44-childrenin-pakistan-suffering-from-chronic-malnutrition/

19. Pakistan Today (2019), “Over 44 percent children in Pakistan suffering from chronic malnutrition.” Available at https://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2019/03/08/over-44-childrenin-pakistan-suffering-from-chronic-malnutrition/

20. United Nations, “Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure: Why it Matters.” Available at https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/9_Why-itMatters_Goal-9_Industry_1p.pdf

21. Government of Pakistan, SMEDA, “State of SME’s in Pakistan.” Available at https://smeda.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=7:state-of-smes-inpakistan&catid=15

22. The ExpressTribune (2018), “Pakistan needs to become urban industrial society.” Available at https://tribune.com.pk/story/1858885/1-pakistan-needs-become-urban-industrialsociety/

23. Supra 15

24. Karandaaz Pakistan (2018), “Enhancing Builder Finance in Pakistan.” Available at https://karandaaz.com.pk/media-center/news-events/new-study-highlights-massive-economicbenets-low-income-housing/

25. Ibid

26. If current trends continue, Pakistan’s ve largest cities will account for 78 percent of the total housing shortage by 2035.

27. From Duke, Urban Institute and Lahore University of Management Sciences.

28. Such as the Karachi Water and Sewerage Board, Sindh Building Control Authority, Lahore Development Authority (LDA), and Lahore Waste Management Committee.

29. Research conducted by the IGC’s ‘Cities that Work’ initiative.

30. DAWN (2018), “Punjab property tax collection remains far behind.” Available at https://www.dawn.com/news/1397466 27. From Duke, Urban Institute and Lahore University of Management Sciences.

31. International Growth Centre (2011), “Policy Brief: Reforming the Urban Property Tax in Pakistan’s Punjab.” Available at https://www.theigc.org/wpcontent/uploads/2014/09/Nabi-2011-Policy-Brief.pdf

32. Ibid

33. From Harvard, London School of Economics and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

34. World Bank, “Leveraging urbanization in South-Asia.” Available at http://www.worldbank.org/en/region/sar/publication/urbanization-south-asia-cities